In our current post-COVID-19 world, few topics come up more frequently in hospitalist meetings than length of stay (LOS). The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted profit margins across the country and increased LOS. To combat this, health care systems must improve their overall LOS in a manner that is both effective and safe for patient care. Drs. McGillen and Ansari dove headfirst into this topic at SHM Converge in Austin, Texas. They focused more on the optimization of LOS management and not overtly on reducing or fixing LOS. In addition, they also spoke about how hospitalists are optimally positioned to tackle roles in health system leadership, as well as how to transition from bedside hospitalists to leadership roles at the unit and institutional levels.

They opened their presentation with the health care value equation: value equals quality plus service (measured by metrics such as outcomes and patient experience) divided by cost (both direct and indirect) and then multiplied by appropriateness (right place, right time, right patient, and right context).

Dr. Ansari used an excellent analogy of Ethan Hunt from the Mission Impossible movie series. Just as Ethan Hunt was asked to perform a mission that seemed impossible, hospitalists are asked daily to take on various inefficiencies in health care and be more efficient with them. And just like Ethan Hunt didn’t shy away from his challenge, neither should we!

Dr. Ansari used an excellent analogy of Ethan Hunt from the Mission Impossible movie series. Just as Ethan Hunt was asked to perform a mission that seemed impossible, hospitalists are asked daily to take on various inefficiencies in health care and be more efficient with them. And just like Ethan Hunt didn’t shy away from his challenge, neither should we!

The objectives of this talk were to: identify drivers that contribute to LOS management; describe effective methods to improve interdisciplinary rounds; recognize the unit medical director’s role in effecting change and streamlining care delivery processes; and illustrate the skillset necessary for leaders to best impact LOS optimization.

Drs. McGillen and Ansari shared the “ABCs of LOS Lingo”:

- Average length of stay (ALOS) is exactly what it sounds like, the average LOS for a group of patients for a specific diagnosis-related group (DRG).

- G(M)LOS is the geometric mean LOS, the “expected” LOS of a specific DRG. It is calculated using a square root function which removes potential outliers.

- Case mix index (CMI)-adjusted LOS is LOS/CMI. CMI is essentially an average of a hospital’s DRG relative values over time.

- O/E LOS, meaning observed divided by expected, is ALOS/G(M)LOS. G(M)LOS variance is the number of days exceeding a given G(M)LOS, which can also be called excess days.

- Understanding these phrases and abbreviations will help you effectively converse with hospital and system leadership.

There are various drivers of LOS occurring at different health care levels. At the bedside or unit level, geographic rounding, multidisciplinary rounds (MDR) and/or bedside rounding, early palliative care intervention, and prioritizing testing and/or procedures related to the principal diagnosis were all highlighted. At the hospital level, having a robust Utilization Management/Clinical Documentation Improvement (UM/CDI) department was discussed. The speakers emphasized the importance of a physician advisor program that can translate system goals to frontline workers, provide coaching and education on documentation needs and patient status, and have peer-to-peer conversations allowing the participation of bedside clinicians. At the system level, physician leaders need to set the tone regarding metrics, their urgency, and their application to clinical function. They also need to make sure data are being provided to frontline staff with appropriate interpretation and discussion. A key audience takeaway from this portion of the talk was the acknowledgment that the hospital medicine skillset beyond clinical knowledge applies to leadership at each of these levels.

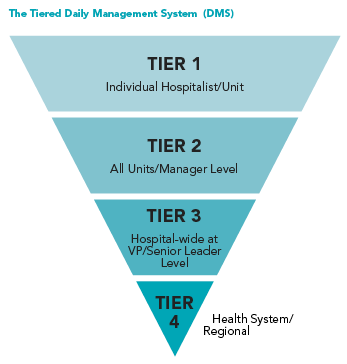

The presenters discussed the Tiered Daily Management System (DMS), as detailed in the following pyramid diagram. Tier 1 should focus on MDR, communication between the bedside nurse and physician, and establishing and updating an estimated date of discharge, identifying any barriers, and creating unit-level data. Drs. McGillen and Ansari then performed a demonstration of what a good MDR looks like compared to a bad one. I was especially impressed with how they incorporated denial-prevention and clinical-documentation-improvement queries into their MDR. Tier 2 should deal with escalating any obstacles identified in Tier 1, identifying testing delays, discussing bed shortages, and discussing unit-level metrics. Tier 3 should deal with escalating obstacles identified in Tier 2, discussing system outages or anything that can affect throughput, and hospital-wide metrics. Tier 4 should focus on broader, regional issues that affect throughput, regional bed control, and system-wide metrics.

The talk shifted to hospitalist leadership potential and how to transition from one level to the next on the corporate ladder.

To quote from their presentation: “There are 20,000 ‘medical directors’ out there without a skillset. How can you stand out?”

Drs. McGillen and Ansari grouped hospitalist physician leaders into four different categories: hospitalists, medical directors/physician advisors, those at the C-suite or institutional level, and those at the regional level such as chief medical officers or chief compliance officers. They emphasized the importance of understanding and defining “standard work” for each level.

For hospitalists, they mentioned UM/CDI learning, understanding social determinants of health, the importance of attending MDRs, and whether reverse rounding (i.e., rounding on discharges first) was beneficial.

For medical directors or physician advisors, they emphasized understanding payor sources, z-codes for social determinants of health, becoming versed in conflict resolution, and effective communication with senior leadership.

For those in the C-suite, they discussed understanding the DMS tiers, complex care principles, mentorship, narrative control (“staying ahead of the message”), performing Gemba walks (short for “Gembutsu”, which is Japanese for “the real place”; this is a Lean principle where leaders spend time in the place where the work actually occurs), and understanding “A3” methodology (this is a Lean problem-solving method and refers to the size of paper it is printed on). They also discussed “no meeting zones,” where no meetings are allowed for a certain number of hours in the early morning to improve productivity and allow the DMS system to work.

Key Takeaways

- Hospitalists are integral to LOS management but may not always recognize or embrace this fact. Skillful participation in every tier of multidisciplinary rounds is key to enhancing patient throughput, minimizing cost, and maximizing quality and revenue.

- Hospitalists are well-positioned to grow into medical director and/or physician advisor roles and can be impactful by effecting change and streamlining larger-scale delivery processes.

Dr. Craven

Dr. Craven is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and vice president of case management for McLeod Health in Florence, S.C. He is also on the executive council for the SHM Physician Advisor Special Interest Group.