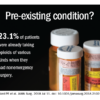

Nearly one-quarter of presurgery patients already using opioids

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. … Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

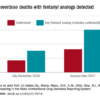

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).