Teaching Cases: A Recipe for Success

Clinician educators can nurture learners within the evolving clinical environment

A chef is a skilled professional cook.1 In many ways, hospitalist clinician-educators are like chefs, seeking to prepare and deliver an educational experience that nourishes and satiates the learner. However, modern inpatient care—with its capacity challenges, the recent COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing staffing shortages—makes this challenging.

Early in the pandemic medical students left the clinical environment, and they did not care for patients with COVID-19 upon returning.2 Hospital epidemiology changed, with fewer “bread and butter” conditions and reduced resources for treating non-COVID-19 illnesses.3 These challenges modified our learners’ clinical experiences to mirror take-out dining: the incorporation of technology to increase safety and compressed timeframes for rounds and rotations.4 While the COVID-19 pandemic has abated somewhat from the hospital, these challenges remain.

Even before COVID-19, the unpredictability and idiosyncrasy of the clinical environment made curating effective, high-quality educational experiences challenging.5 At times, financial pressures for hospital systems drive quality metrics and push against education in favor of service. Many patients are in the hospital awaiting post-acute placement without active problems to diagnose or manage, and time at the bedside for clinicians continues to be the minority of each day.6 Does today’s teaching menu for hospitalists still consist of teachable moments, or should we be satisfied with a fast-food, drive-thru experience?

We offer this perspective: all cases are good teaching cases. Just as a great chef can make a wonderful meal with seasonal ingredients alone, clinician educators can continue to nurture learners within the evolving clinical environment. All cases are good teaching cases when we recognize and understand context, focus on intentional learning, and ensure that the serving size matches learners’ needs.

Context matters

The clinical environment has a profound influence on the educational experience.7 Consider a restaurant: a loud or chaotic environment distracts from the gustatory experience. A chef must curate the space to allow their guests to fully experience the food. Similarly, the “noise” of the clinical learning environment requires the teacher to create time and space for effective learning. Great chefs adapt to different kitchens, tools, and time schedules. Similarly, clinician educators must constantly adapt to a changing care environment.

A recipe makes learning intentional

There is substantial focus at the curricular and programmatic levels of medical education on developing high-quality learning objectives. Clinical teachers may find setting objectives challenging because of an ever-changing patient census. How do you plan a menu when you don’t know what ingredients will be available? Learning objectives can be developed intentionally and collaboratively in the moment between teachers and learners. Teachers and learners should seek to develop learning goals at the beginning of their time together and continue creating more specific learning plans based on the cases available. The combination of learners, patients, and learning environment helps guide learning objectives for each patient case.

For example, a typical case of cellulitis becomes more engaging when one considers changes to clinical variables: “What if this rash was bilateral?” “Should we obtain a lower extremity ultrasound?” “Are blood cultures necessary?”

Noting the educational needs of different learners may offer insights into areas of teaching focus. Does a student want to focus on physical exam skills, while a senior resident wants to improve knowledge on core medicine topics? Perhaps we charge the senior resident to consult the primary literature while we do exam rounds with the student, circling back later to review what the senior has learned. We must adapt our recipe to the ingredients at hand.

Serving up the right amount of learning

In addition to combining ingredients to bring out the best flavors, a chef must also serve the right amount of food. If the portions are too small patrons may feel that they didn’t get their money’s worth, and if the portions are too large they may be too full to enjoy the meal and order dessert. Cognitive load theory suggests that our learners come to the clinical learning environment with different learning appetites and abilities to digest teaching each day.8 If the teacher serves up more than the learner can digest, well-intentioned efforts may end up being resented. Conversely, if the teacher trades education for efficiency, irreplaceable learning opportunities are lost.

Elements of a good teaching case

When we consider context, recipe, and portion size in crafting a learning experience, we have the opportunity to cook up something special. Let’s consider two recipes for a good teaching case.

Recipe #1, Med Ed Soup

Ingredients:

- Patient

- Learner

- Teacher

Instructions: Mix and serve.

- Modifying the ingredients or their proportion will still create an educational soup.

- Alternatively, clinician educators and learners may desire a more nuanced recipe for a good teaching case, one that considers learning and the environment more intentionally. Such a recipe yields a coveted educational pastry:

Recipe #2, Med Ed Pastry

Ingredients:

- Patient-specific factors—the care team must be able to obtain history directly from the patient, or from others about the patient. Obtaining history is not the same as being able to verbally communicate directly with the patient.

- Learner-specific factors—the learner must establish and communicate specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely (SMART) objective(s) for the patient encounter.9 If the learner is unable to do so, consider referencing program or clinical-rotation objectives, or using published recommendations, such as those for the curriculum of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine.10 Teachers can also collaborate with learners to create an overarching educational goal and set specific learning objectives to focus teaching.

- Teacher-specific factors—the teacher must have a fundamental core knowledge of internal medicine. If another learner is serving as the teacher, they must have a fundamental core knowledge of the topic. The teacher must personalize and communicate the learning objectives for the patient encounter. A great teacher successfully juggles goals, such as role modeling effective clinical skills including professionalism, creating and maintaining a positive, safe learning climate, and promoting learner understanding and retention.11

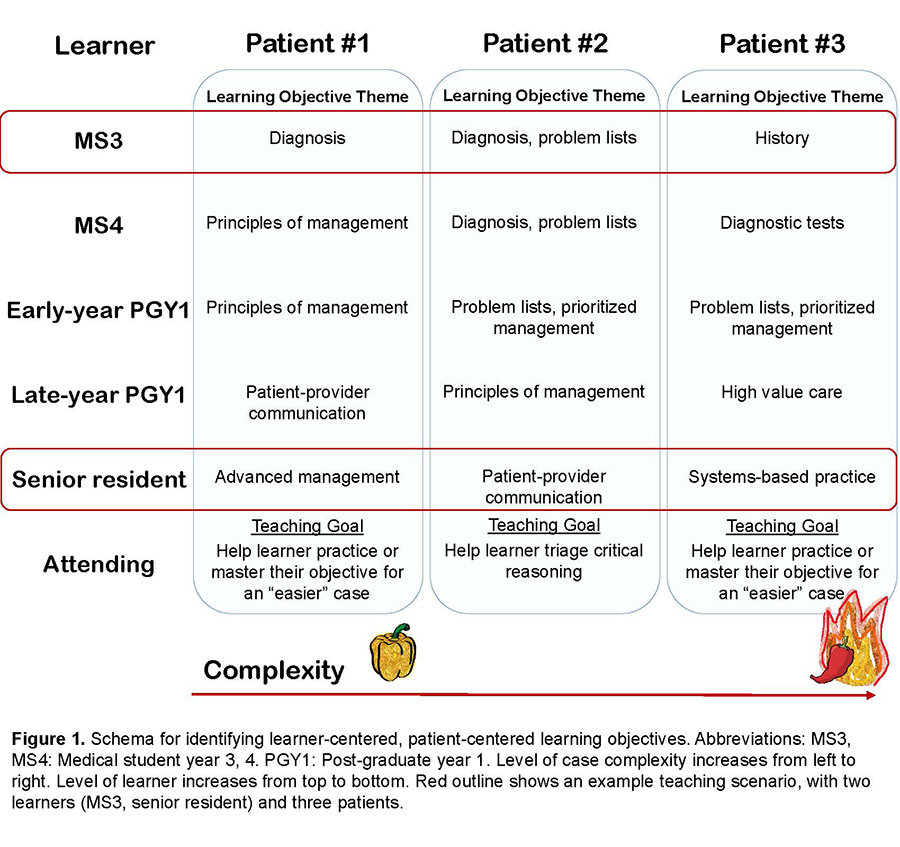

Instruction: Aligning patient, learner, and teacher-specific factors is key for successful learning. If case complexity and learner objectives are discordant and case availability is limited, the teacher should modify the learning objectives to better fit the given case. This process is –represented in the learner-patient matrix in Figure 1.

Elements in action

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a common diagnosis with increased incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic and learning opportunities for all levels.12 Consider a patient with alcohol use disorder presenting to the hospital five hours after their last drink with confusion, slurred speech, fingertip tremors, and elevated blood alcohol level. Recipe #1 for this case will certainly offer teaching, however, recipe #2 increases the potential for expanded learning across different levels (e.g., pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, health care systems) throughout the hospital course.

A teaching schema for our patient with AWS can be adapted to the learner-patient matrix in Figure 1. For the third-year medical student with a good foundation of basic science and strong history-taking skills, appropriate learning objectives include developing and sharing an illness script for AWS. A fourth-year student with strong presentations and problem representations could be challenged to identify potential complications (e.g., gastritis, hepatitis, refeeding syndrome, Wernicke’s encephalopathy) and to recommend interventions to prevent or mitigate them. An experienced intern or early senior resident who consistently prioritizes problem lists and differential diagnoses could be challenged to share the evidence behind AWS management and identify barriers to hospital discharge. By considering patient, learner, and teacher-specific factors along with case-specific learning objectives, we can expand the learning possibilities from a common diagnosis across different learner levels.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to change medical education. The educational paradigm must shift to recognize that every case is a good teaching case. There is a multitude of learning opportunities through diagnostic clues, therapeutic strategy, and systems-based practice that offer robust teachable moments with our patients.13 Rather than focus on finding a great case, we must strive to make every case great for teaching.

Bonne santé!

Key Points

- Consider learning environment changes as an opportunity to create an incredible and effective learning experience.

- Pause and plan. Think about what you are making when teaching and gather the ingredients.

- Identify and tailor learning objectives to the learner’s level.

Dr. Hoffman

Dr. Jagannath

Dr. Olson

Dr. Hofmann (@HeatherNHofmann ) is a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Loma Linda University Health, in Loma Linda, Calif. Dr. Jagannath (@AnandJag1) is a teaching hospitalist and site director for medical students at the VA Portland Healthcare System and an assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, VA Portland Healthcare System, Portland, Ore. Dr. Olson (@andrewolsonmd) is a hospitalist in the departments of medicine and pediatrics and an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minn., where he is the founding director of the division of hospital medicine within the department of medicine and the director of medical education research and innovation in the medical education outcomes center. Dr. Olson receives grant funding from the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Crico to study improving diagnosis, and from 3M unrelated to this work.

References

- Merriam Webster. Chef. Merriam-Webster Dictionary website. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/chef. Accessed July 30, 2023.

- Whelan A, et al. Guidance on medical students’ participation in direct patient contact activities. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/media/43311/download. Published March 17, 2020. Last updated August 14, 2020. Accessed July 30, 2023.

- Rosenbaum L. The untold toll—the pandemic’s effects on patients without COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2368-71.

- Hofmann H, et al. Virtual bedside teaching rounds with patients with COVID-19. Med Educ. 2020;54(10):959-60.

- Plesac M, Olson AP. See none, do none, teach none? The idiosyncratic nature of graduate medical education. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(4):255-6.

- Kara A, et al. A time motion study evaluating the impact of geographic cohorting of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):338-44.

- Olson APJ, et al. Teamwork in clinical reasoning – cooperative or parallel play? Diagnosis. 2020;7(3):307-12.

- Young JQ, et al. Cognitive load theory: implications for medical education: AMEE guide no. 86. Med Teach. 2014;36(5):371-84.

- Grote D. 3 Popular goal-setting techniques managers should avoid. Harvard Business Review website. https://hbr.org/2017/01/3-popular-goal-setting-techniques-managers-should-avoid. Published January 2, 2017. Accessed July 30, 2023.

- Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine. UME/GME program resources. AAIM website. https://www.im.org/resources/resources-program. Updated May 2023.

- Kost A, Chen FM. Socrates was not a pimp: Changing the paradigm of questioning in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(1):20-4.

- Sharma RA, et al. Alcohol withdrawal rates in hospitalized patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210422. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0422.

- Fitzgerald FT, Tierney LM. The bedside Sherlock Holmes. West J Med. 1982;137(2):169-75.