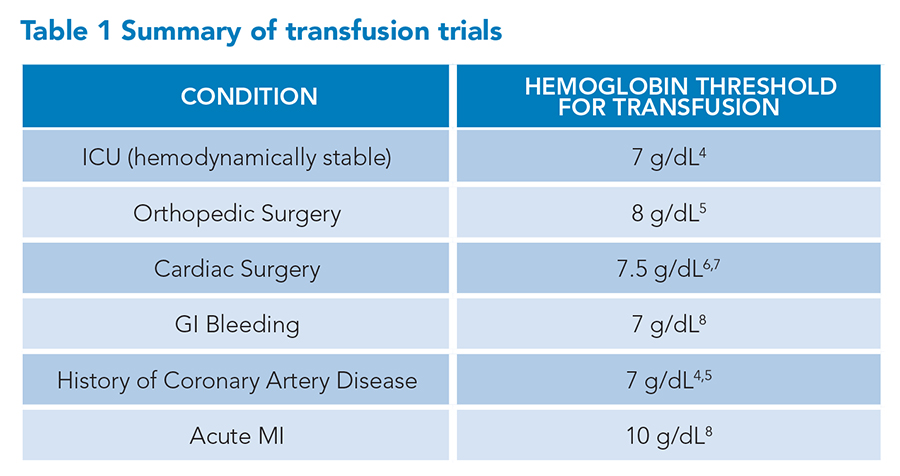

Over the past decade, there has been widespread adoption of restrictive red blood cell (RBC) transfusion guidelines.1,2 As a result, RBC transfusions have significantly decreased per hospitalization.3 In Table 1, we summarize the RBC transfusion thresholds supported by current clinical evidence and the most recent Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (AABB) guidelines, published in 2023. However, there are important nuances to the evidence supporting these guidelines, especially as it relates to RBC transfusions in the setting of acute myocardial infarction.

Due to these nuances, adherence to guidelines should not replace our clinical judgment. Take the following case: A 72-year-old with hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presents with an acute on chronic diabetic foot ulcer that began draining three days ago, requiring initiation of antibiotics. On day one of admission, hemoglobin is found to be 7.2 g/dL which is near the patient’s baseline. A workup reveals this is likely anemia of chronic disease. On day two of admission, morning labs reveal a hemoglobin of 6.8 g/dL, and the overnight team transfuses one unit of packed red blood cells, resulting in a repeat hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dL.

Due to these nuances, adherence to guidelines should not replace our clinical judgment. Take the following case: A 72-year-old with hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presents with an acute on chronic diabetic foot ulcer that began draining three days ago, requiring initiation of antibiotics. On day one of admission, hemoglobin is found to be 7.2 g/dL which is near the patient’s baseline. A workup reveals this is likely anemia of chronic disease. On day two of admission, morning labs reveal a hemoglobin of 6.8 g/dL, and the overnight team transfuses one unit of packed red blood cells, resulting in a repeat hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dL.

At first glance, this is a routine transfusion that follows guidelines, but we must answer the following clinical question: Did this RBC transfusion benefit the patient? We would argue that it did not.

In examining the RBC transfusion trials summarized in Table 1, it is important not to equate non-inferiority with benefit. The Table 1 RBC transfusion trials all showed a significant decrease in total RBC transfusions. All but one showed non-inferiority in clinical outcomes between a restrictive transfusion strategy (transfusing only for hemoglobin <7 to 8 g/dL) versus a liberal transfusion strategy (transfusing for hemoglobin <10 g/dL). The only high-quality study showing clinical outcome benefit was in patients presenting with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.9

Further, it has not been studied in rigorous clinical trials, but it is possible that patients could tolerate a lower RBC transfusion threshold. Consider a study done in young healthy patients, where they removed blood in aliquots of 500 to 900 mL and measured indicators of oxygen delivery (arterial and mixed venous oxygen content, oxyhemoglobin saturation, or arterial blood lactate) before and after each blood aliquot removal.10 At a hemoglobin concentration of 5 g/dL, there were no significant differences in any of the oxygen delivery indicators and only two patients had significant ST changes on the Holter monitor; both resolved spontaneously.

Coming back to the case above, a transfusion was given reflexively in response to a hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL. Instead of using a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL as a strict rule to transfuse, the Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies (AABB) guidelines and experts emphasize the use of clinical judgment with the following factors to be considered prior to transfusion: patient symptoms, clinical status, comorbidities, and individual wishes of the patient. This was not done in the case above and there is no evidence that the benefit of one RBC unit outweighed the risks of transfusion for this patient.

A common diagnosis that deserves particular emphasis when discussing RBC transfusion thresholds is acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

The largest trial included in the AABB guidelines was the REALITY trial.11 In this trial, 668 patients with AMI with or without ST-segment elevations and with a hemoglobin between 7 and 10 g/dL were randomized to a restrictive transfusion strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin concentration ≤8 g/dL) or a liberal transfusion strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin concentration ≤10 g/dL). The primary 30-day outcome was a composite of all-cause death, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization, and it occurred in 11% of the restrictive group and 14% in the liberal group. The difference was not significant. This was true for all subgroups and secondary outcomes. However, in a one-year follow-up study, there were significantly more major adverse cardiovascular events after five months (hazard ratio, 1.71 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.00 to 2.94]) in the restrictive group versus the liberal group.12 Because of this trial and other trials showing mixed results, the 2023 AABB guidelines did not make any recommendations for patients with AMI but did mention that a larger randomized trial, called MINT, was nearing completion.

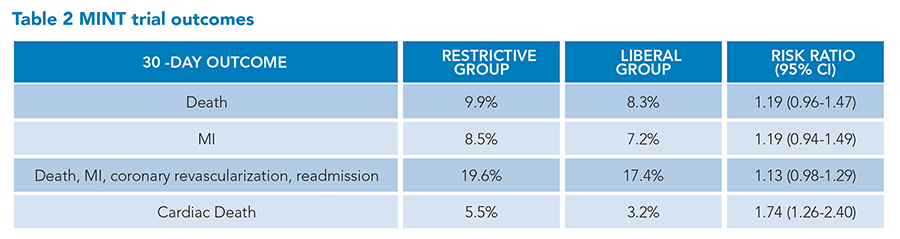

The MINT trial was subsequently published in the December 2023 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.9 This was a well-done, rigorous trial that included 3,504 patients with AMI with or without ST-segment elevations and with hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. Patients were randomized to a restrictive transfusion strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin concentration ≤8 g/dL) or a liberal transfusion strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin concentration ≤10 g/dL).

Patients were ineligible if they had uncontrolled bleeding, were receiving palliative treatment, were scheduled for cardiac surgery, or declined blood transfusion. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day myocardial infarction or death and occurred in 16.9% of patients in the restrictive-strategy group and 14.5% of patients in the liberal-strategy group, risk ratio of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.99-1.34; P=0.07). The secondary outcome results are shown in Table 2. For all secondary outcomes, there were no significant differences but there was a trend in all outcomes towards possible harm in the restrictive strategy group. Moreover, cardiac death was significantly more common in the restrictive strategy group versus the liberal strategy group (5.5% versus 3.2%; risk ratio 1.74 [95% CI, 1.26 to 2.40]). Given the MINT trial results, the long-term outcomes in the REALITY trial, and the exclusion of patients with AMI in previous RBC transfusion studies, an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine written by a member of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s blood products advisory committee recommended a liberal RBC transfusion strategy for patients with AMI.13

Bottom line—RBC transfusion remains a powerful tool in helping our patients. Targeting a lower hemoglobin transfusion threshold of 7 g/dL in most patients is supported by the evidence and is an important improvement in reducing unnecessary transfusions and conserving a valuable resource. However, this transfusion threshold should not replace our clinical judgment and we must continue to rely on the clinical context, risks and benefits, and patient preference when deciding to transfuse patients. Lastly, in patients with acute myocardial infarction, we would support the use of a liberal transfusion strategy targeting a hemoglobin concentration of 10 g/dL.

Bottom line—RBC transfusion remains a powerful tool in helping our patients. Targeting a lower hemoglobin transfusion threshold of 7 g/dL in most patients is supported by the evidence and is an important improvement in reducing unnecessary transfusions and conserving a valuable resource. However, this transfusion threshold should not replace our clinical judgment and we must continue to rely on the clinical context, risks and benefits, and patient preference when deciding to transfuse patients. Lastly, in patients with acute myocardial infarction, we would support the use of a liberal transfusion strategy targeting a hemoglobin concentration of 10 g/dL.

This article is an update of the 2013 article, What Are the Indications for a Blood Transfusion?

Dr. Chang

Dr. Faulk

Dr. Patel

Dr. Dao

Dr. Chang is an associate professor in the division of hospital medicine, the interprofessional education MD thread director, and co-director of the inpatient clinical immersion at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Faulk is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, the director of resident well-being for the internal medicine residency program, and co-director of the internal medicine-advanced clinical rotation for medical students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Patel is an instructor in medicine in the division of hospital medicine and co-director of resident education on hospitalist rotations at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. Dr. Dao is an assistant professor of medicine, a hospitalist, an associate program director for the internal medicine residency program, and the director of OUTmed, an LGBTQIA+ group dedicated to advancing inclusion and education at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., and he serves on SHM’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee.

References

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, et al. Clinical transfusion medicine committee of the AABB. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):49-58.

- Carson JL, Stanworth SJ, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: 2023 AABB International Guidelines. JAMA. 2023;330(19):1892-1902.

- Goel R, Zhu X, et al. Blood transfusion trends in the United States: national inpatient sample, 2015 to 2018. Blood Adv. 2021;5(20):4179-84.

- Hébert PC, Wells G, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409-17.

- Carson JL, Terrin M, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2453-62.

- Hajjar LA, Vincent J-L, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1559-67.

- Mazer CD, Whitlock RP, et al. TRICS investigators and perioperative anesthesia clinical trials group. Restrictive or liberal red-cell transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2133-44.

- Carson JL, Brooks MM, et al. Restrictive or liberal transfusion strategy in myocardial infarction and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2446-56.

- Villanueva C, Colomo A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):11-21.

- Weiskopf RB, Viele MK, et al. Human cardiovascular and metabolic response to acute, severe isovolemic anemia. JAMA. 1998;279(3):217-21

- Ducrocq G, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, et al. Effect of a restrictive vs liberal blood transfusion strategy on major cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia: the REALITY randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(6):552-60.

- Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Lemesle G, et al. One-year major cardiovascular events after restrictive versus liberal blood transfusion strategy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia: the REALITY randomized trial. Circulation. 2022;145(6):486-8.

- Bloch EM, Tobian AAR. Optimizing blood transfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2483-5.