As our discussion about discharge ended, Ms. Jones, stooped, her thin grey hair pulled back, and moved slowly toward her husband’s hospital bed. Gently, she stroked his head and said, “We will find a way through this; won’t we, Henry?” His fragility and his cancer diagnosis couldn’t dampen the 60 years of love that warmed the room; he opened his eyes and smiled.

Before leaving the room, I said, “I am so privileged to do this work and to be involved in your care at this important time. Thank you.” A wave of emotion flowed through my body as I walked out of the room and I thought to myself, “It is a privilege to do this work. God, I love it!”

For years, I had been hearing about how “gratitude is good for us” but my scientific mind wondered if this was just ‘woo-woo’ talk. Instead, I found an incredibly robust body of evidence and when I learned how to apply it, I found my experience of work transformed. Let me share with you what I learned about gratitude and how it can help us find profoundly rewarding emotional experiences as we move through our days as hospitalists.

For its first 100 years, the field of psychology almost exclusively focused on psychopathology—what is wrong with the mind. Then in the ‘90s, a group of young California-based researchers started investigating healthy mental states, and the field of positive psychology was born. One of them was Robert Emmons, PhD, at the University of California, Davis. He convinced a group of prominent theologians to spend a few days with him to share how they conceived of gratitude, why it is at the heart of all our great religions, and how it might help us.

A few years later, Dr. Emmons published his seminal paper on gratitude journaling where participants were asked to write down three things, they were grateful for three times a week for six weeks. He found that going out six months people reported improved affect, optimism, and relationships with their partners. People also reported exercising more and having fewer physical complaints.

Since then, literally hundreds of other studies have confirmed and expanded on the psychological and physical benefits of gratitude. Gratitude practices lead to better sleep, better eating habits, and improved self-efficacy and compliance. Incorporating gratitude into cardiac rehab can decrease blood pressure, increase heart rate variability, and lower inflammatory markers.

The Roman philosopher Cicero called gratitude “the mother of all virtues,” it turns out for good reason. People who are reported to be more grateful are also thought to be kinder, wiser, and more generous than their peers. And grateful people are more resilient as well. Psychologists believe gratitude evolved as a social glue for a species that completely relies on teamwork for survival.

They see gratitude leading to a “virtuous cycle” where:

- We recognize something of value coming from beyond ourselves.

- We receive the gift and acknowledge the source.

- The positive emotion associated with this process inspires us to “pay it forward” and thus the cycle continues.

So why are we not all overflowing with gratitude? Also key to our survival is finding threats. We all have an inherent negativity bias. We are constantly seeing things that are not going well or which we might improve upon. It’s called hedonic adaptation. We quickly stop seeing what is going well and focus on what is not. This negativity bias blinds us to all that is going right every day.

Over the last several years I have been working on ways to help my colleagues discover more gratitude while caring for patients in the hospital. Using resources from my colleagues at Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, I came up with a list of six things we can do as hospitalists to experience more gratitude.

6 ways to find more gratitude at work

- Appreciate all that is going right! We don’t have to let humankind’s negativity bias rule the day. So much goes well in our lives we should recognize it. Water flows from the tap, lights go on, and the fridge is full of food from around the world. And we have medicines and equipment that were unimaginable for almost all human history. We should be grateful each time well-trained staff helps our patients, a procedure goes smoothly, or we receive payment for work with patients who without aid could not afford health care.

- Slow down for just a few seconds. That’s all it takes for a deep breath to decrease our sympathetic tone. With the parasympathetic nervous system activated, the vagus nerve can create more visceral, felt sensations when we experience emotions like gratitude. When we feel emotions more profoundly, we have a greater appreciation for them and continue to seek them out.

- Remember, the real stories in health care are those of the patients. It is natural to focus on the role of the practitioner in health care because that is what we ar

e doing. And in fact, we are doing more, but the real story is how our patients and their families cope with failing bodies and their mortality. This is the stuff of great dramas and our front-row seat to moments that define the human condition should be seen as a gift.

e doing. And in fact, we are doing more, but the real story is how our patients and their families cope with failing bodies and their mortality. This is the stuff of great dramas and our front-row seat to moments that define the human condition should be seen as a gift. - Say thanks like you mean it. It is easy to get in the habit of offering a “customer service-like” thanks. Instead, earnestly say, “It is truly a privilege to be involved in your care at this important time in your life. Thank you.” Or come up with a line that works for you. When you say it like you mean it, you will mean it and you will feel it strongly in your mind and body.

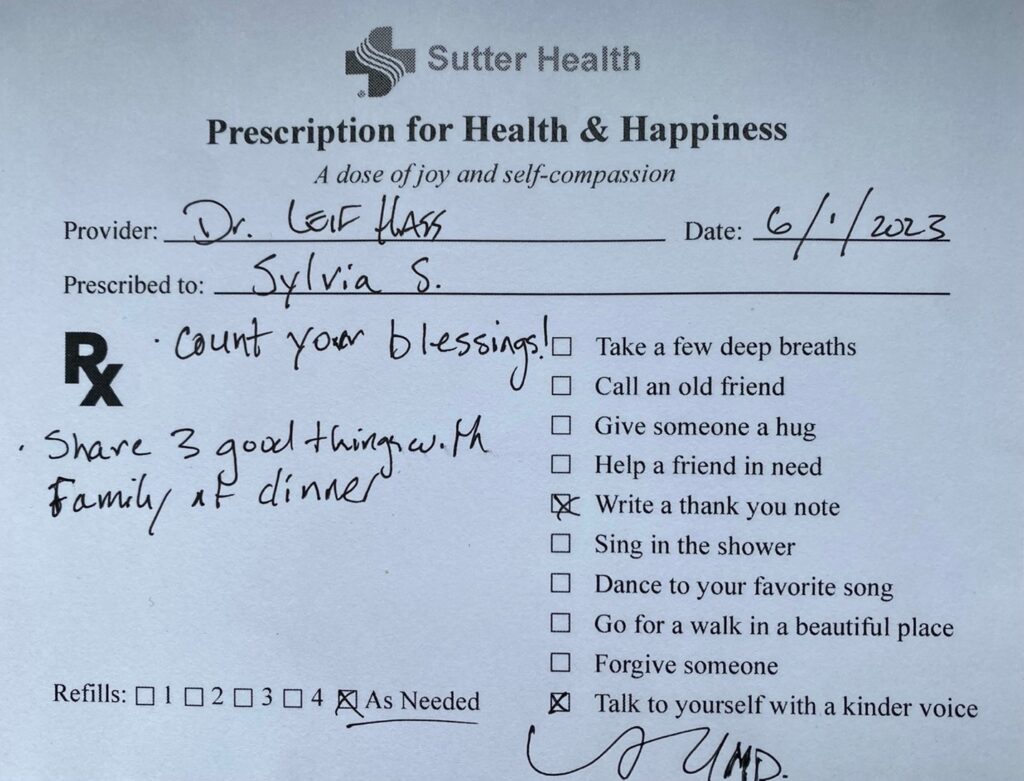

- Prescribe it! For our patients, gratitude can be a powerful medicine as they try to navigate the course of their illnesses. At discharge, I regularly prescribe a gratitude practice, along with statins, diuretics, and antibiotics. I honestly think it can be more helpful than many of the pills we prescribe. And caring in this more personal way generates a sense of connection that benefits both parties. Personally, teaching about gratitude might be the most important part of my own gratitude practice. Give it a try.

- See medicine as sacred work. Sacred means beyond the ordinary. Bringing people back from the brink of death and attending to dying patients. Seeing the love, courage, and determination of patients and families as the body fails; ours is extraordinary work. Seeing the sacred nature of our work can turn it into a spiritual practice and an unending source of gratitude.

People use the term “gratitude practices” because practice helps. The more we flex our gratitude muscles—the more we strengthen positive neural pathways and in turn, let atrophy unhelpful ones—the better our health and outlook. We make practices of counting steps and carbs. A good scientific argument could be made that in terms of overall health and well-being investing in a gratitude practice is a better strategy. And it all can be done with little added time. Mostly, what is needed is presence of mind or awareness.

Beyond what I suggest above, there are many other ways to develop a more grateful outlook. Journaling may be the most powerful practice because of the way writing works on our neural processes. An easier practice is “Three Good Things.” At dinner, share three good things that happened during your day; it is a great way to draw kids into conversation, too. You can also make a habit of thanking your hardworking nursing and ancillary colleagues for all they do—even just showing up to their tough jobs!

Hospital medicine is really tough work: time pressures, bureaucracies, people trying to die! We need all the help we can get to find purpose, meaning, and beauty in the work so we can thrive, and give our patients the care they deserve. My practice of gratitude puts me in a mental space to do this; it can be for you, too.

So, thank you for all the love and hard work you give your patients and staff. Thanks for caring about the most vulnerable members of our communities.

Please reach out if you want to learn more about these prescriptions [email protected].

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter East Bay Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., a member of the clinical faculty at the University of California, Berkeley-UC San Francisco joint medical program, and an adviser on health and health care at the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter East Bay Medical Group in Oakland, Calif., a member of the clinical faculty at the University of California, Berkeley-UC San Francisco joint medical program, and an adviser on health and health care at the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

Thank you for reminding us to pause and give thanks!