Substance use disorders in physicians

The title of this article, a quote by F. Scott Fitzgerald, illustrates the experience of alcohol use disorder. Although physicians are comfortable recognizing and treating substance use disorders (SUDs) in patients, we rarely discuss how to recognize SUDs in ourselves and our peers. This article will provide a compassionate approach to identifying SUDs in ourselves and our peers, discuss the stigma and other barriers to treatment for SUDs, and describe what practical help can look like.

Stats and diagnosis

Before starting medical school, future physicians have statistically significantly lower rates of depression and burnout and score higher on quality-of-life surveys compared to their college graduate peers.1 During medical school and residency, this trend dramatically changes. Medical students and residents are more likely to be burned out and exhibit signs of depression compared to their age-matched college graduate peers. After completing training, physicians continue to have increased rates of burnout.2 Like the general population, as many as 50% of physicians with SUDs have comorbid psychiatric disorders.3 Previous cross-sectional surveys and review articles suggest that substances are often used by physicians for performance enhancement or as a treatment for pain, anxiety, or depression.4 When identifying a SUD in ourselves or a physician peer, we recommend framing the diagnosis through this empathetic lens of how our mental health can be impacted by external stressors, rather than one of blame and personal choice.

Before starting medical school, future physicians have statistically significantly lower rates of depression and burnout and score higher on quality-of-life surveys compared to their college graduate peers.1 During medical school and residency, this trend dramatically changes. Medical students and residents are more likely to be burned out and exhibit signs of depression compared to their age-matched college graduate peers. After completing training, physicians continue to have increased rates of burnout.2 Like the general population, as many as 50% of physicians with SUDs have comorbid psychiatric disorders.3 Previous cross-sectional surveys and review articles suggest that substances are often used by physicians for performance enhancement or as a treatment for pain, anxiety, or depression.4 When identifying a SUD in ourselves or a physician peer, we recommend framing the diagnosis through this empathetic lens of how our mental health can be impacted by external stressors, rather than one of blame and personal choice.

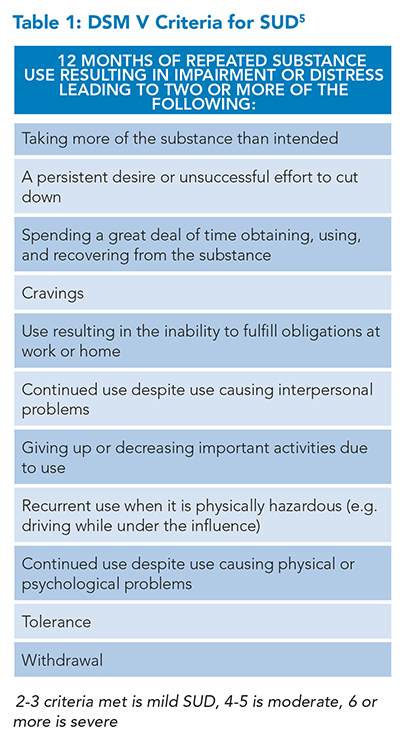

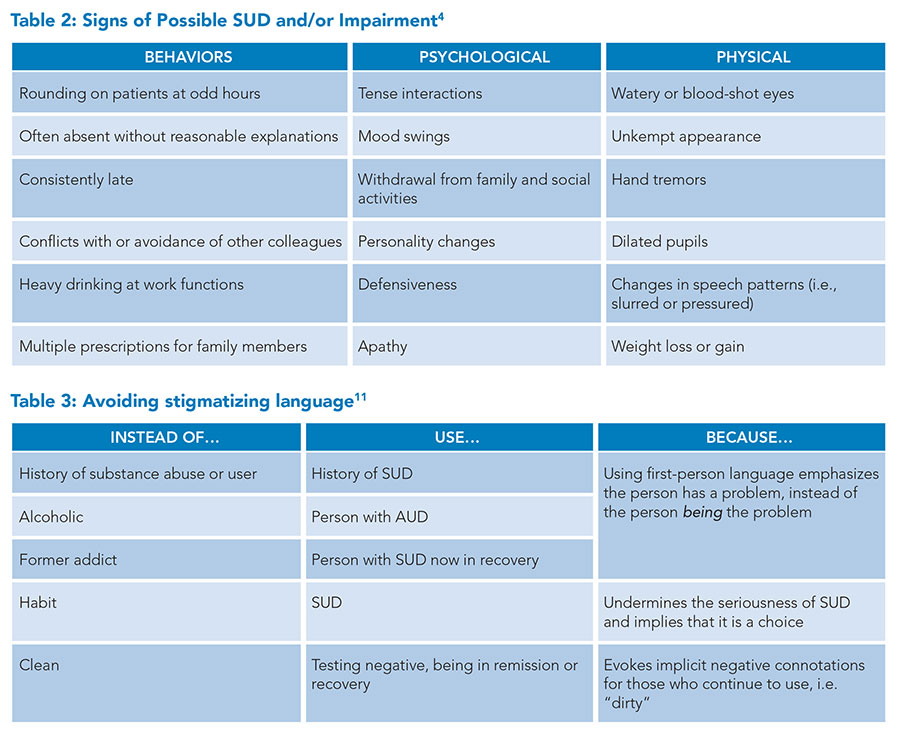

Diagnosis of a SUD, whether that be alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates, or others, can be made through the DSM V criteria for SUD, as illustrated in Table 1.5 Although it’s challenging to determine the exact prevalence of SUDs in physicians, studies suggest it ranges between 10 and 20%, similar to that of the general population.6-8 Despite historical prejudice against physicians with SUDs, physicians with SUDs are not necessarily impaired physicians. An impaired physician, as defined by the American Medical Association, is a physician who is unable to deliver medical care to patients safely and with reasonable skill. Instead, like any physician with a psychological or medical disorder, physicians with SUDs are considered to have a potentially impairing condition.8 Detecting signs of SUD and impairment in other physicians can be challenging. Table 2 includes common signs and symptoms.

Barriers to treatment

There are many barriers to treatment for physicians with SUDs, including stigma, denial, and fear of losing one’s reputation, income, and license to practice medicine. The routine frustrations many physicians face in the management of SUD further add a unique, work-related source of both external and internal stigmatization. Emergency department (ED) physicians are one of the specialties that often manage acute presentations of patients with SUD. A 2018 study in the Journal of Addiction Medicine showed that since patients with SUDs typically have needs that far exceed what an ED can provide, it isn’t surprising that only 8% of ED physicians said working with patients with SUDs who are in pain is “satisfying.” More than half of the ED physicians in the same survey indicated irritation and preference to avoid working with these patients, and a further 72% reported these patients were particularly difficult to work with.9 How this frustration may, along with the myriad other work-related stressors faced by this specialty, result in an increased avoidance and denial of one’s own SUD is not difficult to imagine.

There are many barriers to treatment for physicians with SUDs, including stigma, denial, and fear of losing one’s reputation, income, and license to practice medicine. The routine frustrations many physicians face in the management of SUD further add a unique, work-related source of both external and internal stigmatization. Emergency department (ED) physicians are one of the specialties that often manage acute presentations of patients with SUD. A 2018 study in the Journal of Addiction Medicine showed that since patients with SUDs typically have needs that far exceed what an ED can provide, it isn’t surprising that only 8% of ED physicians said working with patients with SUDs who are in pain is “satisfying.” More than half of the ED physicians in the same survey indicated irritation and preference to avoid working with these patients, and a further 72% reported these patients were particularly difficult to work with.9 How this frustration may, along with the myriad other work-related stressors faced by this specialty, result in an increased avoidance and denial of one’s own SUD is not difficult to imagine.

This stigma is thought to be part of the reason why only 10% of patients with SUDs seek treatment.10 There is evidence that stigma is reduced when we avoid using terms like “substance abuser” and instead use “person with SUD.” Physicians who avoid stigmatizing language are less likely to see patients as personally culpable for their pattern of use and instead more appropriately view the pattern of use as a dysregulated reward pathway in the brain. This leads us to see SUDs as a disease requiring medical treatment instead of a moral failing requiring punishment.10,11 To foster more compassionate and effective discussions about SUDs among ourselves and our physician peers, it’s essential to employ neutral language, as outlined in Table 3.

Despite physicians often having more insight into the diagnosis and treatment of SUDs compared to the general population, denial can often hinder treatment. Physicians are taught in training to be self-sufficient, and tireless, and to put patient care and their professional obligations before their own needs. One study of pediatric attending physicians and advanced practice clinicians showed that 83% of participants reported working while significantly ill in the last year, despite 95% of participants knowing that working while sick would put their patients at risk.12 These healthcare professionals reported that they continued to work because they did not want to let their colleagues or patients down. Denial of one’s own illness allows physicians to continue to work while knowing they shouldn’t work while sick. Similarly, it’s thought that denial of one’s own SUD, due to years of putting our patients’ and colleagues’ needs before our own, leads to delay in diagnosis or treatment.3,8

Many review articles also describe a “conspiracy of silence” among physician peers. Physicians often explain away their peers’ behavior or doubt their own observations due to concerns that they are overreacting. Furthermore, physicians also worry about damaging their colleagues’ careers or their hospital’s reputation by acknowledging the reality of an impaired physician. Despite clear guidelines from the American Medical Association mandating the reporting of impaired colleagues, some physicians still feel that it is the personal responsibility of the affected physician. Review articles suggest that physicians’ personal lives are often first affected by SUDs as they are highly motivated to continue to fulfill their professional obligations.3,4 However, family members of physicians may choose silence due to the loss of income that might occur if a SUD is diagnosed.3 This can lead to a more widespread culture of denial both in the workplace and at home. Unfortunately, this short-term goal of saving face can lead to more substantial harm as delays to treatment for SUD can lead to worse outcomes.10

Physicians with SUDs often have concerns about the implications for their careers. As stated above, a physician with a SUD or any mental health diagnosis has historically been conflated with an impaired physician. One study showed that of the 5,000 actions that were taken against physician licenses between 2004 and 2020, more than 75% were due to impairment related to SUD.13 This may lead to the belief that SUD is a career-ending diagnosis. However, physicians should instead be encouraged to seek timely help to continue practicing. In 2018, a report from the Federation of State Medical Boards recommended that state medical boards reconsider any probing questions about mental health or SUDs on license applications and renewals, as these questions were more likely to discourage physicians from seeking treatment than improve patient safety.14 Despite this, these questions are still asked on yearly license renewals in many states.

Getting help

Once we have identified an SUD in ourselves or another physician, the next step is to seek assistance through an employee assistance program, counseling, medical care, and support groups. Caduceus groups are peer support groups that consist entirely of medical professionals and use a 12-step approach to encourage recovery from SUDs. These groups are often helpful because healthcare professionals can share their experiences with others. The state medical society and the associated physician health program (PHP) can be good resources when you or a colleague are struggling with an SUD. These entities are usually separate from the state medical board which is responsible for licensure.4 If you or your colleague is unable to competently perform as a physician, the next step is to notify a supervisor to arrange for time off of work so a structured recovery plan can begin. Structured plans, called contingency contracts, can be provided by the state PHPs. These plans often involve a contract by which impaired physicians must participate in certain activities and document recovery from SUD to continue or return to practice, typically for five years.

If the physician does not comply with the contract, a common consequence is notification of the situation to the state medical board. Although there are valid criticisms of PHPs, studies show that physicians who participate in these programs have a much higher success rate (70%) than the general population does with usual treatment for SUDs.6,15 Despite the possibility of loss of licensure, the 2001 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations standards state: “The purpose of the process [of identifying and treating impaired physicians] is assistance and rehabilitation rather than discipline, to aid a physician in retaining optimal professional functioning, consistent with protection of patients.” It is in the best interests of physicians, patients, the government, and healthcare organizations for physicians with SUDs to recover and continue to practice.

Physicians with SUDs have made important contributions to healthcare. In Dr. William Osler’s article “The Inner History of the Johns Hopkins Hospital,” published in 1969, he describes the SUD of his friend William Halstead, the father of modern surgery. Dr. Osler states that Dr. Halstead’s “proneness to seclusion, the slight peculiarities amounting to eccentricities…were the only outward traces of the daily battle through which this brave fellow lived for years.”4

Like Dr. Osler, we need to approach SUD in ourselves and our fellow physicians with compassion. We should avoid dichotomizing physicians into either completely self-sufficient and infallible or weak and incompetent. We encourage you to avoid stigmatizing language, acknowledge that physicians like all humans are susceptible to disease, and break the conspiracy of silence to encourage timely diagnosis and treatment of physicians with SUDs.

Dr. Faulk

Dr. Patel

Dr. Chang

Dr. Dao

Dr. Wenzinger

Dr. Faulk is an assistant professor of medicine, director of resident well-being for the internal medicine residency program, and co-director of the internal medicine-advanced clinical rotation for the medical students at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Patel is an instructor in medicine in the division of hospital medicine, and co-director of resident education on hospital rotations at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Chang is an associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, the interprofessional education MD thread director, and co-director of the inpatient clinical immersion at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Dao is an assistant professor of medicine, a hospitalist, an associate program director for the internal medicine residency program, and director of OUTmed (an LGBTQIA+ group dedicated to advancing inclusion and education in the school of medicine), at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in St. Louis. Dr. Dao also serves on SHM’s DEI Committee. Dr. Wenzinger is an assistant professor of psychiatry in the division of child and adolescent psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine in St. Louis. He is also the medical director for inpatient child and adolescent psychiatry at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and a clinical leader in the CARE clinic, which provides SUD for women postpartum.

References

- Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520-1525.

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451.

- Vayr F, Herin F, et al. Barriers to seeking help for physicians with substance use disorder: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;199:116-121.

- Baldisseri MR. Impaired healthcare professional. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2 Suppl):S106-S116.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington D.C.: 2013.

- Rose JS, Campbell M, et al. Prognosis for emergency physician with substance abuse recovery: 5-year outcome study. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(1):20-25.

- Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30-38.

- Merlo LJ, Teitelbaum SA. Substance use disorders in physicians: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, identification, and engagement. In: Stein MB, ed. UpToDate website. Published 2022. Accessed September 4, 2024.

- Mendiola CK, Galleto G, et al. An exploration of emergency physicians’ attitudes toward patients with substance use disorder. J Addict Med. 2018;12(2):132-135.

- Kelly JF, Westerhoff CM. Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21(3):202-207.

- NIDAMED. Words matter: terms to use and avoid when talking about addiction. National Institutes of Health website. https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/nidamed_words_matter_terms.pdf. Published June 21, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2024.

- Szymczak JE, Smathers S, et al. reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick: a mixed-methods analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):815-821.

- Rotenstein LS, Dadlani A, et al. Patterns in Actions Against Physician Licenses Related to Substance Use and Psychological or Physical Impairment in the US From 2004 to 2020. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(6):e221163.

- Hengerer, AS et al. “Report and recommendation of the workgroup on physician wellness and burnout: adopted as policy by the Federation of State Medical Boards.” Federation of State Medical Boards website. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and-burnout.pdf. Published April 2018. Accessed September 4, 2024.

- Goldenberg M, Miotto K, et al. Outcomes of physicians with substance use disorders in state physician health programs: a narrative review. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2020;52(3):195-202.