It’s 8 a.m. and the hospital is starting the day in a tough position. There are 15 patients boarding in the emergency department (ED), two patients who can be downgraded from the intensive care unit, and another five admissions planned from the post-anesthesia care unit. Hospital leadership is requesting hospitalists prioritize early discharges to accommodate the bed needs of those waiting for admission. Determining how to tackle the day differently and with urgency can be challenging given the number of issues that may seem to be out of the hospitalist’s control.

ED crowding is an unfortunately common occurrence that has troubled hospitals across the nation for decades. Crowding is defined to occur “when the identified need for emergency services exceeds available resources for patient care in the ED, hospital or both.”1 ED, boarded, and admitted patients have been shown to have an increase in morbidity and mortality as a result of crowding and prolonged wait times.2 A recent study based in the U.K. stated “For every 82 admitted patients whose time to inpatient bed transfer is delayed beyond 6 to 8 hours from time of arrival at the ED, there is one extra death.”3 ED crowding is also correlated with “increased violence toward staff, high clinician and nursing staff turnover, decreased provider productivity, increased staff distraction resulting in human error, and consequent legal action.”4

Multiple causes lead to ED boarding. On a larger scale, there are healthcare system economic structures along with a lack of healthcare capacity in play.4 On a more focused scale, ED boarding is a result of issues with patient flow. This can be broken down into an input, throughput, and output framework. Increased input of patients is driven by an aging, more acute, patient population and by lack of access to outpatient services. Poor throughput can be attributed to a lack of care-delivery standardization, a mismatch of bed capacity and demand, delays in treatment, and staffing gaps. Decreased output can be attributed to competing clinical priorities, lack of post-acute care availability, and patient discharge delays due to clinical and nonclinical barriers. When organizations face throughput challenges, hospitalist teams are often called to improve output. This can be seen in several familiar initiatives such as early rounding and discharges prior to noon.

To create additional capacity with the finite number of inpatient beds available, we implemented an Expediting Team and a Departure Lounge. We hypothesized that if a dedicated team was tasked with addressing patient flow barriers while simultaneously operating a Departure Lounge for discharged patients, we would create additional hospital bed capacity. Clinical and nonclinical barriers to address included pending radiology testing, consultant input, physical therapy, medication or durable medical equipment delivery, delay in transportation home, or further discharge instructions.

Setting up an Expediting Team

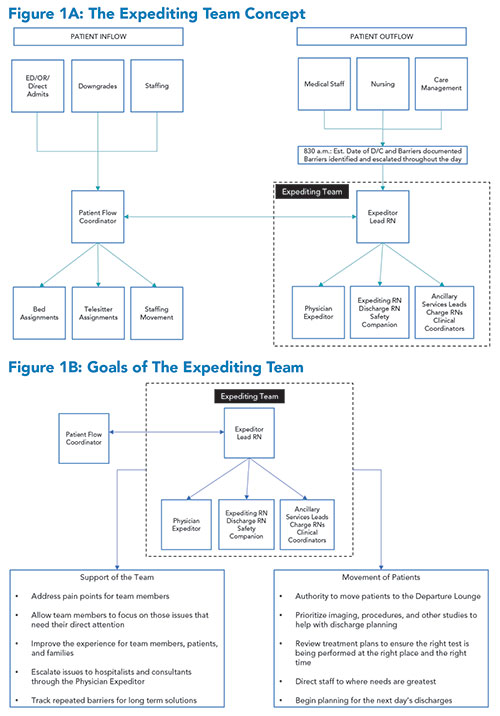

The Expediting Team consists of an expediting nurse, an expediting physician, a discharge nurse, and a nursing companion. This team focuses on collaborating with the frontline staff to identify any barriers to throughput and works to remove these obstacles with the expectation of achieving an earlier discharge time. (Figures 1A, 1B)

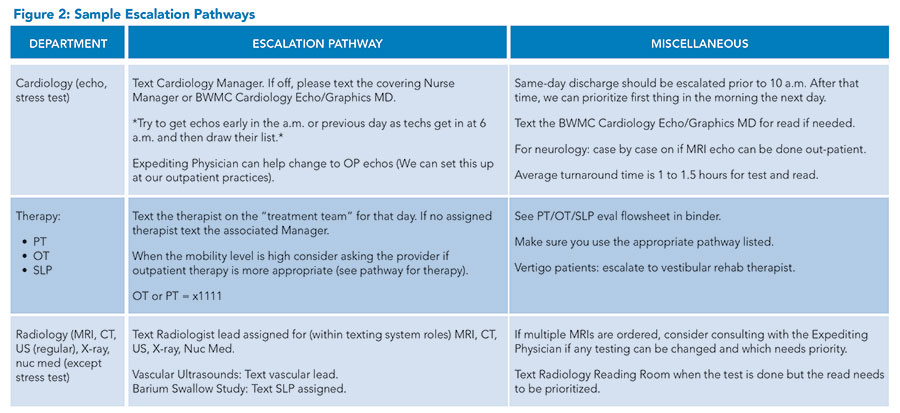

The Team starts the day obtaining and acting on information regarding the planned discharges for that day and the following day. The main driver for this is a daily 9:00 a.m. secure text message the expediting nurse sends to rounding hospitalists asking for all barriers to discharge. The expediting nurse then escalates the need to the correct department using newly created Escalation Pathways (Figure 2).

The Team starts the day obtaining and acting on information regarding the planned discharges for that day and the following day. The main driver for this is a daily 9:00 a.m. secure text message the expediting nurse sends to rounding hospitalists asking for all barriers to discharge. The expediting nurse then escalates the need to the correct department using newly created Escalation Pathways (Figure 2).

These pathways allow the ancillary departments to prioritize their work based on the greatest need. This collaboration also improves communication from the ancillary departments back to the expediting nurse. For example, if the radiology department is down several techs, the expediting nurse would then work with the expediting physician to determine which tests could be safely performed as an outpatient to avoid a bottleneck within the radiology department.

These pathways also grew to encompass the ability to direct staff to the greatest need. For example, home oxygen testing can be a barrier to discharge. Nursing primarily performs this test. However, when the inpatient unit capacity and acuity are high, the frontline nursing staff may be unable to complete this timely. The expediting nurse would then redirect respiratory therapists to perform home oxygen testing to avoid another delay.

The expediting physician plays an active role with access to all secure text messaging that occurs between the expediting nurse, medical staff, nursing, and others. Interventions by the expediting physician include:

- Identifying outpatient over inpatient testing opportunities

- Assisting in tertiary care center transfers

- Assisting in medical staff-related escalations (consults, testing results)

- Collaborating with the expediting nurse and patient flow coordinator to redirect medical staff based on the greatest need

- Identifying ED boarders that can be discharged

- Providing verbal handoff to the outpatient physician accepting the patient post-discharge

Setting up a Departure Lounge

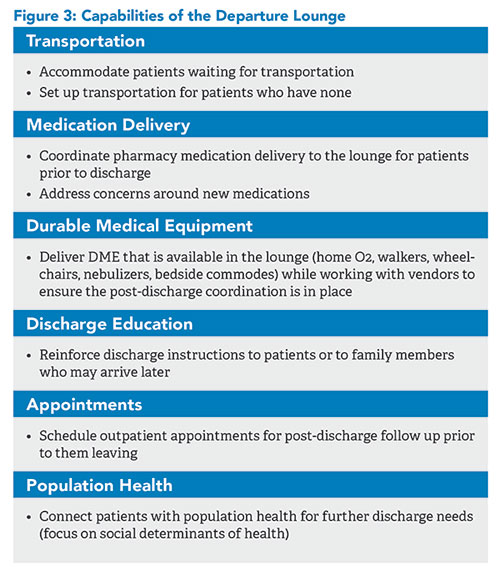

In addition to addressing barriers throughout the hospital, the expediting nurse, in partnership with a nursing companion, is responsible for oversight of the Departure Lounge. The Lounge is open from 8 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., Monday to Friday. Based on previous attempts to open a Departure Lounge, we learned the importance of location, amenities, patient selection, and staff buy-in. The location of the Lounge is just off the hospital’s main entrance to make it easily accessible for patients’ families. The Lounge has light refreshments, comfortable chairs, and entertainment such as TVs, iPads, and puzzles. It also has areas for privacy and spaces that can accommodate contact-isolation patients. The inclusion criteria were simple—patients need to be alert and oriented with the ability to ambulate with minimal assistance.

Drawing from our hospital’s previous attempts, the process of identifying patients was critical. Previously, frontline nursing and clinicians would be the primary drivers in identifying who was appropriate. In our current design, the expediting nurse identifies patients based on discharge orders visible in the electronic health record. They would then “pull” patients to the Lounge by reaching out to the primary nurse to discuss the patient’s care. This process, along with expanding the capabilities of the lounge (Figure 3) to include durable medical equipment delivery and medication delivery, has proven to be effective in increasing utilization.

While the primary focus of the Departure Lounge was to have a place for patients to wait safely post-discharge to free up inpatient capacity, it has since expanded. Now the Lounge has the capabilities to set up post-discharge care for high-need population patients and perform discharges.

While the primary focus of the Departure Lounge was to have a place for patients to wait safely post-discharge to free up inpatient capacity, it has since expanded. Now the Lounge has the capabilities to set up post-discharge care for high-need population patients and perform discharges.

For example, the hospitalist may identify a diabetic patient as high risk for readmissions and medication issues. This is then communicated to the Expediting Team who will bring the patient to the lounge. Medications will be delivered to the patient’s bedside and affordability concerns can be addressed at that time. Arrangements will be made so the patient can meet with the diabetic educator and a member of the outpatient team. They will then get a follow-up appointment scheduled by the Lounge staff. This touchpoint with the outpatient team while still in the hospital helps form a relationship to aid in the transition of care to a home setting. The hospital’s population health team can aid in any outstanding issues that may need to be further addressed at home such as meal plans or other social determinants of health.

Lastly, the Departure Lounge has recently expanded to include the ability to perform discharges in the Lounge itself. This has given us the ability to free up inpatient capacity earlier in the day and has improved patient engagement in the discharge process itself, including increased use of scheduling appointments.

Outcomes

Comparing our base metrics to those one year with the Expediting Team in place, there has been a:

- 41.7% improvement in discharges before noon (17% versus 12%)

- 38.9% improvement in discharges before 2 p.m. (39.6% versus 32.1%)

- 9.6% improvement in time from discharge order to discharge completion (2 hours 30 minutes versus 2 hours 46 minutes)

- 27-minute improvement in discharge time of day (2:49 p.m. versus 3:16 p.m.)

Expediting Team escalation results include:

- An average of 11 clinical escalations for barriers to discharge per day

- The top five categories are: rehabilitation services (physical or occupational therapy or speech-language pathology); cardiology testing (echocardiogram, stress test); home oxygen (testing and delivery); radiology testing and reads; consultant clearance

- More than 98% of these escalations were completed on the same day

The Departure Lounge has seen the following:

- Lounge currently serves 18.8 patients per day

- Patients spend on average 32 minutes in the lounge

- Has served 3,500 patients in the 15 months it has been open

- Total time spent in the Lounge is 1,918 hours or 80 patient days

- The growth of the Lounge has steadily increased month over month as demonstrated below

Bottom line

Implementing an Expediting Team and Departure Lounge to eliminate clinical and non-clinical barriers to discharge can lead to sustained improvements in earlier discharges, decreased lengths of stay, and smoother transitions in care, proving to be an effective strategy to improve patient throughput and improving accessible care in a safe environment for patients and staff.

Dr. Tella

Dr. Vibhakar

Ms. Kippeny

Ms.Stauder

Dr. Tella is a hospitalist/physician advisor at the University of Maryland at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Baltimore. Dr. Vibhakar is the senior vice president and associate chief clinical officer for the University of Maryland Medical System. Ms. Kippeny is the nurse manager of nursing support services and patient placement at the University of Maryland at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Baltimore. Ms. Stauder is a discharge expediting nurse in nursing support services at the University of Maryland at Baltimore Washington Medical Center in Baltimore.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. https://doi.org/10.17226/11621. Accessed December 1, 2024.

- Morley C, et al. Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0203316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203316.

- Jones S, et al. Association between delays to patient admission from the emergency department and all-cause 30-day mortality. Emerg Med J. 2022;39:168-73.

- Kelen GD, et al. Emergency department crowding: the canary in the health care system. NEJM Catalyst. 2021; 5(2).

- Kelen GD and Scheulen JJ. Commentary: emergency department crowding as an ethical issue. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:751-4.

- Forster AJ, et al. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:127-33.

- Laam LA, et al. Quantifying the impact of patient boarding on emergency department length of stay: all admitted patients are negatively affected by boarding. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(2):e12401. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12401.

Is the expediting team additional staff to the rounding/admitting team? More specifically, is the physician additional to the “base” physician staffing team? Do you run this team 7 days a week?

A bonus benefit is that clearing beds sooner can result in an increase in admissions and revenue.