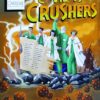

COVID-19 crushers: An appreciation of hospitalists

The hospitalist team at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics in Bellevue, Wash., has been a major partner of our Clinical Documentation Integrity Department in achieving its goal of accurately capturing the quality care patients receive on their records.

For many years, we have been witnesses of our hospitalists’ hard work, and the unique challenges of this pandemic further showed their tenacity and resilience. I thought that the best way to tell this story is through the poster accompanying this article.

To the viewer, this demonstrates the fierce battle raging between our hospitalists and the invisible foe, COVID-19. To my hospitalist colleagues, this is a constant reminder, albeit visually, that you are appreciated, admired and valued – not only by the CDI Department but by the whole organization as well.

Beyond my local colleagues, I would like to also thank the hospitalists working around the globe for their dedication and resolve in fighting this pandemic.

Mr. Valentin is a nurse and Certified Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialist at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics, Bellevue, Wash. His clinical specialties within nursing practice are in the OR, acute inpatient psychiatry, and the AIDS Unit.