Case

A 30-year-old woman with a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) presents to the hospital with a fever and is found to have Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Soon after admission, she developed significant opioid withdrawal syndrome (OWS) for which she receives 5 mg of oxycodone every six hours. She feels this is inadequate management of the withdrawal and leaves against medical advice (AMA).

OWS is a common sequela of hospitalization for patients with OUD, quickly causing severe discomfort and distress within hours of last use. It is associated with an increased risk of AMA discharge which can increase the risk for mortality from the illness prompting hospitalization in the first place. A 2010 review of almost 2 million discharges at the Veteran’s Administration for AMA discharges found an increased risk at 30 days of re-admission (17.7% versus 11.0%, P <0.001) and death (0.75% versus 0.61%, P = 0.001).1 The exact prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD) among AMA discharges is unclear but likely large, with estimates ranging from 20% to more than 50% of AMA discharges being complicated by SUD.2 This risk increases with daily injection of heroin and decreases with in-hospital use of methadone and social support.3,4 While the need for superior SUD treatment has spurred a call for more addiction-medicine consultants, the pervasiveness of OUD and the acute onset of OWS make management an essential skill for any hospitalist.5

OWS is a common sequela of hospitalization for patients with OUD, quickly causing severe discomfort and distress within hours of last use. It is associated with an increased risk of AMA discharge which can increase the risk for mortality from the illness prompting hospitalization in the first place. A 2010 review of almost 2 million discharges at the Veteran’s Administration for AMA discharges found an increased risk at 30 days of re-admission (17.7% versus 11.0%, P <0.001) and death (0.75% versus 0.61%, P = 0.001).1 The exact prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD) among AMA discharges is unclear but likely large, with estimates ranging from 20% to more than 50% of AMA discharges being complicated by SUD.2 This risk increases with daily injection of heroin and decreases with in-hospital use of methadone and social support.3,4 While the need for superior SUD treatment has spurred a call for more addiction-medicine consultants, the pervasiveness of OUD and the acute onset of OWS make management an essential skill for any hospitalist.5

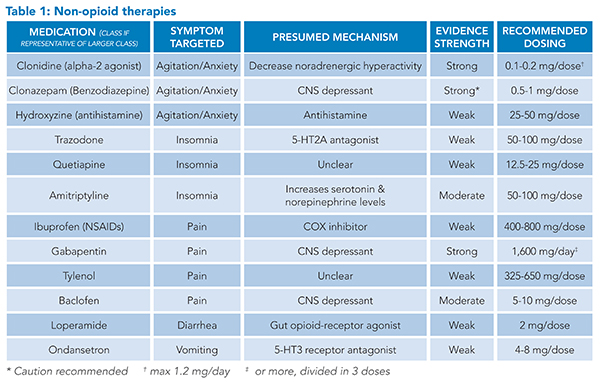

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) such as buprenorphine and methadone constitute the mainstay of treatment for OWS and OUD. The withdrawal period is the preferred time for initiation of buprenorphine, and the efficacy of these medications on OUD outcomes is well documented.6 Non-opioid therapies are also available as additional medications to address the distressing symptoms of OWS and can be used in conjunction with MOUD initiation, titration, and maintenance. Some scenarios may also exist in which a non-opioid strategy may be relied on to treat OWS. Hospitalists can be more effective in managing OWS with the knowledge of these medications and their efficacy.

Overview of the data

OWS is characterized by multiple, frequently distressing symptoms. These symptoms can involve multiple organ systems including neuropsychiatric, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal, each with its unique management options.

Neuropsychiatric: Neuropsychiatric symptoms in OWS include anxiety, agitation or irritability, and insomnia.

Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists, such as clonidine and lofexidine, are the cornerstone of non-opioid management of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of OWS. Studies have shown changes in norepinephrine levels during opioid dependence, as well as an increase in the chemical during opioid withdrawal.7 The sensitivity of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors changes with opioid use, and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists appear to alleviate some of the symptoms of withdrawal by centrally decreasing non-adrenergic hyperactivity.7,8

Clonidine is the most widely used alpha-2 adrenergic agonist with the most research to date. However, common side effects include sedation, dry mouth, and most notably, hypotension.8 Hypotension must be carefully monitored especially in the setting of other common symptoms of opioid withdrawal, such as vomiting and diarrhea.

Lofexidine is a newer alternative alpha-2 adrenergic agent and is now the only non-opioid, U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for the treatment of OWS in adults. It has a similar side effect profile to clonidine though with fewer hypotensive episodes.8 Lofexidine has been shown to significantly improve OWS symptoms with a generally acceptable safety profile.9 Few studies have compared the two head-to-head, but lofexidine use may be limited by cost. Other medications with alpha-2 adrenergic properties include guaifenesin and tizanidine, both of which are not widely used in OWS.

Benzodiazepines are also available for use in neuropsychiatric symptom management. Generally, benzodiazepines with a slower onset of action are more favorable than those with a faster onset given their lower abuse potential. For this reason, clonazepam and oxazepam are preferred, and it is recommended that diazepam and alprazolam be avoided.10 It is important to keep in mind that opioid and benzodiazepine co-dependence exists. One study found that of those entering opioid detoxification programs, 25% had concurrent benzodiazepine dependence, with the primary indication being treatment of anxiety.11 Because of this risk, the authors do not recommend initiation of benzodiazepines for neuropsychiatric symptom management without careful monitoring and mindfulness of the risk of co-dependence.

Other options for anxiety management include antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine.10 There is limited evidence, with concern for study bias, that hydroxyzine is as effective as benzodiazepines with similar tolerability if used to treat generalized anxiety disorder, although it can lead to greater drowsiness.12

For the treatment of insomnia, trazodone, doxepin, zolpidem, and quetiapine can all be considered.10 Dopamine, serotonin, cannabinoid, orexin (hypocretin), and glutamate systems contribute to OWS as evidenced by both animal and human studies.13 Quetiapine works on the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems and has been shown to improve multiple withdrawal symptoms, including insomnia, craving, and pain.13 Given the above concerns regarding benzodiazepines, amitriptyline is just as effective as lorazepam at insomnia management in opioid withdrawal.14

Musculoskeletal: Pain is a common feature of OWS, but it is crucial to distinguish the diffuse myalgias and bone pains of OWS from any focal pain that may be related to a patient’s presenting illness and to treat acute pain appropriately. For patients with pain directly related to OWS, several medication classes are available for the hospitalist to use.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and ketorolac, are often looked to as non-opioid options to manage pain in the setting of withdrawal. Limited data exist in human populations to describe their efficacy in doing so; however, several animal models have demonstrated NSAID administration ameliorates pain and other withdrawal symptoms in rats who underwent induced withdrawal.15,16 While difficult to extrapolate to humans, NSAIDs are a valuable class of medications available to clinicians to address pain in the absence of contraindications. Ideal agent and dose are not well defined.

Gabapentin can be effective in ameliorating pain and other withdrawal symptoms in patients undergoing both opioid-replacement therapy and withdrawal. The medication appears to have a dose-dependent response. In one study investigating varying doses of gabapentin in a population undergoing supervised methadone withdrawal, 1,600 mg per day was associated with decreased pain and withdrawal symptoms compared to 900 mg per day and to placebo; the lower dose, 900 mg per day, was no better than placebo.17 In this study, the gabapentin dose was started at 800 mg per day and titrated to 1,600 mg per day over three days, then continued for three weeks. Gabapentin appears to be effective when started and up-titrated quickly.

Baclofen, another GABAergic medication, has been successfully used in several non-opioid drug-withdrawal studies.18,19 It appears to have favorable impacts on general withdrawal symptoms as well as depressive symptoms.18 Data on its use specifically for pain treatment in the setting of withdrawal is limited, however. Given spasms and other muscle-related pains are frequently reported in withdrawal, its targeted use for muscular pain makes intuitive sense.

While acetaminophen is commonly included in opioid withdrawal protocols, data are limited on its use for pain experienced by OWS.

Gastrointestinal: Gastrointestinal symptoms are commonly experienced in OWS. These can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.

Loperamide is frequently used for diarrhea related to OWS and works by inhibiting intestinal motility and reducing fluid and electrolyte losses.20 Loperamide binds to opioid receptors in the intestinal wall, a property that has led researchers to investigate the medication as a primary method of opioid detoxification in combination with proton pump inhibitors.21

Ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, can be beneficial in the treatment of nausea, given serotonin’s role in OWS. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been shown to improve a myriad of withdrawal symptoms including pain and hot flashes, which can be relieved further with co-administration of hydroxyzine.22,23

Recent data has shown that mirtazapine, both an antihistamine and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, can be used to manage symptoms from nausea and diarrhea to anxiety and insomnia.24

Caution must be taken with loperamide and most antinausea medications, including ondansetron and promethazine, as they can cause QTc prolongation or exacerbate the QTc prolongation from other medications used for OWS.25

Application of the data to the original case

The patient returned to the hospital three days later because of worsening fevers and new swelling in her lower extremities. She is admitted and immediately started on methadone, clonidine, loperamide, hydroxyzine, and ondansetron for symptom management in addition to appropriate antibiotics. Her non-opioid medications for OWS provide a bridge for symptom management during the up-titration of her methadone and she remains in the hospital for treatment of her life-threatening infection.

Bottom line

OWS is a common complication of hospitalization for patients with OUD and frequently contributes to AMA discharges and concomitant morbidity and mortality. While MOUDs are the mainstay of long-term treatment, familiarity with and understanding of appropriate use for the many non-opioid medications for the management of OWS is an essential skill for hospitalists to improve symptoms and outcomes.

Dr. Clark

Dr. Wood

Dr. Pizanis

Dr. Imber

Dr. Clark is a PGY3 in internal medicine and a member of the hospitalist training track and of the integrative medicine track at the University of New Mexico (UNM) in Albuquerque. Dr. Wood is a PGY3 in internal medicine and a member of the hospitalist training track at UNM in Albuquerque. Dr. Pizanis is an associate professor within the department of internal medicine’s division of hospital medicine, and co-director of the hospitalist training track, at UNM in Albuquerque. Dr. Imber is an associate professor within the department of internal medicine’s division of hospital medicine, and the executive director of assessment and learning for undergraduate medical education, at UNM in Albuquerque.

Quiz:

A 33-year-old woman is admitted after a car accident resulting in multiple traumatic fractures. After the repair of her fractures, and despite the provision of opioid analgesics, the patient complains of persistent severe pain and opioid withdrawal symptoms, including anxiety, on hospital day three. What should the next step for the hospitalist be?

A. Reassure the patient that opioid withdrawal is not life-threatening

B. Increase opioids for pain and withdrawal and add clonidine for anxiety

C. Add hydroxyzine to her current pain regimen

D. Initiate alprazolam for anxiety in addition to her current pain regimen

Correct option: B. The patient has a high tolerance for opioids and the experience of withdrawal while on opioid medication implies that she is not receiving nearly as much as she is used to using outside of the hospital. Given that she has a clear cause of acute pain, treatment of her pain and withdrawal symptoms should be prioritized and transition to safer MOUD should be pursued once her initial symptoms are improved.

Incorrect options:

A. Reassurance alone is not sufficient to manage the patient’s symptoms and may lead to AMA discharge.

C. While hydroxyzine has a role in managing anxiety related to OWS, it alone will not be sufficient to manage the patient’s pain.

D. Benzodiazepines can improve anxiety related to OWS, though the risk of co-dependence should caution against their use as first-line agents. Additionally, short-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam should be specifically avoided as they have an increased risk of addiction.

References

- Glasgow JM, Vaugh-Sarrazin M, et al. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-9.

- Anis AH, Sun H, et al. Leaving hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):633-7.

- Ti L, Milloy M-J, et al. Factors associated with leaving hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141594.

- Ti L, Ti L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53-9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302885.

- Calcaterra SL, McBeth L, et al. The development and implementation of a hospitalist-directed addiction medicine consultation service to address a treatment gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1065-72.

- Wakeman SE, LaRochelle MR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

- Maldonado R. Participation of noradrenergic pathways in the expression of opiate withdrawal: biochemical and pharmacological evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21(1):91-104.

- Gowing L, Farrell M, et al. Alpha2-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(5):CD002024. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002024.pub5

- Gorodetzky CW, Walsh SL, et al. A phase III, randomized, multi-center, double blind, placebo controlled study of safety and efficacy of lofexidine for relief of symptoms in individuals undergoing inpatient opioid withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;176:79-88.

- Sigmon SC, Bisaga A, et al. Opioid detoxification and naltrexone induction strategies: recommendations for clinical practice. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(3):187-99.

- Stein MD, Kanabar M, et al. Reasons for benzodiazepine use among persons seeking opioid detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;68:57-61.

- Guaiana G, Barbui C, et al. Hydroxyzine for generalised anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(12):CD006815. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006815.pub2

- Dunn KE, Huhn AS, et al. Non-opioid neurotransmitter systems that contribute to the opioid withdrawal syndrome: a review of preclinical and human evidence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2019;371(2):422-52.

- Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Amitriptyline vs. lorazepam in the treatment of opiate-withdrawal insomnia: a randomized double-blind study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998 Mar;97(3):233-5.

- Verster JC, Scholey A, et al. Functional observation after morphine withdrawal: effects of SJP-005. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;236(6):1449-60.

- Dunbar SA, Karamian I, et al. Ketorolac prevents recurrent withdrawal induced hyperalgesia but does not inhibit tolerance to spinal morphine in the rat. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(1):1-6.

- Salehi M, Kheiriabadi GR, et al. Importance of gabapentin dose in treatment of opioid withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):593-6.

- Assadi SM, Radgoodarzi R, et al. Baclofen for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial [ISRCTN32121581]. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:16.

- Ahmadi-Abhari SA, Akhondzada S, et al. Baclofen versus clonidine in the treatment of opiates withdrawal, side-effects aspect: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(1):67-71.

- Regnard C, Twycross R, et al. Loperamide. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(2):319-23.

- Garhy, MA, Williams JJ, et al. Novel opioid detoxification using loperamide and P-glycoprotein inhibitor. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2019;23(4):19-24.

- Erlendson MJ, D’Arcy N, et al. Palonosetron and hydroxyzine pre-treatment reduces the objective signs of experimentally-induced acute opioid withdrawal in humans: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(1):78-86.

- Chu LF, Liang D-Y, et al. From mouse to man: the 5-HT3 receptor modulates physical dependence on opioid narcotics. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009;19(3):193-205.

- Lalani, E, Menon R, et al. Mirtazapine: a one-stop strategy for treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms. Cureus. 2023;15(8). e43821. doi: 10.7759/cureus.43821.

- White CM. Loperamide: a readily available but dangerous opioid substitute. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59(9):1165-9.