When the space shuttle Challenger exploded in the sky in 1986, a group of engineers’ fears had come true: They had known a critical failure was possible at the low temperatures that were seen around the time of the launch, and that the launch should have been scrubbed, but not enough engineers spoke up. The launch—and the tragedy—were allowed to come to pass.

When the space shuttle Challenger exploded in the sky in 1986, a group of engineers’ fears had come true: They had known a critical failure was possible at the low temperatures that were seen around the time of the launch, and that the launch should have been scrubbed, but not enough engineers spoke up. The launch—and the tragedy—were allowed to come to pass.

One reason—a group of experts said at SHM Converge 2023—was that they had no “psychological safety” allowing questions and dissent. So their opinions were drowned out by their superiors and administrators at NASA.

Creating this environment of psychological safety is also crucial to fostering a robust learning environment in hospital medicine, said the panelists, Rebecca Dougherty, MD, MSEDc, principal advisor for Northwell Health’s Center for Equity of Care in New Hyde Park, N.Y., Janice John, DO, MS, MPH, assistant dean for integrated medical education at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and Nayla Idriss, MD, associate chief of hospital medicine at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York.

Believing you won’t be punished or humiliated for offering ideas or asking questions in the clinical environment is crucial for a healthy work and education atmosphere, experts said here in a session at SHM Converge.

Dr. Dougherty said most hospitalists, especially early in their careers, have probably been in situations “when you had a question but no one else seemed to be asking that question so you remained silent. You thought you should know the answer to the question and decided you’d just figure it out later.”

Psychologists call this phenomenon oppression management, she said.

“We want to be seen as knowledgeable, competent, and positive,” she said. “However, this can come at the expense of speaking up when it’s critically necessary and it means that we can lose key moments of learning and growing.”

Psychological safety is the shared belief on a team that there will be no punishment or humiliation despite having a different idea, Dr. John said.

“This is really key to having an environment where there’s learning and innovation,” she said. “And that’s what we all want as hospitalists.”

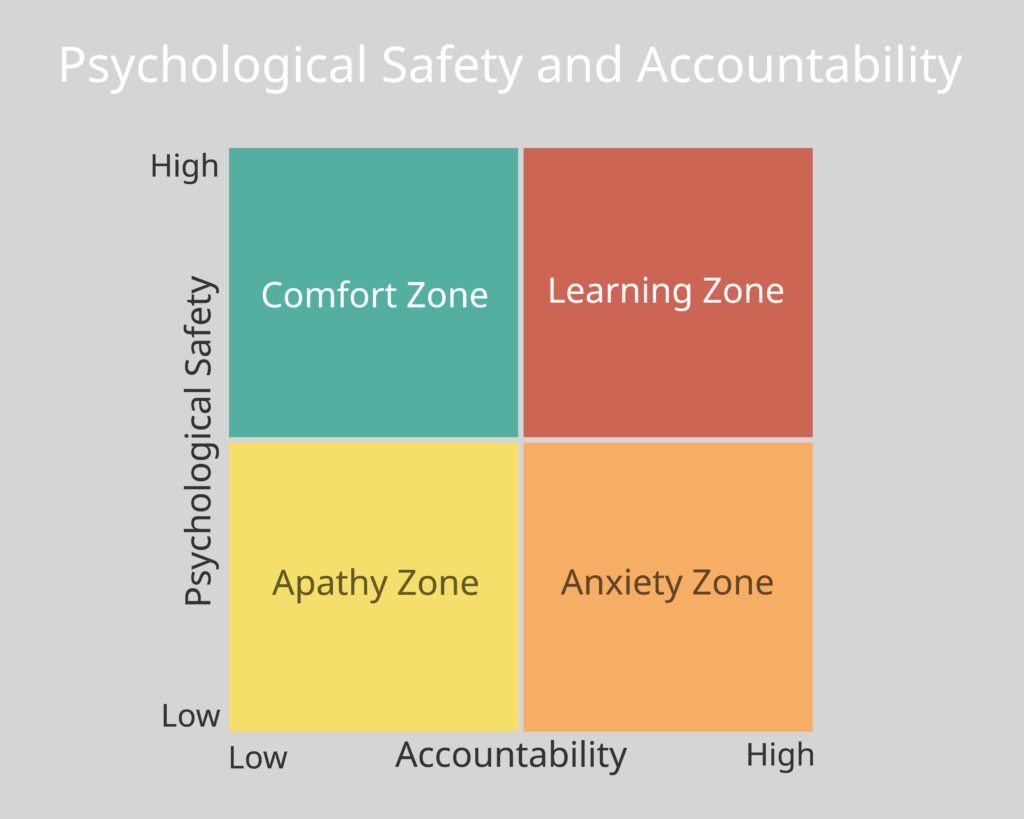

The ideal environment for learning is when there is a high level of psychological safety but also high performance pressure. If the level of psychological safety is high but the performance pressure is too low, that makes for a comfort zone. If the psychological safety level is too low while the performance pressure is high, that creates an anxiety-filled atmosphere. So it’s important to get both right, Dr. John said.

Dr. Idriss said that people want to feel included—that they are a valuable piece woven into the team. “We need to have a sense of belonging,” Dr. Idriss said. “As humans, we have a powerful drive for feeling a sense of belonging.”

In her book “The Fearless Organization,” Amy Edmondson writes about three steps toward creating this psychologically safe environment.

1. Set the stage. Leaders should “set the stage” by clearly defining the work they’re referring to, articulating why this work matters, and talking often about what is at stake in this work.

“Everybody needs to feel a sense of value and respect that they’re actively participating in the care of their patient,” Dr. Idriss said.

Team leaders also need to be very clear in setting expectations, such as: when English isn’t the preferred language of a patient, a translator is always used.

2. Invite participation. “Be explicit about the fact that you are fallible. Use words like, ‘I could miss something, I haven’t had a patient like this,’” Dr. John said.

Questions should be asked with a genuine sense of curiosity—and not because you are trying to elicit a pre-determined answer, she said.

“It seems so common sense, but it’s a radically different way of asking a question,” she said.

It’s also vital that everybody—and not just a few senior people—have “space on the team for inquiry,” she said.

There should also be a structure in place so that participating in discussions is invited. At the end, leaders could say, “What have we forgotten?” or, “What questions do we have?”

3. Respond to participation productively. Leaders need to express appreciation, and thank people for bringing up their ideas, Dr. Dougherty said.

They should also “destigmatize failure,” she said.

“It’s very important to acknowledge to the learners or whoever is on the team that mistakes happen not as the result of bad people, but typically because of systems that are in place that didn’t prevent the error,” Dr. Dougherty said.

Audience members formed pairs to discuss a hypothetical scenario in which a patient is a non-English speaker, and an intern acknowledges that a translator wasn’t used. One audience member said that at her center, family members of non-English speakers are commonly used to translate, against institutional policy. She said that explaining the reason for the rule against this—patient safety, and the difficulty of a family member to have to report bad news—can be an effective way to go about the discussion.

“People are less likely to cut corners when they understand the ‘whys,’” she said.

Dr. Idriss said that, in the end, the point is “that we all recognize that the work we’ve done to foster a psychologically safe environment leads to better learning opportunities, increased innovation, and improved patient safety.”

Tom Collins is a medical writer in South Florida, who has written about everything from lethal infections to thorny ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He gathers health news from around the globe and lives in West Palm Beach.