Prescription drug costs in the U.S. are among the highest in the world, surpassing those in other high-income nations by more than two and a half times. In 2023, the U.S. healthcare system’s total drug expenditure soared to an unprecedented $722.5 billion, driven by increased spending per prescription, higher drug utilization, and the ongoing development of new medications.1 The financial strain from these rising costs is felt across all sectors of healthcare, including patients, payers, prescribers, and policymakers. A 2024 Kaiser Family Foundation national poll revealed that 55% of Americans are concerned about drug affordability, with 21% admitting they skipped filling a prescription due to cost, opting instead for over-the-counter alternatives.2

The root of the U.S.’s high prescription drug prices lies in its unique system, which allows pharmaceutical manufacturers to set their own prices for products. Unlike other advanced nations where national health insurance systems negotiate or cap drug prices based on their therapeutic value, the U.S. has historically lacked mechanisms for such price regulation. For instance, in England and Wales, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence uses a cost-utility threshold of £20,000 to £30,000 ($25,000 to $40,000) per quality-adjusted life year to determine whether a new drug should be covered under the National Health Service (NHS).3 Drug companies’ ability to maintain such high prices in the U.S. is due to two factors: protection from competition and negotiating power.

Among public payers, Medicare covers approximately 67 million adults, most aged 65 years and older, for outpatient (Part D) and inpatient (Part B) drug costs. Medicaid, the federal- and state-funded health insurance program for low-income individuals, covers prescription drug costs for another 72 million Americans.4 Other public payers include the Veterans Health Administration, the Department of Defense healthcare system, state prison systems, and the federal employee health benefits program. Prior to 2022, Medicare and Medicaid were prevented by federal law from leveraging their purchasing power to secure lower drug prices while still required to provide broad coverage for therapeutic medications.

The Inflation Reduction Act: a turning point

In August 2022, the Biden-Harris Administration introduced the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) as a landmark measure to curb drug costs and expand benefits for Medicare beneficiaries. A cornerstone of the IRA is the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, which for the first time in U.S. history empowers the federal government to negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs without generic or biosimilar competition.

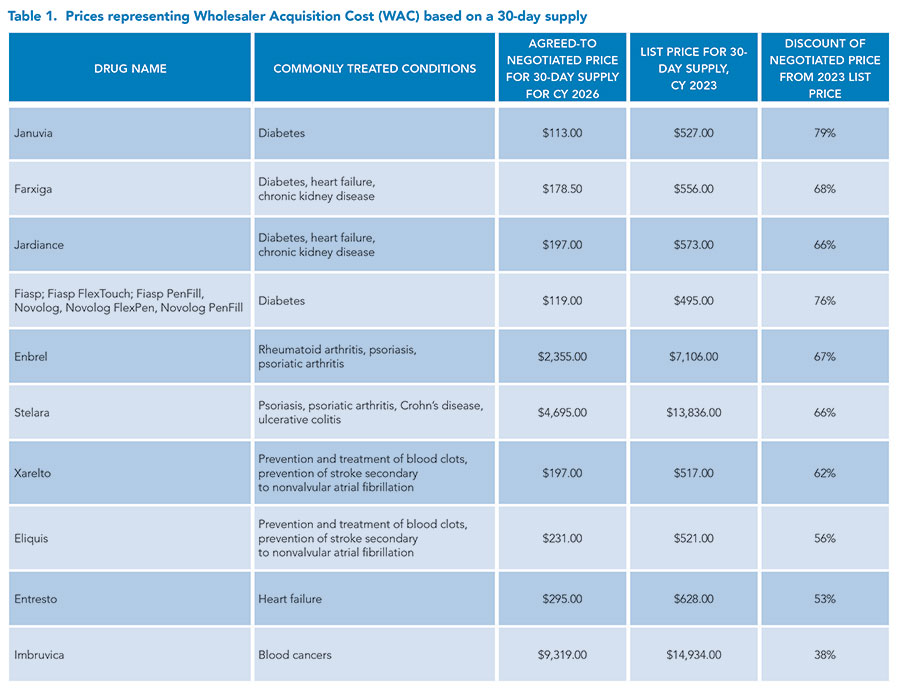

The IRA includes provisions projected to save Medicare beneficiaries approximately $1.5 billion annually in out-of-pocket expenses once fully implemented. The first round of negotiations in 2023 targeted 10 drugs that collectively accounted for 20% of Medicare Part D’s gross prescription drug costs and $3.9 billion in out-of-pocket expenses for beneficiaries.5 These medications, which treat conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, cancer, and autoimmune diseases, will have negotiated prices implemented by 2026.

The scope of negotiations will expand over time:

- 2026: 10 Part D drugs

- 2027: 15 Part D drugs

- 2028: 15 additional Part D and Part B drugs

- 2029 and beyond: 20 additional Part D and Part B drugs annually

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act’s prescription drug provisions include: establishing the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, requiring drug companies to provide Medicare with rebates if drug prices rise faster than inflation, capping yearly out-of-pocket spending for Medicare Part D enrollees to $2,000, limiting monthly insulin cost to $35 for Medicare Part D enrollees, limiting cost sharing for adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D, expanding low-income subsidy program under Medicare Part D to 150% of the federal poverty level, and getting rid of the “donut hole” coverage gap for patients starting this year.

These selections will focus on medications with the highest Medicare spending, ensuring that savings benefit the greatest number of beneficiaries. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the drug negotiation provisions will save Medicare $98.5 billion over 10 years (2022 to 2031).6 See Table 1.

Physicians’ view: ethical alignment with practical concerns

From the physician’s perspective, the IRA represents a significant step toward reducing healthcare inequities. By improving medication affordability, the IRA promotes better medication adherence, which is critical for managing chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension. Patients are more likely to fill and take prescribed medications when they are affordable, reducing the risk of complications and hospitalizations. We see patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who can ill afford their inhalers and have recurrent exacerbations due to the inability to get adequate inhalers to control their symptoms. Given the recent introduction of price caps, some companies have voluntarily introduced price caps for their inhalers before one is enforced on them.

- Multiple inhalers now are price-capped at $35:

- Atrovent HFA (ipratropium bromide HFA) inhalation aerosol

- Combivent Respimat (ipratropium bromide and albuterol) inhalation spray

- Spiriva HandiHaler (tiotropium bromide inhalation powder)

- Spiriva Respimat 1.25 mcg (tiotropium bromide) inhalation spray

- Spiriva Respimat 2.5 mcg (tiotropium bromide) inhalation spray

- Stiolto Respimat (tiotropium bromide and olodaterol) inhalation spray

- Striverdi Respimat (olodaterol) inhalation spray

- Airsupra (albuterol and budesonide)

- Bevespi Aerosphere (glycopyrrolate and formoterol fumarate) inhalation aerosol

- Breztri Aerosphere (budesonide, glycopyrrolate, and formoterol fumarate) inhalation aerosol

- Symbicort (budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate) inhalation aerosol

- Advair Diskus (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder)

- Advair HFA (fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation aerosol)

- Anoro Ellipta (umeclidinium and vilanterol inhalation powder)

- Arnuity Ellipta (fluticasone furoate inhalation powder)

- Breo Ellipta (fluticasone furoate and vilanterol inhalation powder)

- Incruse Ellipta (umeclidinium inhalation powder)

- Serevent Diskus (salmeterol xinafoate inhalation powder)

- Trelegy Ellipta (fluticasone furoate, umeclidinium, and vilanterol inhalation powder)

- Ventolin HFA (albuterol sulfate inhalation aerosol)

However, there could be some potential challenges consequently.

Impact on Innovation: Pharmaceutical companies argue that price controls could discourage investment in research and development, slowing the pipeline for new therapies. While the CBO estimates only a modest impact—13 fewer new drugs out of 1,300 over the next 30 years—we worry that any delay in innovation could affect their ability to offer cutting-edge treatments.

Administrative Burdens: Price negotiations may lead to stricter insurance formularies and increased requirements for prior authorizations. We already face substantial administrative workloads, and additional hurdles could detract from patient care.

Despite these concerns, most physicians support the IRA’s goal of making life-saving medications accessible to all patients, particularly those in vulnerable populations. Lowering drug costs aligns with the broader ethical mission of healthcare to reduce disparities and improve outcomes for underserved communities.

Pharmacists’ role: advocates for affordability and access

Pharmacists, who often serve as the first point of contact for patients navigating prescription costs, are also optimistic about the IRA’s potential benefits.

From a pharmacist’s perspective, the IRA will offer millions of Americans essential cost savings by lessening out-of-pocket spending for prescription medications, as we commonly encounter patients who express concern for medication affordability in addition to other life necessities. This leads to reduced medication compliance. For example, a newly diagnosed heart failure patient with reduced ejection fraction would be expected to start at least four to five medications, some of which are brand-name only. Assuming the patient is not in a coverage cap, their monthly heart failure medication copays alone will be over $100. If this copay is unfeasible, the care team will be faced with a challenging decision and likely need to defer starting guideline-recommended therapies, ultimately impacting the patient’s overall mortality risk. Therefore, the implementation of the $2,000 out-of-pocket yearly prescription-drug cap, monthly insulin price caps, eliminating the coverage gap, and the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program provisions will help relieve financial burdens and improve medication access and health outcomes across the country.

Drug shortages are a common occurrence in the healthcare system and impact clinical decision making daily. Another provision that has a beneficial impact on patients is the implementation of the Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program designed to offset the rise in drug prices secondary to ongoing drug shortages. This program will require pharmaceutical companies to pay Medicare rebates if Medicare Part B or Part D prescription drugs or biosimilar prices increase faster than the rate of inflation.

Yet, some concerns remain.

Supply Chain Challenges: Price negotiations could lead pharmaceutical companies to prioritize the production of more profitable drugs, potentially causing shortages of less lucrative but equally critical medications.

Greater price transparency under the IRA can help pharmacists provide more accurate guidance to patients, reducing confusion and fostering trust.

The road ahead

The IRA’s provisions for drug price negotiations have the potential to save billions for both patients and the healthcare system. However, the future of these reforms is uncertain, particularly in the context of shifting political landscapes. The Act, passed through budget reconciliation, could be repealed or revised under a new administration.

For hospitalists, the IRA presents an opportunity to advocate for patients’ financial well-being while addressing systemic barriers to medication access. As the number of negotiated drugs expands, hospitalists will need to stay informed about formulary changes and collaborate with pharmacists to ensure seamless transitions for their patients.

While challenges remain, the IRA represents a critical step toward a more equitable healthcare system—one where life-saving medications are within reach for all who need them.

Dr. Mehta

Dr. Parton

Dr. Mehta is an academic hospitalist, medical director, and vice-chair of inpatient clinical affairs at the University of Cincinnati, and an assistant professor of medicine and core faculty in the internal medicine residency program at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, both in Cincinnati, Ohio. Dr. Parton is an internal medicine clinical pharmacy specialist at the University of Cincinnati and an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Pharmacy, both in Cincinnati, Ohio.

References

- Tichy EM, et al. National trends in prescription drug expenditures and projections for 2024. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2024;81(14):583-98. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxae105.

- Sparks G, et al. Public opinion on prescription drugs and their prices. KFF website. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/public-opinion-on-prescription-drugs-and-their-prices/. Published October 4, 2024. Accessed December 31, 2024.

- Kesselheim AS, et al. the high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.11237

- September 2024 Medicaid & CHIP enrollment data highlights. Medicaid website. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html. Updated December 27, 2024. Accessed December 31, 2024.

- Medicare drug price negotiation program: negotiated prices for initial price applicability year 2025. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/fact-sheet-negotiated-prices-initial-price-applicability-year-2026.pdf. Published August 2024. Accessed December 31, 2024.

- Congressional Budget Office cost estimate. CBO website. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-09/PL117-169_9-7-22.pdf. Published September 7, 2022. Accessed December 31, 2024.