The Case

A healthy 42-year-old woman presents to the hospital with acute-onset pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath. She has not had any recent surgeries, takes no medications, and is very active. A lung ventilation-perfusion scan reveals a high probability of pulmonary embolism (PE). The patient’s history is notable for two second-trimester pregnancy losses. The patient is started on low-molecular heparin and warfarin (LMHW).

Should this patient be tested for thrombophilia?

Background

Thrombophilia can now be identified in more than half of all patients presenting with VTE, and testing for underlying causes of thrombophilia has become widespread.1 Physicians believe that thrombophilia testing frequently changes management of patients with VTE.2

Thrombophilias can be classified into three major categories: deficiency of natural inhibitors of coagulation, abnormal function or elevated level of coagulation factors, and acquired thrombophilias (see Table 1).

The prevalence of specific thrombophilias varies widely. For example, the prevalence of activated protein C resistance (the factor V Leiden mutation) is 3% to 7%. In comparison, the prevalence of antithrombin deficiency is estimated at 0.02%. Each thrombophilia is associated with an increased VTE risk, but the level of risk associated with a given thrombophilia varies greatly.1

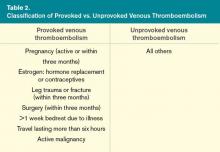

Before testing for thrombophilia in acute VTE, assess the risk of recurrent VTE by determining if the thrombosis was provoked or unprovoked. A VTE event is considered provoked if it occurs in the setting of pregnancy within the previous three months; estrogen therapy; immobility from acute illness for more than one week; travel lasting for more than six hours; leg trauma, fracture, or surgery within the previous three months; or active malignancy (see Table 2,).3 Unprovoked VTE has a recurrence rate of 7.4% per patient year, compared with 3.3% per patient year for a provoked VTE; the risk is even lower (0.7% per patient year) if the risk factor for the provoked VTE was surgical.4

Testing for thrombophilia is indicated if the results would add significant prognostic information beyond the clinical history, or if it would change patient management—in particular, the intensity or the duration of anticoagulation.