By now, burnout and its related toll on clinicians nationwide are recognized as a pressing crisis. While burnout among U.S. health care practitioners isn’t new, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing issues and added novel stressors. A recent study showed that burnout, work overload, and COVID-19–associated stressors resulted in one in five physicians and two in five nurses intending to leave their current practice within the next two years.1 In addition to the ample negative impacts on individuals, burnout is a monumental staffing challenge hospital medicine groups must face.

Read Pierce, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas, shared how the pandemic led him to a first in his career: having to sit down with some of his staff and tell them they needed to see a mental health professional. “There’s such a stigma around that and we’ve been trained to set it aside or avoid it. Those were real challenges, and I knew we needed to do more than the usual things to keep people supported,” he said.

Read Pierce, MD, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas, shared how the pandemic led him to a first in his career: having to sit down with some of his staff and tell them they needed to see a mental health professional. “There’s such a stigma around that and we’ve been trained to set it aside or avoid it. Those were real challenges, and I knew we needed to do more than the usual things to keep people supported,” he said.

As 2022 began and the Omicron variant was in full force, Dr. Pierce saw burnout rates nearly double from the prior year to 50% within his group. As burnout rates increased, the rate of volunteerism among his group drastically decreased, something Dr. Pierce had never seen among his team. He saw the lack of volunteerism as a sign of self-preservation for his group members.

Due to its association with loss of empathy, impaired job performance, and increased incidence of medical errors, burnout has a major impact on patients as well as the health care system as a whole.2 Dr. Pierce reflected on how he saw in his group and hospital that burnout was linked to effects on patient care. “The patient experience care scores went down, length of stay increased, and patient safety events like infection rose. A lot of measures got worse,” said Dr. Pierce.

One study found that physicians experiencing burnout are more likely to be involved in patient safety incidents, fail on critical aspects of professionalism that determine the quality of patient care, and receive lower patient-experience ratings.3 Physician burnout, along with its downstream effects, is estimated to cost the health care system approximately $4.6 billion a year.4

Dr. Pierce, along with 11 hospitalist leaders, joined SHM’s Well-being Task Force, which was created early in 2020 to address the new circumstances hospitalists were facing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Task force members shared their personal experiences and the different tools and interventions they implemented within their groups to ease burnout and promote well-being among physicians, and they quickly realized the potential value of a resource designed to empower individuals at any level to promote and advance well-being at their institutions. The group used an iterative process to assemble and categorize tools and tips that they and their peers used in their hospital medicine groups.

Out of these conversations came the Well-Being Advocates Toolkit, which has practical tools for hospitalists to make real changes, however small, in their groups. The resource is organized for hospitalists at any level—whether you have a formal well-being role, a hospitalist leader role, or simply feel compelled as a frontline hospitalist to improve the well-being of your team.

One intervention Dr. Pierce began to implement within his group, which can be found in the toolkit, was formally scheduled check-ins using a check-in guide. “Very early on we started using it and doing check-ins. It was important to pause and see how we’re doing as human beings before we started the work. I’d always done one-on-one check-ins when I ran into people within my group, but I started two years ago to schedule them to make sure I was supporting them more consistently. They were powerful even if sometimes they were hard. People appreciated that it was a formal focus in the group.”

Dr. Pierce has also seen a positive change in his group since he began implementing tools and interventions from the toolkit. “Volunteerism is way back up and we have seen the palpable levels of group anxiety is lower. We’ll measure burnout this spring and we expect it to be lower than when we measured it last. When I looked at the rate of turnover compared to those around town, we’ve done a lot better. I think a lot of these tools really attended to the workforce and its well-being,” said Dr. Pierce.

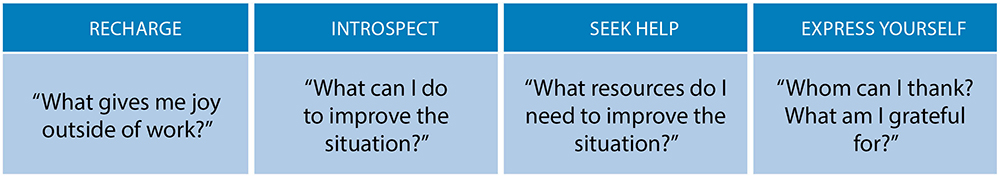

When hospitalists begin to use this toolkit, the first step is to do a quick self-check-in to gauge their own well-being using the R.I.S.E. for self-care (recharge, introspect, seek help, express yourself) mnemonic.

Next, hospitalists should identify which of the three well-being advocate personas best applies to them: The hospitalist—I care, but don’t have a formal leadership role; the hospitalist leader—I want to use my position of leadership to make a difference, and the well-being leader—I’m a well-being expert and I need more than just the basics. Within each persona description are activities for hospitalists to adopt and implement in their group or institution.

Hospitalists can start small, even if implementing just one activity and/or change might seem insignificant. Little interventions can have a large ripple effect that far outweighs their effort or cost. The SHM Well-being Task Force believes the strategies and tips in the toolkit can help improve well-being, create supportive hospital medicine workplaces, and contribute to decreasing burnout in hospital medicine.

To access more resources on well-being and burnout prevention, SHM members can visit the Well-Being page of SHM’s website and subscribe to the recently established Hospitalist Well-being Special Interest Group (SIG). The SIG was approved by the Board of Directors in February 2023, and it intends to provide an enduring virtual space on the Society’s online networking platform Hospital Medicine eXchange (HMX) that connects SHM members who are interested in learning more or engaging around this important topic.

Toolkit Testimonials

Hospitalist Megha Shah, MD, MMM, FHM, from Saint Joseph Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash., saw an improvement among her team after instituting strategies from SHM’s Hospitalist Well-being Advocates Toolkit. Some of the strategies they used included beginning meetings with kudos, having formal acknowledgments in meetings, flexibility for meetings to be in person or virtual, and sending personalized messages of gratitude to team members. She said, “I was seeing my team struggle during the pandemic and its aftermath of rising census and short staffing. [The changes we implemented] have improved my team’s morale and engagement.”

Anum A. Niazi, MD, a hospitalist and hospital medicine lead advocacy coordinator for Vituity in Munster, Ind., said “This toolkit is an incredible resource. It allows us to reflect on areas of our own improvement and empowers us to help others use the great R.I.S.E. checklist. The ideas this toolkit can spark can lead to meaningful improvements as it even touches on the importance of DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] and tactics to normalize being human.”

Dr. Mehta

Ms. Zachwieja

Dr. Mehta is the national director of quality and patient experience for Vituity, a physician-led health care innovation company based in Emeryville, Calif., and a practicing hospitalist at CommonSpirit Sequoia Hospital in Redwood City, Calif. She’s the chair of SHM’s patient experience executive council and a faculty member of SHM’s well-being task force. Ms. Zachwieja is a practice management specialist at SHM.

References

- Sinsky CA, et al. COVID-Related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(6):1165-73.

- Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2485-7.

- Panagioti M, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-31. Retraction in: JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):931. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):596.

- Han S, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-90.