This is an update of our 2015 article on cavitary lung lesion.1

Case

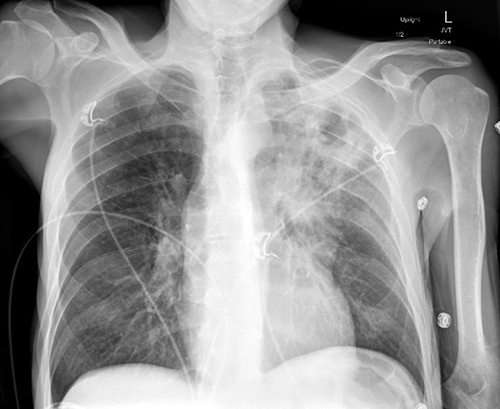

A 60-year-old man with alcohol use disorder presented to the hospital with fatigue, chest pain, and productive cough for two weeks. Additionally, he endorsed a 20-lb weight loss over the previous month which he attributed to a poor appetite. He lived in the southwestern U.S. and had no recent travel. His initial chest X-ray demonstrated a 3.4-cm left upper lobe cavitary lesion (Figure 1).

Overview

Hospitalists frequently encounter patients with cavitary lung lesions on chest imaging and are often faced with initiating their early workup and management. Having a strategy for the initial diagnostics and therapeutics as well as a plan for pre-consultation can assist in streamlining workup.2 Additionally, hospitalists are frequently involved in establishing the initial surveillance strategy for cavitary lung lesions upon discharge, and developing a mental framework for follow-up can assist in optimizing the outpatient transition of care.

A cavitary lung lesion is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule. It is further characterized by thick walls of greater than 4 mm.3,4 The differential for these lesions is broad and includes both infectious and non-infectious causes.

Infectious causes

Figure 1: Chest X-ray of a hospitalized patient demonstrating a left upper lobe cavitary lung lesion.

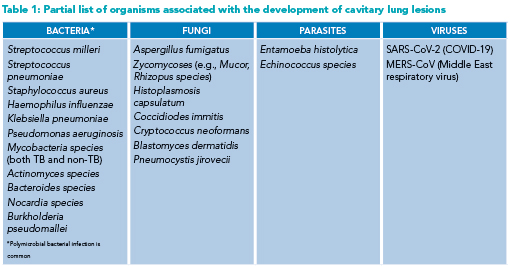

The organisms known to cause cavitary lung lesions are many and include bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses (Table 1). Principal among them for consideration, particularly from an infection-control standpoint, is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lung abscesses and necrotizing pneumonias, subsets of cavitary lung lesions, carry another unique spectrum of causative organisms. Anaerobic and microaerophilic streptococci (e.g., Streptococcus milleri) make up the majority of identified organisms, and polymicrobial infection is commonly encountered.5,6 Other non-tuberculous mycobacterium such as M. abscessus and M. avium also cause cavitations. Notable aerobic organisms occasionally encountered include Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae.6

Fungi and parasites, while rarer than bacterial causes, require significantly different treatment regimens. Aspergillus fumigatus in its invasive form is known to occupy preexisting lung cavities and is identifiable by the presence of a fungal ball (aspergilloma) within the lung cavity.7 Other endemic fungi (e.g., Histoplasmosis capsulatum) have been linked to cavitary lung lesion development.8

Lung cavitation in the setting of COVID-19 infection

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, several cases of lung cavities in the setting of COVID-19 infection have been reported. In a single-center study reporting on the radiographic appearance and clinical outcomes of 689 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, 3.3% of patients developed lung cavitation. Cavity sizes ranged from 30 to 100 mm in diameter and were solitary or multiple. Bacterial and fungal coinfections were noted in some but not all patients. Notably, cavitations appeared on subsequent and not initial chest imaging in all patients, suggesting lesions represented a delayed complication of COVID-19 infection.9 Mechanisms of cavitation are not fully known but autopsy data have suggested a mixture of thrombotic vascular occlusion accompanied by liquefying necrosis contributing to cavity development.10 Lung cavitation in the setting of COVID-19 pneumonia appears to be a poor prognostic indicator, with death occurring in 50% of patients in the aforementioned case series.9

Non-infectious causes

Several non-infectious causes of lung cavitations exist and should be considered in the differential. These include malignant, rheumatologic, vascular, and infiltrative conditions. A principal consideration of a lung cavity is malignancy. Both primary lung cancers and metastatic cancers are known to cause cavitations, with cancers of squamous cell origin being the cell type most known to cavitate.11 Several rheumatologic conditions have also been linked to lung cavitation. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis are all known to cause cavitation. Other less common causes of lung cavitation include pulmonary embolism (usually resulting from pulmonary infarction), Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis.4

Several non-infectious causes of lung cavitations exist and should be considered in the differential. These include malignant, rheumatologic, vascular, and infiltrative conditions. A principal consideration of a lung cavity is malignancy. Both primary lung cancers and metastatic cancers are known to cause cavitations, with cancers of squamous cell origin being the cell type most known to cavitate.11 Several rheumatologic conditions have also been linked to lung cavitation. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis are all known to cause cavitation. Other less common causes of lung cavitation include pulmonary embolism (usually resulting from pulmonary infarction), Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis.4

Patient characteristics

A focused pulmonary history is essential in guiding the workup. Conditions such as substance use disorders, seizure disorders, or swallowing deficits put patients at risk for aspiration, which is the most common cause of pulmonary abscesses. Immunosuppression, particularly neutropenia or hematologic malignancies, greatly raises the likelihood of infections from fungi and atypical bacteria. Carcinogens such as tobacco smoke or occupational exposure increase the primary lung cancer risk. Finally, circumstances such as travel to endemic regions, homelessness, incarceration, or sick contacts increase the risk of atypical infections such as Mycobacteria or coccidioidomycosis.

A focused pulmonary history is essential in guiding the workup. Conditions such as substance use disorders, seizure disorders, or swallowing deficits put patients at risk for aspiration, which is the most common cause of pulmonary abscesses. Immunosuppression, particularly neutropenia or hematologic malignancies, greatly raises the likelihood of infections from fungi and atypical bacteria. Carcinogens such as tobacco smoke or occupational exposure increase the primary lung cancer risk. Finally, circumstances such as travel to endemic regions, homelessness, incarceration, or sick contacts increase the risk of atypical infections such as Mycobacteria or coccidioidomycosis.

Imaging characteristics

While establishing a diagnosis from radiographic findings alone is unlikely, certain imaging cues can narrow the differential. Apical lung lesions are more commonly seen with tuberculosis and primary lung cancer, while the lower lobes are more often involved in necrotic pneumonias, septic emboli, or metastatic disease. Multiple cavitary lesions are more common in autoimmune disease, atypical infections, or metastatic cancer, whereas solitary lesions are more common with primary lung cancer or lung abscesses. Cavity-wall thickness has also been proposed as an effective tool, with thicknesses greater than two cm highly associated with malignancy and benign lesions frequently having thin walls of less than seven mm. Lastly, findings such as associated consolidation or tree-in-bud nodules are more likely to be infectious, while a visible mass within a cavity is almost pathognomonic for an aspergilloma.

Initial diagnostics

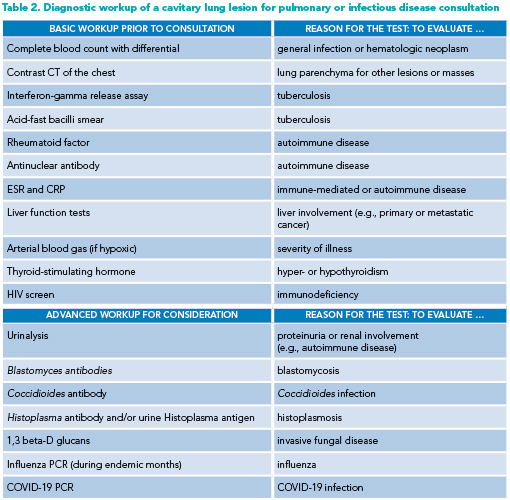

Prior to infectious disease or pulmonary consultation, the hospitalist clinician should obtain several tests as part of the initial workup. Additional, more advanced testing may be ordered depending on the likelihood of certain diagnoses on the differential (see Table 2 for suggested pre-consultation evaluation).

Bronchoscopy or biopsy?

While often the etiology of a cavitary lesion can be determined through a focused history and non-invasive workup, certain entities require a more invasive workup with bronchoscopy or percutaneous biopsy. If malignancy is of primary concern, consultation with a pulmonologist should occur to help determine the feasibility of a bronchoscopic biopsy or if interventional radiology is required. Certain patients such as those with hematologic malignancies or immunosuppression are at higher risk for atypical infections and may benefit from earlier bronchoscopy to guide antimicrobial therapy.

What to do at hospital discharge

The frequency of surveillance imaging for cavitary lung lesions will vary based on the etiology. In the case of malignancy, it is determined by cell type, initial staging, and treatment plan. A common question for hospitalists, however, is what the appropriate follow-up and monitoring should be, specifically for lung abscesses. Patients should typically receive an empiric trial of antibiotics before more invasive measures are attempted, as approximately 90% will improve with antibiotic therapy alone.12,13 Resolution on imaging may take several weeks or months and serial chest imaging should be obtained to monitor progress through the course of treatment.1,6 A strategy for imaging can include a repeat CT four to six weeks into treatment with subsequent imaging depending on clinical and radiographic status.

Should a lung abscess fail to improve with conservative therapy in the expected timeframe (or if the patient demonstrates clinical deterioration), pulmonology consultation is warranted for further diagnostic workup, typically with bronchoscopy to obtain further culture data and look for obstruction.13 Failure to improve despite an adequate trial with appropriate antibiotics may necessitate percutaneous drainage, endobronchial drainage, or, rarely, surgical resection. Depending on abscess location and local expertise, pulmonology, interventional radiology, and/or thoracic surgery consultations may be necessary to guide the next steps in management.1

Back to the case

After initial diagnostics, the patient was started on empiric antibiotics and discharged home with outpatient imaging follow-up. Subsequent chest imaging demonstrated resolution of cavitation and the cause was attributed to aspiration.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are central to driving the care for hospitalized patients with cavitary lung lesions found on imaging.

Quizz

A 66-year-old man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis who is experiencing homelessness presents to the emergency department with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion. Which of the following is the best next step in management?

A. Chest CT with contrast

B. Image-guided biopsy of the lesion

C. Initiation of piperacillin-tazobactam

D. Obtain antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing

E. Sputum smear for acid-fast bacilli

Correct option: Choice A. Chest CT with contrast is the best next step in management; it will allow for the characterization of the cavitary lesion, including whether other masses or lung pathology are present within the lungs.

Choice B. An image-guided biopsy is typically obtained in cases of suspected neoplasm. Although this may be a reasonable diagnostic test later in the workup, it’s not the best next step. If infectious, a biopsy could cause seeding of infection in other areas of the lung and would not significantly change management.

Choice C. Initiation of piperacillin-tazobactam may be prudent if the cavitary lung lesion is suspicious for bacterial infection, which is highly likely in this case. But a more appropriate antibiotic choice would be ampicillin-sulbactam given the low likelihood of a pseudomonal infection inducing the cavitary lung lesion.

Choice D. Ordering an ANA test may be reasonable in this instance although there is nothing specifically worrisome in the stem for an autoimmune etiology. If the patient had a malar rash (or other signs of lupus), this would increase the likelihood of an autoimmune cause. This patient likely has an infection.

Choice E. Sputum smear for acid-fast bacilli is a reasonable choice as it is important to rule out tuberculosis, especially given the history of experiencing homelessness. A chest CT, however, would be a more appropriate next step before an acid-fast bacilli smear is obtained.

Dr. Pizanis

Dr. Wurzburger

Dr. Rendón

Dr. Dean

Dr. Pizanis is an associate professor and section chief in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Wurzburger is an assistant professor and associate program director of internal medicine residency at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Rendón is an academic hospitalist and associate professor in internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M. He is also the assistant clerkship director of the internal medicine clerkship, director of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, and gastrointestinal curricula in the first two years of medical school, and co-director of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine phase I curriculum committee. Dr. Dean is an assistant professor in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M.

References

- Pizanis C, et al. What is the best approach to a cavitary lung lesion? The Hospitalist website. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/122550/what-best-approach-cavitary-lung-lesion/4/. Published March 3, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2023.

- Esquivel EL, Rendon PA. 10 questions you should consider for specialist consultations. The Hospitalist website. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121853/10-questions-you-should-consider-specialist-consultations. Published March 9, 2016. Accessed September 7, 2023.

- Hansell DM, et al. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-52.

- Bartlett, JG. The role of anaerobic bacteria in lung abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):923-5.

- Kuhuajda I, et al. Lung abscess-etiology, diagnostic, and treatment options. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(13):183.

- Kousha M, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Resp Rev 2011;20:156-74.

- Salzer HJF, et al. Diagnosis and management of systemic endemic mycoses causing pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2018;96:283-301.

- Zoumot Z, et al. Pulmonary cavitation: an under-recognized late complication of severe COVID-19 lung disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(24). doi:10.1186/s12890-020-01379-1

- Kruse JM, et al. Evidence for a thromboembolic pathogenesis of lung cavitations in severely ill COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16039. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95694-0

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5:523-30.

- Takayanagi N, et al. Etiology and outcome of community-acquired lung abscesses. Respiration. 2010;80(2):98-105.

- Wali SO. An update on the drainage of pyogenic lung abscesses. Ann Thorac Med. 2012;7(1):3-7.