“This is something we’re going to see more frequently, and many of us already have,” Theresa E. Vettese, MD, said at HM20 Virtual, hosted by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The drastic drop in prescriptions for opioid pain medications in the last several years hasn’t curtailed the current opioid epidemic. Instead, the epidemic has to a great extent morphed into expanded use of illicit heroin and fentanyl, noted Dr. Vettese, an internist, hospitalist, and palliative care physician at Emory University and Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta.

Mythbusting

Treatment of acute pain in hospitalized patients on opioid agonist therapy for opioid use disorder (OUD) is actually pretty straightforward once a few common myths have been dispelled, she said.

One of these myths –common among both physicians and patients in treatment for OUD – is that prescribing opioids for management of acute pain will place such patients at risk for OUD relapse.

“In fact, the data really strongly suggest this is not the case,” Dr. Vettese said. “It will not worsen addiction. But if we don’t aggressively treat these patients’ acute pain, it puts them at higher risk for bad outcomes.”

Another myth – this one not uncommon among hospital pharmacy departments – is that only physicians with a special certification can prescribe methadone for inpatients.

“The federal laws are clear: Any physician who has a DEA license can prescribe methadone in the hospital acute care setting, not only for pain management, but also for treatment of opioid withdrawal. You can’t prescribe it in the outpatient setting for opioid withdrawal – that has to be dispensed through a federally regulated methadone outpatient treatment program. But in the hospital, we can feel safe that we can do so. You may need to educate your pharmacist about this,” she said.

Hospitalists also can prescribe buprenorphine in the acute care inpatient setting, both for pain and treatment of opioid withdrawal, without need for a DEA waiver.

“It’s useful to get some skills in using buprenorphine in the inpatient setting. You don’t need an X waiver, but I encourage everyone to do the X-waiver training because it’s a terrific educational session. It’s 8 hours for physicians and well worth it,” Dr. Vettese noted.

By federal law the inpatient physician also can prescribe 3 days of buprenorphine at discharge to get the patient to an outpatient provider.

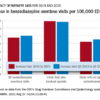

Misconceptions also abound about NSAIDs as a nonopioid component of acute pain management in hospitalized patients. They actually are extremely effective for the treatment of musculoskeletal, orthopedic, procedural, migraine, and some types of cancer pain. The number needed to treat (NNT) for postoperative pain relief for ibuprofen or celecoxib is 2.5, and when used in conjunction with acetaminophen at 325 mg every 4 hours, that NNT drops to 1.5, similar to the NNT of 1.7 for oxycodone at 15 mg. It should be noted, however, that the bar defining effective pain relief in randomized studies is set rather low: A 50% greater reduction in pain than achieved with placebo.

Many hospitalists would like to use NSAIDs more often, but they’re leery of the associated risks of GI bleeding, ischemic cardiovascular events, and worsening kidney function. Dr. Vettese offered several risk-mitigation strategies to increase the use of NSAIDs as opioid-sparing agents for acute pain management.

She has changed her own clinical practice with regard to using NSAIDs in patients with chronic kidney disease in response to a 2019 systematic review by investigators at the University of Ottawa.

“This was a game changer for me because in this review, low-dose NSAIDs were safe in that they didn’t significantly increase the risk of worsening kidney failure even in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease. So this has expanded my use of NSAIDs in this population through stage 3 CKD. With a creatinine clearance below 30, however, kidney failure worsened rapidly, so I don’t do it in patients with CKD stage 4,” Dr. Vettese said.

Gastroenterologists categorize patients as being at high risk of GI bleeding related to NSAID use if they have a history of a complicated ulcer or they have at least three of the following risk factors: Age above 65 years, history of an uncomplicated ulcer, being on high-dose NSAID therapy, or concurrent use of aspirin, glucocorticoids, or anticoagulants. Patients are considered at moderate risk if they have one or two of the risk factors, and low risk if they have none. Dr. Vettese said that, while NSAIDs clearly should be avoided in the high-risk group, moderate-risk patients are a different matter.

“Many avoid the use of NSAIDs with moderate risk, but I think we can expand their use if we use the right NSAID and we use protective strategies,” Dr. Vettese said.

Celecoxib is the safest drug in terms of upper GI bleeding risk, but ibuprofen is close. They are associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk of bleeding when compared with risk in patients not on an NSAID. Naproxen or indeomethacin use carries a fourfold to fivefold increased risk.

“Celecoxib with a proton pump inhibitor is safest, followed by celecoxib alone, followed by ibuprofen with a proton pump inhibitor. So I advocate using NSAIDs more frequently in people who are at moderate risk by using them with a PPI,” she said.

There is persuasive evidence of increased cardiovascular risk in association with even short-duration NSAIDs, as the drugs are utilized in the treatment of acute pain in hospitalized patients. That being said, Dr. Vettese believes hospitalists can use these drugs safely in more patients by following a thoughtful cardiovascular risk-mitigation strategy developed by Italian investigators.

© Frontline Medical Communications 2018-2021. Reprinted with permission, all rights reserved.