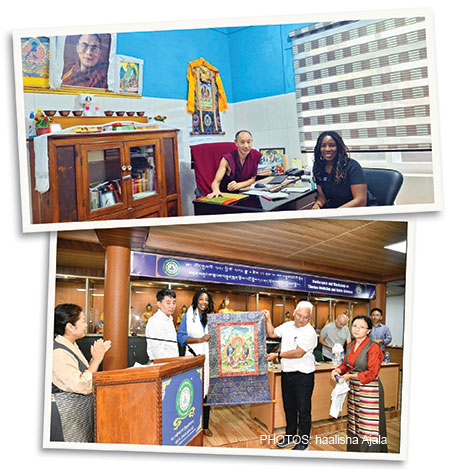

Dr. Ajala worked at the Tibetan School of Medicine in Dharamsala, India, where she shadowed the Dalai Lama’s personal physician

How do U.S. hospitalists find their way into international hospital medicine and global health care—and what have they learned on the journey? Several hospitalist leaders in global health care contacted for this article shared very different paths to their international connections. They said it’s important to enjoy working overseas, with all its challenges and its opportunities for personal fulfillment, while making meaningful contributions to the health care of other countries. But also, it’s essential to be clear on one’s motivations. Don’t expect to save the world.

For Khaalisha Ajala, MD, MBA, FHM, a hospitalist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, her father was born in Nigeria and she often traveled there when she was young. Her mother, a nurse, inspired her and her siblings to pursue medicine as a career. “I was born and raised in Baltimore, and saw that in this country, with such great resources, many people still struggle with chronic health issues and lower life expectancy.” Nigeria struggles in different ways with limitations in what its health care system can do for its people, she explained.

Dr. Ajala

“That experience of seeing the parallels for those who do not have access, whether in Nigeria or the U.S., made me want to do something about it.”

In 2013, Dr. Ajala created a nonprofit organization called A Tribe Called Health. “We work in urban communities in this country focusing on health education, with pop-up classes and panels and talks at high schools, helping those who may not have the access they should,” she said.

“Then I thought, well, if I’m doing that here, and I know there’s a need abroad because I’ve seen it in person, why can’t I just do the same thing somewhere else?” When she joined Emory after completing her medical training, Dr. Ajala realized that opportunities in global health didn’t require her to look very far.

She volunteered with Emory Health Against Human Trafficking, annually visiting a children’s orphanage in northern Thailand with Emory medical students. They provide health screenings for the children, many of whom might be considered stateless or at high risk for human trafficking.

She also volunteered with Emory’s Global Health Scholars Residency Program for residents and trainees in internal medicine who are on a global health track and want to work abroad. In the students’ third year they travel to Ethiopia for a month of inpatient work at Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa and to volunteer at its clinic. “I teach as medical faculty for the Emory residents and Ethiopian residents,” Dr. Ajala said. In addition to those regular visits to Ethiopia, she has also worked at Accra, Ghana; and at Dharamsala, India, home to Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama.

There is a history of colonialist attitudes by the developed world relative to the idea of global health care in lower-income and developing countries, Dr. Ajala noted. “Many of the practitioners in those countries understand this history, but they don’t hold any resentment. They look forward to partnering with those who care about caring for people all over the world.”

She said the way to build a global connection is to perceive it as a welcome partnership, not as Western doctors telling the locals how to do things. “Many of us can tell stories about what we’ve learned to do in another country, at a hospital that did not have all the resources we enjoy. I have been able to bring back to my U.S. hospitalist work some of their ideas.”

A path to pediatrics

Dr. Hickson

For Meredith R. Hickson, MD, MSc, assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at Michigan State University and partner in the pediatric hospital medicine group at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, both in Grand Rapids, her journey into global medicine began before medical school. She grew up in a Quaker community in Maryland, where she learned an expansive sense of personal responsibility for other human beings. Right out of college in 2011 she joined the Peace Corps.

“That had been a childhood dream of mine. I got posted to Senegal, where I worked on a public health project, training community health workers on topics like diet and nutrition. We lived in a village in a rural area. That experience is the reason I decided to pursue medicine, and pediatrics specifically,” she said.

Dr. Hickson’s medical school, the University of Michigan, is part of a global health consortium called the Fogarty International Center, run by the National Institutes of Health, with research partnerships in many different countries around the world. She spent a year working on a pediatric malaria research project in Uganda while rounding on the inpatient pediatric wards at the local community hospital that was hosting the study. “That was definitely a formative experience for me. The hospital doesn’t have a lot of resources, but the doctors I worked with were brilliant and exceptional clinicians.”

Dr. Hickson conducting malnutrition screenings in Uganda in 2018

In April of 2021, Dr. Hickson was accepted into a dedicated academic global health fellowship through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. That brought her to Botswana for three years, working half-time clinically at Princess Marina Hospital in the pediatric, neonatal, and ICU wards as well as pursuing research and teaching medical students.

Her partner, Cantor Rick Lawrence, was able to join her overseas, working as a chaplain at the hospital where she taught. “And then we had a child while we were over there. So, I had a whole life there, and that life came home with me when I returned to Michigan in April of this year.”

Overall, Dr. Hickson said, her fellowship in Botswana was an incredible learning experience. “I think the breadth of things I learned, how to manage a case, how to diagnose, is wider than it would have been if I hadn’t left the U.S. I got incredible hands-on training in managing patients with socioeconomic disparities or who came from different cultures,” she said. “That has helped me show compassion and empathy to patients who are recent arrivals to the U.S.”

Dr. Hickson’s current research is looking at how, with limited electronic monitoring and other techniques that hospitals in the U.S. take for granted, nurses in Botswana are able to take vital signs with a stopwatch, stethoscope, paper, and pencil, using a system first developed in Latin America. “Our research is aimed at helping nurses do that to monitor patients more carefully and then alert doctors when these kids are getting sicker before something serious happens. There have been changes in clinical outcomes, but staff tell me this intervention feels like it has made an incredible difference.”

She encourages other hospitalists interested in global medicine to look first at what their own university or institution has already developed, rather than trying to blaze new trails. “Always try to work within the frameworks that already exist, building on relationships that are already there.” Or, she adds, network with colleagues from other institutions or medical societies.

Not just health tourism

Global health is a broad concept, sometimes referred to as humanitarian health care. It includes work led by non-governmental organizations like Doctors without Borders. “Global health describes the work of physicians who come from higher-income countries to developing countries in order to volunteer and collaborate with others in those settings, with the goal of learning from each other but also improving health in the local community,” Dr. Ajala said.

International medicine can also mean taking a paying job in a hospital in another country. There’s a great need to educate doctors-in-training, and even a contingent of U.S. physicians who aim to fully relocate and practice careers in other countries, with credentialing to meet local standards.

Dr. Bodnar

Benjamin Bodnar, MD, a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, grew up in a family that did a lot of traveling, although more in familiar settings like Western Europe. “But I was always interested in branching out to the less familiar.”

As an undergraduate at Stanford University in California, he did a several-week volunteer placement at a children’s hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. “I learned quickly that a lot of international health opportunities, especially for students, are more what I would call health tourism. That caused me a lot of introspection, but it didn’t turn me off to the idea of global health.”

Between his third and fourth years of medical school at Columbia University, Dr. Bodnar took a year off to pursue medical research and got connected with the Earth Institute, which is a sustainable development academic institution associated with the Millennium Villages Project. That led him to spend a year in rural Ghana and Tanzania. “And that’s when I really learned what it was like to live and work in those environments.” He found it a fascinating, positive experience but also a difficult one, living in the bush in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Dr. Bodnar introducing his son, James, to the “neighbors,” (circa 2016) when he worked with Partners in Health in northeastern Rwanda

Dr. Bodnar’s combined med-peds residency was at Yale New Haven Hospital, which has an established global healthcare program called Johnson & Johnson Clinical Scholars, with well-established bidirectional exchanges in a number of sites in developing nations. That landed him at their site in Kampala, Uganda, where he came to recognize his fascination with medical quality improvement.

Today he works part-time as a med/peds hospitalist but also pursues a portfolio of research in quality and safety, which he directs for the adult hospitalist division at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. In his Ugandan work experiences, “I learned a lot, and also saw how many things were dysfunctional in its health care system.”

One of his mentors at Yale recognized his interest and encouraged him to consider specializing in medical quality improvement in developing and resource-limited countries as a career path. “It is true that the way we do things in the West is not always right. Physiology is the same, so medicine at the core is the same. But what you realize doing global hospital medicine is how, for many of the things we do in a resource-rich environment, we never think about them as optional, just expected and assumed.”

Going into environments where the lack of resources doesn’t permit that approach offers a perspective on what is a privilege versus a right and habit versus necessity, he said. “I think people who have experience in global medicine often have a more flexible mindset about problem-solving and risk tolerance.”

For two years starting in 2014, Dr. Bodnar and his wife, Alia, who is a primary care and addiction medicine physician, worked together in Rwanda with the non-profit Partners in Health, founded by the inspirational infectious disease doctor, Paul Farmer, while holding part-time appointments as hospitalists at Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. They would pile up intensive night shifts in Boston to make it possible to go back overseas.

“After we had babies, we came back and settled in Baltimore. But since I’ve been back, I’ve tried to maintain my international portfolio with the same partners I’ve worked with in Uganda for the past 12 or 13 years.” Their son lived with them in Rwanda for four months when he was four months old, but in the end, the family’s back-and-forth travel from the U.S. to Africa wasn’t sustainable for them.

Global special interest

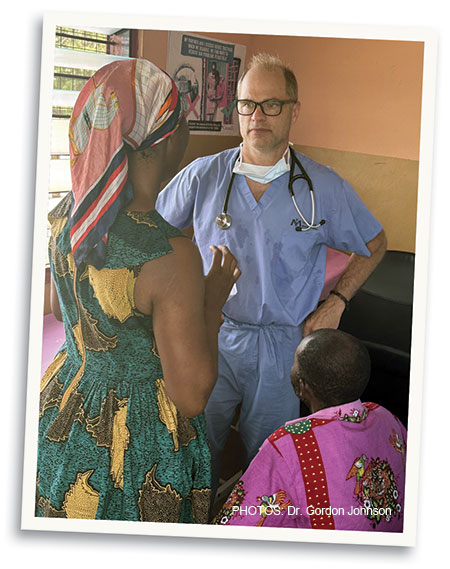

Dr. Johnson teaches point-of-care ultrasound at the University of Ghana

SHM’s Global Hospital Medicine Special Interest Group (SIG) has some 250 members. It was formed in 2021 by combining the Global Health and Human Rights SIG with the International Medicine SIG. It hosts hospitalists from other countries who visit the U.S., tries to promote bi-directional partnerships between countries, and presents forums at SHM conferences.

“We want to encourage people to have these experiences and learn about the world, but also try to be sensitive to not have this be medical colonialism,” Dr. Ajala said. “We need to normalize the idea of shared partnerships, not charity care. We should be learning from each other.”

Dr. Johnson

Gordon Johnson, MD, a hospitalist at Legacy Health in Portland, Ore., said he was always interested in global health, spending six months of his medical training in Delhi, India. Along the way, he developed a deep interest in point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) and especially its applications in resource-limited settings where there may not be access to more intensive scanning technologies.

“You can really see its benefit in developing countries,” he said. “Fortunately, POCUS devices have become much cheaper.” Now he hosts personal fund-raising rooftop parties for his friends and colleagues to raise enough money to purchase a POCUS wand that he can leave behind when he returns from his international trips.

Dr. Johnson provides medical consultations in Ghana

Currently, Dr. Johnson works 80% as an academic hospitalist at Legacy Health, leaving 20% of his schedule for global and humanitarian work. He has partnered with Isaac Armstrong, a tech professional from Portland who founded the Rural Health Foundation to support healthcare development in his native Ghana. Dr. Johnson, its medical director, goes there regularly to teach POCUS—to share Western medical techniques at the grassroots level with villages in Ghana. He typically spends about six to eight weeks a year in global health postings.

“Like a lot of hospitalists, I can work really hard, take a lot of shifts, and then take longer periods off, which I can use to come to Ghana and other places. Some of the work I do virtually.” Hospitalists have a gift with their specialty in that they can visit many countries and find local health providers with whom to work.

“Really, the most effect we have as foreign doctors is not coming in, seeing patients, and then flying home. It’s teaching our skills to the local physicians, giving them the support they need, and then getting out of their way and letting them do the work,” Dr. Johnson said.

A magical experience

Dr. Johnson said his family wasn’t always pleased about how much time he spends overseas. “I understand; when I’m taking all my free time and going to places that aren’t exactly tourist destinations. When I was allowed to, I would bring my kids with me and try to get them involved. I think they would say those were good experiences for them, as well.”

But he advised hospitalists interested in international experiences to try to do some of that exploring before they have children, even though it is possible to bring them on international adventures. His international work has also brought him to Norway, Thailand, Haiti, South Sudan, and Uganda.

Dr. Johnson emphasized not taking unappealing assignments. “When you volunteer, do it in a place you’d like to go. I’ve certainly been in war-torn areas and deserts and places with strict curfews, and that’s important work. But you don’t have to do that or apologize for going someplace where you’d rather be,” he explained.

“I want to be clear. I do this work because I love it. I don’t think I’m going to change the world or anything. But I’d much rather do this work than go sit on a beach somewhere. Sometimes you go on vacation and find that you’ve only spoken to waiters,” he said.

In Ghana, where he was stationed when The Hospitalist caught up with him, he said he feels like he’s working in partnership with the local doctors. “They sometimes say, ‘Hey, Gordy, we’d like to take you out for music tonight.’ You learn a lot about the culture, and the next thing you know, you’re having dinner with somebody’s grandmother or learning to cook Ghanaian food out in a village with your friend’s mom. I mean, the experience is magical!”

Larry Beresford is an Oakland, Calif.-based freelance medical journalist, and long-time contributor to The Hospitalist.