Among their many responsibilities, hospitalists typically rank patient care as their number one priority and the education of medical students, residents, and fellows as a critical number two. As hospitalists have grown as a field, they have taken on increasing roles in educational activities, including leading medical student clerkships and residency fellowship programs, designing curricula, and participating in procedural training, coaching, and mentoring.1

Among their many responsibilities, hospitalists typically rank patient care as their number one priority and the education of medical students, residents, and fellows as a critical number two. As hospitalists have grown as a field, they have taken on increasing roles in educational activities, including leading medical student clerkships and residency fellowship programs, designing curricula, and participating in procedural training, coaching, and mentoring.1

Although patient care is the key focal point, the traditional structure of daily hospital rounds with a team over a longitudinal period provides opportunities for student observation, goal setting, feedback, and impressive student learning. Hospitalists can strategically intersperse teaching and more direct clinical care throughout the day, providing learners with opportunities for growth while still maintaining excellent clinical care.2

However, the challenges of direct patient care responsibilities and other required tasks may sometimes infringe upon an optimal medical education. Thus, practitioners must learn how to appropriately balance and prioritize competing demands on their time.

Based on their positions, hospitalists have greater or lesser educational responsibilities. Some community hospitalists may sometimes play supervisory roles for medical students, residents, or fellows without being direct members of a trainee service. Others may oversee teaching services, in which some combination of trainees with varying levels of experience work together to oversee care. In many cases, hospitalists also need to cover some additional patients not on the teaching service, which requires thoughtfulness in terms of timing and prioritization. Given the scope of these demands, it can be challenging to get everything done.

Dr. Smith

“Preparation and organization are both key for maintaining that balance between clinical care and teaching responsibilities,” said Dustin T. Smith, MD, SFHM, section chief for inpatient medicine at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, associate program director for the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program, and an associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Kathleen Lane, MD, director for the Inpatient Process of Care Clerkship and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, added, “I really appreciate the value of setting expectations, having structure, and trying to develop trust between the team and me.”

Kathleen Lane, MD, director for the Inpatient Process of Care Clerkship and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, added, “I really appreciate the value of setting expectations, having structure, and trying to develop trust between the team and me.”

Academic hospitalists have additional teaching responsibilities, such as mentorship and formal lectures for medical students, residents, or colleagues. Academic medicine also comes with additional responsibilities not directly related to either clinical care or education, such as administrative and research tasks, which may also be essential in advancing one’s career.

The Hospitalist talked with Drs. Smith, Lane, and other hospitalists about how they balance and prioritize clinical care and teaching while working directly with trainees on the wards. They also addressed some of the challenges of balancing clinical care, teaching, and other duties within the broader context of a career in academic hospital medicine.

Balancing clinical care and teaching on the wards

The optimal way to balance teaching while on the wards may vary somewhat depending on one’s specific appointment and responsibilities, individual organizational approach, personal style and preferences, and local institutional culture, but some general overarching principles may apply.

Creating a positive environment, getting to know your team, and setting expectations

Several of the hospitalists pointed out the importance of setting the right tone for the teaching team to help ensure a positive, collaborative approach essential for both trainee learning and optimal clinical care.

“I want to get to know them and show that I am invested in them as a human being, invested in them becoming an excellent physician,” said Dr. Lane. “When that is there, the team becomes more engaged in sharing their thoughts and ideas about patient care, even if it’s not their direct patient.”

Dr. Smith emphasized the importance of maintaining the right team atmosphere, one which emphasizes psychological safety and approachability, an environment in which asking questions and soliciting real-time feedback is welcomed. He added, “I want our healthcare professional trainees to know that we’re here on service working together as a team to try to provide excellent patient care—we need one another to succeed at this.”

An important part of getting to know the team is getting a sense of trainees’ skill levels and strengths, to help inform the degree of supervision and the kind of education needed. Not enough supervision of a trainee who needs more instruction and support might negatively impact patient care and not give trainees the education they need.

Dr. Shen

Yet Jenny Y. Shen, MD, FHM, an academic hospitalist and an associate professor of medicine and clinical nursing at the University of Rochester Medical Center, noted that in some cases it can inhibit trainee growth if one doesn’t grant them enough autonomy and responsibility. Input from the senior resident can be insightful in gauging this, as can context from the previous hospitalist on the service.

Getting a sense of learners’ goals can be another helpful part of getting to know the team. Dr. Lane has all her trainees set a goal for the time they will be together on service using a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goals format. This helps guide trainee growth and can inform evaluation as well.

In general, being clear about setting expectations with trainees can help with both clinical efficiency and learner growth. Dr. Lane shares a list of expectations with her trainees at the beginning of service, tailored to individuals at different levels of training, and she also provides expectations they should have for her.

Preparation, organization, and prioritization

Part of setting clear expectations is being clear, thoughtful, and consistent about scheduling and the team plan, setting a consistent time for rounds and checking back in later in the day. This helps both the supervising hospitalist and the trainees be most efficient with their time, leaving more opportunities for student education and other tasks.

Dr. Sharpe

Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, SFHM, is a professor of clinical medicine and a clinician-educator in the division of hospital medicine at University of California San Francisco Health in San Francisco. He pointed out that when setting times to meet, it’s important to keep in mind relevant aspects of the schedule, such as when medical students will be unavailable due to afternoon conferences.

The schedule and timeline for rounds can vary somewhat based on institutional structures and personal preference. But for clinical and workflow efficiency, it’s important not to let them extend for too long, said Dr. Shen.

Pre-rounding by the hospitalist, when possible, can be an important part of making the most out of rounds, both clinically and for educational aspects. Dr. Smith always pre-rounds on his patients and starts his notes and task lists before meeting with his team, who have already done their own initial assessments. This helps streamline the later discussion with the team on patient plans.

“If you have all the information at hand that you need to be able to move through the aspects of clinical care, you create efficiency,” said Dr. Smith. “Then you can talk more about what’s actually going on with the patients, focus time on clinical reasoning, and make point-of-care teaching points.”

Dr. Lane also uses that pre-rounding time to pick out a few teaching topics that apply to the current patient load, pulling out teaching resources (e.g., recent guidelines) that might be applicable. “I don’t want to fall into the trap of trying to teach every single little thing,” she said. “I want to make sure that that burst of team rounding time is high-yield for our patients and learners. Sometimes other educational things can come later, like in the afternoon, when you have more time.”

Dr. Shen also noted that sometimes she must get clinically oriented with the patient before adding in the educational element. “If I’m really comfortable with the clinical scenario then I clear out my bandwidth to actually be assessing the interactions between the students and the residents.”

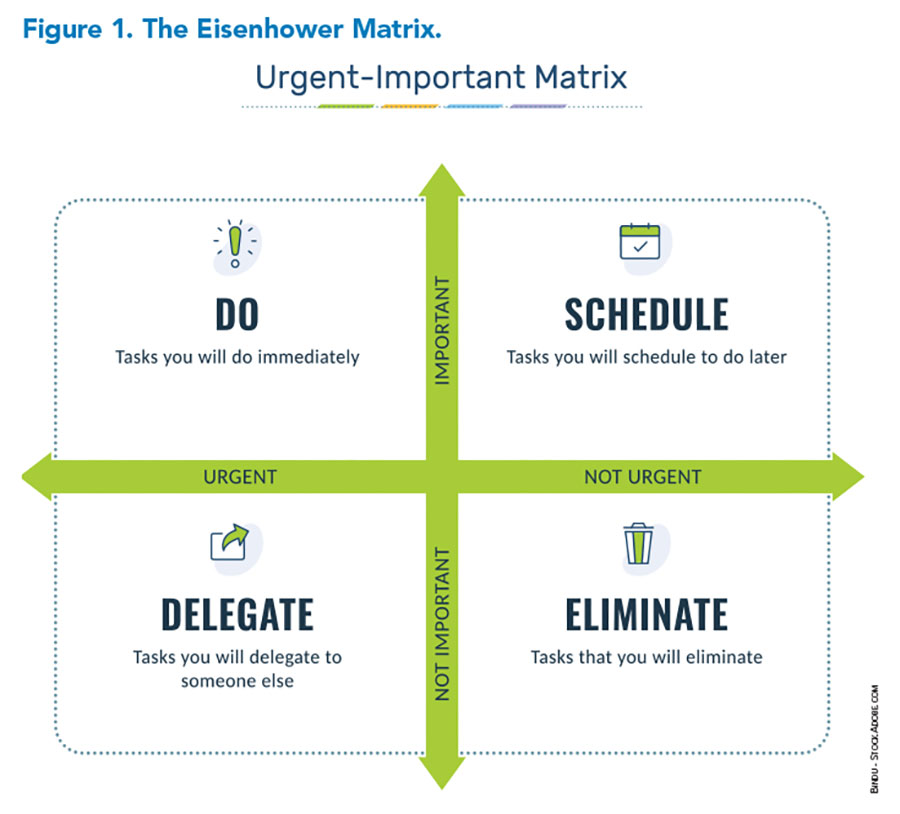

Another key aspect of prioritization is simply recognizing which elements are urgent and important and must be done immediately. Other tasks, like aspects of trainee education, might need to be scheduled, as they are important but not urgently needed at a specific moment. Tasks that are time-sensitive but not important might best be delegated, and those that are neither urgent nor important might best be deleted (see Figure 1).

Role-modeling and multitasking versus time blocking

A paradox of time management on the wards is that both multitasking and time-block compartmentalization can be essential for balancing clinical responsibilities, educational goals, and other tasks.

For example, Dr. Smith compartmentalizes certain necessary tasks that don’t directly pertain to clinical care that he might be able to take care of before or after rounds. “You can separate those tasks, so your overarching to-do list is not too long at the end of the day. This allows you to focus on the patient care that you’re providing and not be distracted by pending tasks outside of the clinical context.”

It may be helpful to block time in the afternoon for additional tasks like seeing additional patients not on the teaching team or performing tasks related to academic medicine, and knowing the schedule can help one find appropriate times for this. However, Dr. Sharpe noted that it’s important not to overbook this time, as it can decrease one’s availability to the team and impair educational opportunities.

Finding time for didactics in the afternoon can be beneficial, noted Dr. Sharpe, but it’s often best to keep this relatively short (probably no more than 15 to 20 minutes). However, such didactic sessions are not the only approach to education, as education can be built into each clinical encounter.

Dr. Shen shared, “I believe that, to balance the teaching and the clinical work, you have to combine them both.” As much as possible, she multitasks and interweaves the education aspect with patient care. Instead of quizzing or lecturing, she focuses on guiding trainees through practical applications of their medical knowledge, troubleshooting more challenging cases with them, and referring them to additional resources as needed.

Positive role modeling is also a critical part of education while on service. Sometimes, Dr. Lane purposefully takes over an element from her senior resident because she wants to demonstrate how she would do it for the benefit of the trainees.

“It’s really the best to role model what you are trying to teach,” said Dr. Smith. “But you must be particularly mindful of that because you can unintentionally role model bad behaviors as well. Approaching patients and learners similarly with an outward mindset can protect us as hospitalists from making that error.”

Balancing academic medicine responsibilities

More broadly, it’s incredibly challenging to balance the responsibilities of academic medicine with the clinical responsibilities of being a hospitalist. While on clinical service, hospitalists face long, intense clinical days.

“Yet you are also expected to be working on that abstract, going to meetings, teaching, and performing other tasks. So how do you balance that?” asked Dr. Sharpe. “It’s almost like two full-time jobs you’re supposed to be doing at the same time.”

For those who truly desire a successful career as an academic hospitalist, Dr. Sharpe noted that it’s important to anticipate the time that one will be on service and allocate time appropriately. It’s helpful to complete as many academic tasks as possible while off service. To be successful as an academic, it’s simply not possible to take as much time off between hospital service periods as one might as a community hospitalist.

Although this may vary based on institutional culture and personal preference, it may also be helpful to put an “out of office” message on one’s email while on service so that people know response times may be delayed. Dr. Sharpe added that it’s also important to know one’s personal rhythms and commitments and schedule around that, e.g., find an hour to answer emails in the early mornings or late evenings.

To help keep projects moving, sometimes it’s possible to sneak in a meeting with one’s collaborators while one is on service, Dr. Lane shared, although it’s important not to overbook. It’s key to prioritize one’s tasks in the limited time that is available and not get bogged down in less urgent tasks like answering the email at the top of one’s inbox. Even more broadly, it’s key to learn how to say no when needed and be intentional about the broader commitments one accepts.

Dr. Sharpe also urges self-forgiveness and sincere apologies if you miss a deadline or don’t get back to someone. The patients must come first and the trainees second, and so sometimes things are going to be missed.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Bloomington, Ind., and a freelance medical writer.

References

- Readlynn J, et al. Preparing future generations of hospitalist educators. J Hosp Med. 2023;18(10):875-876. doi: 10.1002/jhm.13188.

- Larsen T, et al. The role of the hospitalist in the clinical education of medical students. J Brown Hosp Med. 2023;2(4). doi:10.56305/001c.87819