An 8-year-old girl presents with five days of worsening cough. She has a temperature of 38.6 °C, a respiratory rate of 38, a blood pressure of 85/45, and a heart rate of 120. Pulse oximetry reveals an oxygen saturation of 85% in room air which improves to 95% after initiation of supplemental oxygen of 1L/min via nasal cannula. She is alert, interactive, and well-perfused. She is tachypneic and has right-sided crackles on lung auscultation. Her white blood cell count is 16,000/μL. Chest X-ray demonstrates a right-sided infiltrate, with a small effusion that blunts the costophrenic angle. A 20 ml/kg fluid bolus is given, and IV ampicillin is started. Antipyretics are given and the patient is admitted with concern for sepsis due to community-acquired pneumonia. One hour later, the patient’s temperature has normalized, and her heart rate has improved to 90. Her respiratory rate remains elevated at 36. She remains on supplemental oxygen.

Does this child have sepsis?

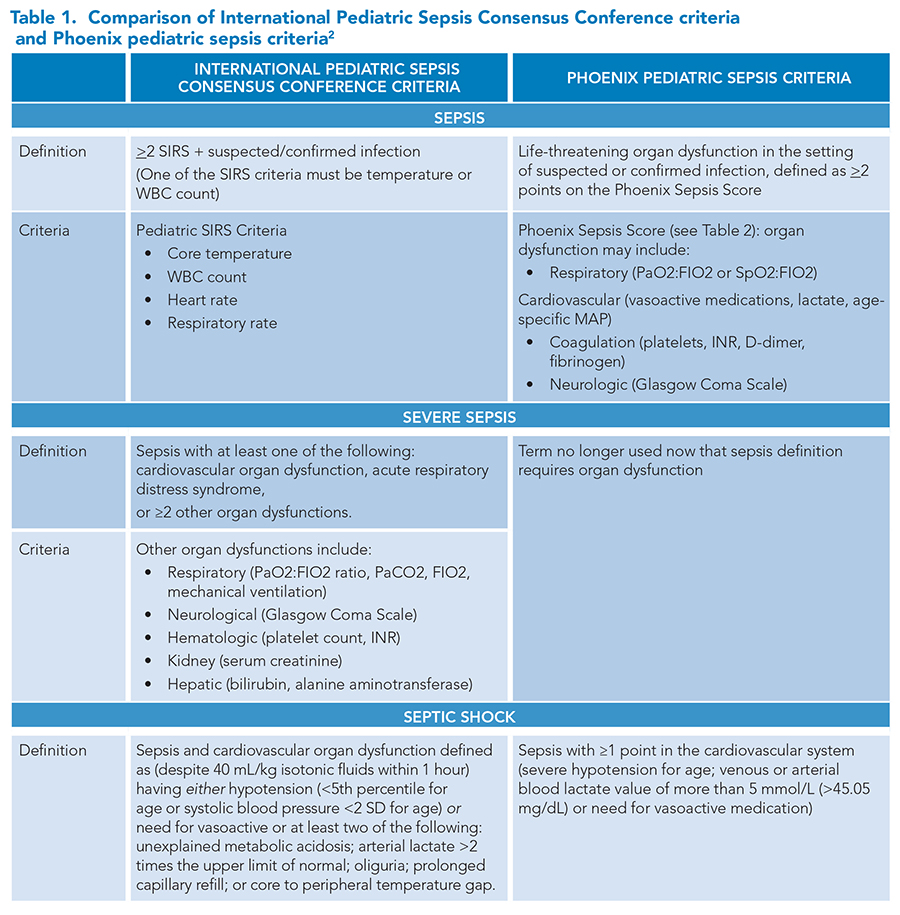

The definition of sepsis in adult and pediatric populations has changed in recent years. Prior to January 2024, the most recent pediatric-specific criteria for the diagnosis of sepsis were published in 2005 by the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference, defining sepsis as suspected or confirmed infection in the presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The group also developed definitions for severe sepsis and septic shock (Table 1).

The child in this case meets SIRS criteria for sepsis with fever, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and tachypnea for age. The SIRS-based definition of sepsis can detect children with mild illness severity, which can give clinicians advance warning but does not reliably identify children who are at risk of poor outcomes. The presence of a fever can elevate heart rate and respiratory rate—meaning that many febrile children with viral infections may meet SIRS criteria, but may not truly be at risk of adverse outcomes associated with sepsis. The child in this case had significant improvement in heart rate after fluid resuscitation and antipyretics.

The child in this case meets SIRS criteria for sepsis with fever, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and tachypnea for age. The SIRS-based definition of sepsis can detect children with mild illness severity, which can give clinicians advance warning but does not reliably identify children who are at risk of poor outcomes. The presence of a fever can elevate heart rate and respiratory rate—meaning that many febrile children with viral infections may meet SIRS criteria, but may not truly be at risk of adverse outcomes associated with sepsis. The child in this case had significant improvement in heart rate after fluid resuscitation and antipyretics.

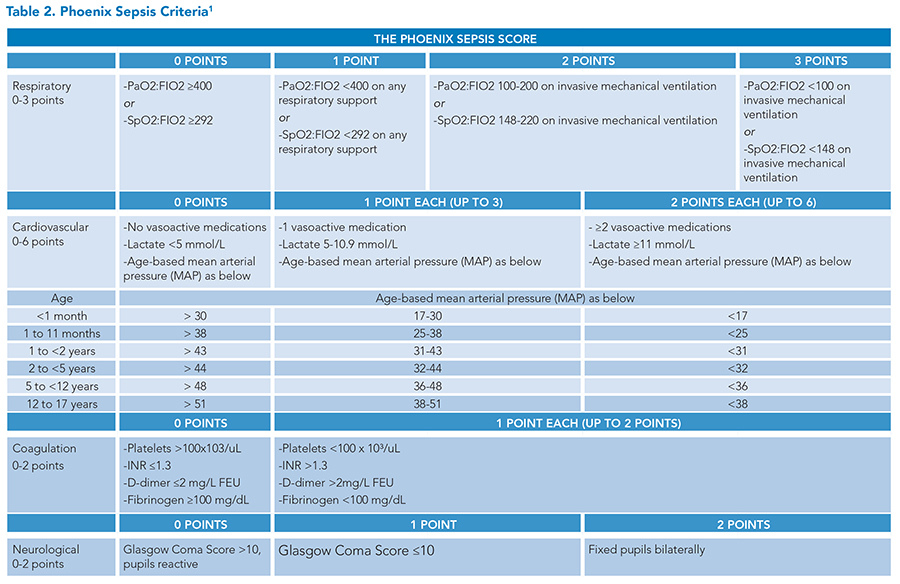

In January 2024, the Phoenix Sepsis Criteria were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, providing a new framework for the identification of sepsis and septic shock in children.1 The new criteria were developed through a multi-step process by a task force convened by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. First, the task force conducted an international study to determine how clinicians in a variety of pediatric fields diagnose and define sepsis. The task force determined a preference among pediatric providers that the term “sepsis” be limited to children with infection-associated organ dysfunction, rather than capturing all children who meet criteria for infection-associated SIRS. Following the international survey, the task force performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine factors that lead to adverse outcomes in children with infection. Then, via a cohort study and modified Delphi process, the task force developed organ-based criteria to identify pediatric sepsis. The task force found that a four-system model showed similar predictive value to an eight-system model. The Phoenix Sepsis Score was derived from the four-system model.

Phoenix Sepsis Score

The Phoenix sepsis criteria define sepsis as “potentially life-threatening dysfunction of the respiratory, cardiovascular, coagulation, and/or neurological systems.” The Phoenix Sepsis Score identifies children with suspected infection who have sepsis and septic shock (Table 2).

Sepsis = suspected infection and a Phoenix Sepsis Score of >2 points

Septic shock = sepsis and >1 cardiovascular point(s)

The Phoenix Sepsis Criteria apply to children under 18 years of age but do not apply to newborns during birth hospitalization or infants whose post-conceptual age is under 37 weeks.

Compared to the SIRS framework, the Phoenix Sepsis Criteria more reliably identify children with the highest risk of mortality. The Society of Critical Care Medicine task force found that:

- Children meeting Phoenix Criteria for sepsis had eight times the risk of in-hospital mortality compared to all children with infection.1,2

- Children meeting the criteria for severe sepsis had an in-hospital mortality rate of over 10% in high-resource settings and 33% in lower-resource settings. This corresponded to a 50% higher risk of mortality in children with severe sepsis than children with sepsis in higher-resource settings and a 20% higher risk in lower-resource settings.1

- Children with sepsis who score points on the Phoenix Sepsis Score for organ dysfunction limited to the primary organ (for example, a child with pneumonia scoring points for respiratory dysfunction) have a lower mortality rate than children with sepsis and remote organ dysfunction.

Back to the case

The next morning, a sepsis alert triggers for the patient. On your assessment, her respiratory rate is now 48, she is on 5 L/min of supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula, and she appears more tired and is notably less alert than the day before. Her capillary refill is very brisk. Her blood pressure is 72/40 (MAP of 51), her heart rate is 140, and her oxygen saturation is 93%. Repeat chest X-ray shows a worsening effusion, now taking up nearly half of the right hemithorax. You administer a 20 mL/kg normal saline bolus. You broaden her antibiotics to ceftriaxone and vancomycin. Chest ultrasound confirms a moderate-sized simple right-sided effusion. Labs now show a white blood cell count of 21,000/μL, a lactate of 2.1 mmol/L, and normal coagulation studies. A blood culture is obtained. You consult interventional radiology who places a chest tube, draining 300 mL of exudative fluid. With source control, she continues to improve. The chest tube is removed several days later, and she is transitioned to oral antibiotics in anticipation of discharge home.

While the Phoenix Sepsis Criteria predicts in-hospital mortality more reliably than prior sepsis criteria, including SIRS, fewer patients meet the criteria for sepsis and septic shock in the new Phoenix framework. This could lead to decreased early recognition of sepsis, especially outside of the ICU setting.

In this case, the child’s condition warrants urgent intervention, but she does not meet the criteria for sepsis in the Phoenix framework. This patient gets one point for having a SpO2:FIO2 ratio less than 292 but greater than 220, although calculating this statistic bedside for a patient on supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula comes with challenges. Since her MAP is greater than 48, her coagulation studies are normal, and her Glasgow coma scale is greater than 10, she gets no other points. With a total score of 1, she would not be classified as having sepsis on the Phoenix scale. However, most clinicians would evaluate and treat for sepsis as described in the case. Given this clinical picture, it would be inadvisable to wait to treat for sepsis until the patient had further deteriorated to meet the Phoenix criteria.

Key Takeaways

Recognizing and treating sepsis saves lives. Diagnostic criteria for sepsis have been refined over the years as more data is available at our fingertips, and there are advantages and disadvantages to each iteration. The newly defined Phoenix Pediatric Sepsis Criteria will be one valuable tool to identify the subset of children with the highest risk of mortality. The Phoenix criteria may be useful both clinically and for research. With the new criteria, the term “severe sepsis” is no longer used since by definition sepsis is severe and life-threatening. It is important to consider that prior SIRS-based criteria will still play a vital role in screening or recognizing patients with early signs of serious infection with impending end-organ dysfunction who require timely treatment, as relying on a higher threshold with Phoenix criteria may result in delays in identifying or treating patients. It is also worth noting that clinical documentation, billing, and coding changes are likely to lag, and utilizing SIRS with or without acute organ dysfunction to define sepsis and severe sepsis remains important for capturing illness severity and reimbursement.

Both SIRS-based and Phoenix criteria provide useful frameworks for thinking about whether a patient has sepsis. It is important to remember that the primary outcome for the development of the Phoenix model was mortality—an outcome we hope to never encounter on the general pediatric floors. We now find ourselves in a bit of a Goldilocks scenario—the SIRS criteria are too hot, and the Phoenix criteria are too cold (at least outside the ICU setting). In our opinion, the SIRS criteria remain a useful framework for screening and early warning, particularly given the critical importance of rapid intervention and treatment. Regardless of the criteria used, the clinical phenomenon of sepsis, and shock more generally, highlights the fact that computer algorithms do not replace the clinician at the bedside. Clinical judgment and careful, repeated assessment remain a mainstay of safe, effective, and compassionate care of the acutely ill child.

Dr. Hadley

Dr. Kort

Dr. Wimberly

Dr. Hadley is an assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital of Corewell Health, both in Grand Rapids, Mich. Dr. Kort is a pediatric hospitalist at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital of Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Mich. Dr. Wimberly is a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Ky.

References

- Schlapbach LJ, Watson RS, et al. International consensus criteria for pediatric sepsis and septic shock. JAMA. 2024;331(8):665-74.

- Carlton EF, Perry-Eaddy MA, et al. Context and implications of the new pediatric sepsis criteria. JAMA. 2024;331(8):646-9.

It would have helped clinicians greatly if the Phoenix score was compared with the SOFA score in effectiveness. How does the Phoenix score differ from the SOFA score?