Case

Dr. HM is a third-year internal medicine resident physician preparing to apply for a hospitalist position after completing residency. As an underrepresented physician in medicine, she seeks to join a hospitalist group that values inclusivity and diversity. She is particularly interested in learning about initiatives within the institution that foster a sense of belonging.

Brief overview of the issue

For decades, recruiting a diverse and inclusive workforce has been a priority across industries.1 Such teams drive innovation and creativity by uniting varied perspectives and problem-solving approaches, as well as fostering effective solutions.2,3 A culture of belonging and mutual respect further enhances collaboration, morale, and overall productivity.4 Diverse teams excel in decision-making by anticipating and addressing the needs of varied stakeholders, leading to more adaptable and sustainable strategies.5 Finally, diversity and inclusivity can enhance an organization’s reputation, attracting top talent and fostering a supportive, dynamic workplace culture.6

Healthcare institutions nationwide have implemented initiatives to promote diversity and inclusivity in the physician workforce in a myriad of ways, including within our institutions and sections of hospital medicine.7-9 Bringing diverse perspectives and experiences can lead to more culturally sensitive approaches to patient care and patient concordance, ultimately resulting in improved patient outcomes.10-12 Inclusivity also fosters a collaborative and innovative environment, as healthcare teams feel valued and empowered to contribute.2-3 A diverse workforce improves racial and ethnic concordance between the patient and clinician, which has been shown to improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.12-14 Finally, inclusive practices contribute to higher morale and job satisfaction, reducing burnout, and improving retention among healthcare professionals.15 Given our important role in healthcare, we believe that a diverse group and an inclusive environment are crucial to providing the best care to our patients and value to our institution.

Within the section of hospital medicine at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, we have a Justice-Equity-Diversity-Inclusivity (JEDI) Committee comprised of hospital medicine staff focused on promoting and achieving diversity in all respects to create a just, equitable, and inclusive working environment.9 Several of the JEDI committee members sought to improve the inclusive hiring practices of both our physicians and advanced practice practitioners (APPs) within our section of hospital medicine to increase the pool of diverse interviewees. Therefore, a partnership between the JEDI committee and the Recruitment Committee within the section of hospital medicine, the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (ODEI), and human resources at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist was formed to develop a process that would offer hospital medicine applicants an opportunity to meet with a representative from any of the system resource groups (SRGs), formerly known as “Affinity Groups.” The goal is to provide the applicant with an opportunity to meet with a current employee who would be able to share their perspective about our organization and the local community from their cultural background and experiences.

At our institution, SRGs are volunteer-led groups committed to embracing the diversity of staff, clinicians, providers, faculty, and learners, and to creating an environment of inclusion. They offer an opportunity for individuals with a common identity and experience to connect, to support workforce engagement and retention through mentorship efforts and professional development, and to represent our institution in our communities. They are open for all employees to participate, thereby advancing allyship and fostering intersectionality. SRGs support our institution’s mission and commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. We currently have the following SRGs at our institution and have plans to expand them throughout the larger Advocate Health Enterprise:

- Accessibility FOR ALL (A4A)

- African American Women Exemplifying Commitment to Equity and Leadership (A2 WeXcel)

- Asian Heritage and Allies (AHA)

- UNIDOS (Hispanic/Latinx)

- Indigenous People and Allies

- Shalom Jewish

- EQualityOne for LGBTQ+

- Muslim

- Veterans Society: One Team One Mission

- Atrium Health White Allies for Racial Equity

Creating a process to meet with an SRG representative

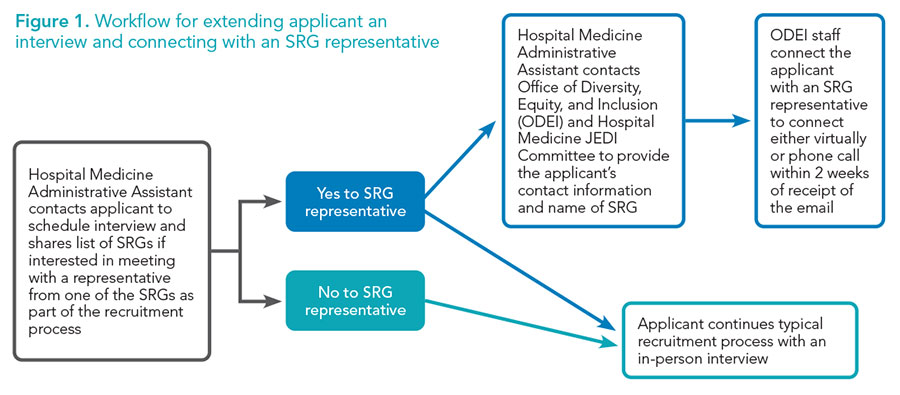

The first step was for the partners to establish a process to ensure applicants were informed of the various SRGs at our institution and to offer an opportunity to meet with an SRG representative. If the Hospital Medicine Recruitment Committee decides to extend an interview to an applicant, an administrative assistant from hospital medicine contacts the applicant via email to schedule an in-person interview. This email also includes details about SRGs and offers an option for the applicant to connect with one or more SRG representative(s) either virtually or by phone during the recruitment process. If an applicant declines to meet with an SRG representative, the applicant will then proceed with the standard recruitment process. It should be noted that connecting with an SRG representative during the recruitment process has no impact on an applicant’s eligibility for a position or interview. If an applicant wishes to connect with an SRG representative, then an administrative assistant from hospital medicine provides the ODEI staff and JEDI Committee member with the applicant’s contact information and the name of the SRG with whom they wish to speak. The ODEI staff then connects the applicant with the SRG representative via email. The SRG representative is expected to meet virtually or over the phone with the applicant within two weeks of the connection email being sent out (Figure 1).

The first step was for the partners to establish a process to ensure applicants were informed of the various SRGs at our institution and to offer an opportunity to meet with an SRG representative. If the Hospital Medicine Recruitment Committee decides to extend an interview to an applicant, an administrative assistant from hospital medicine contacts the applicant via email to schedule an in-person interview. This email also includes details about SRGs and offers an option for the applicant to connect with one or more SRG representative(s) either virtually or by phone during the recruitment process. If an applicant declines to meet with an SRG representative, the applicant will then proceed with the standard recruitment process. It should be noted that connecting with an SRG representative during the recruitment process has no impact on an applicant’s eligibility for a position or interview. If an applicant wishes to connect with an SRG representative, then an administrative assistant from hospital medicine provides the ODEI staff and JEDI Committee member with the applicant’s contact information and the name of the SRG with whom they wish to speak. The ODEI staff then connects the applicant with the SRG representative via email. The SRG representative is expected to meet virtually or over the phone with the applicant within two weeks of the connection email being sent out (Figure 1).

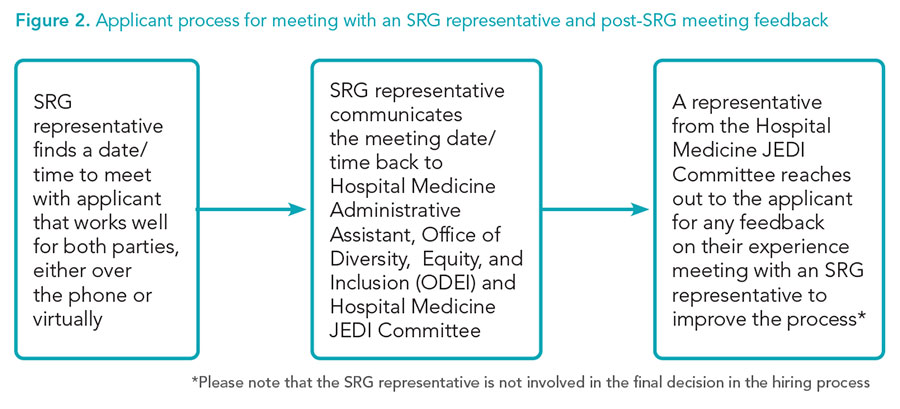

Once the meeting date and time have been arranged, the SRG representative communicates back to the Hospital Medicine JEDI Committee, the ODEI, and one of the administrative assistants from hospital medicine. Following the meeting, a JEDI Committee member contacts the applicant for feedback on their experience. It should also be noted that the SRG representative does not participate in the final hiring decision of the applicant (Figure 2).

Once the meeting date and time have been arranged, the SRG representative communicates back to the Hospital Medicine JEDI Committee, the ODEI, and one of the administrative assistants from hospital medicine. Following the meeting, a JEDI Committee member contacts the applicant for feedback on their experience. It should also be noted that the SRG representative does not participate in the final hiring decision of the applicant (Figure 2).

Outcomes and future directions

In our case, Dr. HM received an interview offer and was informed about the option to meet with an SRG representative. Dr. HM requested to connect with an SRG representative from A2 WeXcel during their recruitment process. A meeting date and time were arranged, and Dr. HM met with a representative from A2 WeXcel (Dr. WF) 10 days after the request. Dr. HM also had an interview with hospital medicine and was ultimately offered a position. Dr. HM’s post-SRG meeting comments were indicative that the meeting with the SRG representative was helpful during the recruitment process and vital to the inclusive hiring process:

“I had a great experience with Dr. WF during the recruitment process. She had reached out to me via email, making it easy to get in touch with her. She had a lot of availability in which to speak and offered different platforms, which was convenient. She was prompt in calling at our scheduled time, and we had a good conversation about the A2 WeXcel group and how it fits within the institution. It’s empowering to know as an applicant that there were groups such as these within the system. It shows the sense of community at this hospital and helps to envision yourself as a part of it. This played a major role in my decision to accept the hospitalist job position to work at the institution.”

Since the implementation of this process in July 2021, 60% of our hospital medicine physicians and APPs who met with an SRG representative went on to join our section of hospital medicine. Below are additional select comments from applicants who accepted an offer to join our section on hospital medicine:

“My meeting with the AHA representative was awesome! I enjoyed my time speaking with her. I believe the mission and the ideas she has for the SRG will have an enormous impact on the providers. We discussed various ideas and suggestions for the future that I felt were well received! Overall, I’m so glad I got to speak with her and learn not only about the JEDI and this SRG but also about all the other ones as well! This was a big reason I chose to come to this institution because it showed that inclusion is a priority.”

“I had a wonderful conversation with a representative from the Indigenous People and Allies SRG and am looking forward to being a part of the group once the meetings begin. I am hoping to learn more and, in turn, contribute from my side toward its growth. This truly influenced my decision to join this institution!”

As with any process, there were challenges noted that should be shared. First, since some of the SRG representatives are clinicians, they often had to meet outside regular hours, such as at nights or on weekends, to ensure the process continued smoothly. Second, there were a few instances where the SRG representative was not able to meet the applicant within the two-week window due to various circumstances that often related to coordinating a mutually convenient time. Despite these challenges, they were still able to meet even though it was not within that two-week timeframe.

For future directions of incorporating SRGs in the recruitment process, we plan to continue collaborating with ODEI and human resources to expand this program to other departments, sections, and markets within our health system.

If this program proves successful on a larger scale within the institution, we are considering implementing “open house” dates for each SRG. This approach would allow applicants to meet with SRGs collectively, reducing the time commitment for SRG representatives by minimizing the need for individual meetings with each applicant. Additionally, future expansion efforts will incorporate feedback on both the applicants and SRG representatives to improve the process and ensure the applicant remains connected and engaged with their SRG once hired. Providing orientation and training for SRG representatives and ensuring they have the capacity to participate effectively as the program expands will also be crucial.

Bottom line

Creating a diverse workforce in hospital medicine is imperative, and it starts with inclusivity in the hiring process. The integration of SRGs in the hiring process within our Section of Hospital Medicine at our institution has enhanced diversity and inclusivity, providing candidates with a welcoming community that positively influences recruitment and retention outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to Donna Averitt, Michael Ginsberg, Elizabeth Glover, Peggy Harris, Jakki Opollo, and Julee Rose for their contributions. Without their support and dedication, this process would not have been possible.

Dr. Lippert

Ms. Haller

Dr. Snipe

Ms. Lane-Brown

Ms. Bolick

Dr. Nagaraj

Dr. Lippert is an adult hospitalist at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, a former member of the JEDI Committee in the section of hospital medicine, an assistant professor of internal medicine, and an associate program director for the Wake Forest University School of Medicine internal medicine residency program in Winston-Salem, N.C. Ms. Haller is a hospitalist at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist. She established the section of hospital medicine Wellness Committee and leads the Atrium Health Hospital Medicine Justice-Equity-Diversity-Inclusivity (JEDI) Committee in Winston-Salem, N.C. Dr. Snipe is an adult hospitalist at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, co-leader for the Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) Committee for the section of hospital medicine, and clinical assistant professor at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C. Ms. Lane-Brown is a manager/operations lead in the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist in Winston-Salem, N.C. Ms. Bolick is an administrative assistant in the section on hospital medicine at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist supporting the section chief for hospital medicine, the section APP for hospital medicine, the medical directors for Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, hospitalist at home, and the JEDI Committee in Winston-Salem, N.C. Dr. Nagaraj is a clinical associate professor of internal medicine at the Wake Forest School of Medicine, interim section chief of hospital medicine, and specialty medical director for hospital medicine at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist in Winston-Salem, N.C.

References

- Williams CL, et al. Corporate diversity programs and gender inequality in the oil and gas industry. Work Occup. 2014;41(4):440-76. doi: 10.1177/0730888414539172.

- Page SE. The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies (New Edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7sp9c.

- Hülsheger UR, et al. Team-level predictors of innovation at work: a comprehensive meta-analysis spanning three decades of research. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(5):1128-45. doi:10.1037/a0015978.

- Harte JK, et al. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(2), 268–79. doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268.

- Rock D, Grant H. Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review website. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter. Published November 4, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Diversity wins: how inclusion matters. McKinsey & Company website. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/diversity%20and%20inclusion/diversity%20wins%20how%20inclusion%20matters/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters-vf.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Rotenstein LS, et al. Addressing workforce diversity—a quality-improvement framework. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1083-6. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2032224.

- Khanijow K, Ofodu U. A roadmap for new DEI officers in hospital medicine programs. The Hospitalist website. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/37916/diversity-medicine/a-roadmap-for-new-dei-officers-in-hospital-medicine-programs/. Published October 1, 2024. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Justice-Equity-Diversity-Inclusion (JEDI) Committee. Wake Forest University School of Medicine website. https://school.wakehealth.edu/departments/internal-medicine/hospital-medicine/diversity-and-inclusion. Published June 2024. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Saha S, et al. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275-85. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4.

- Shen MJ, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-40. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4.

- Byas K. Racial concordance in healthcare can improve health outcomes and lower costs. The Center for Health Affairs Blog. https://www.neohospitals.org/healthcare-blog/2024/september/racial-concordance-in-healthcare-can-improve-health-outcomes-and-lower-costs. Published September 26, 2024. Accessed March 6, 2025.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003.

- Takeshita J, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583.

- West CP, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X.