Case

A 93-year-old female with dementia and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) presented after a mechanical fall. She was on apixaban for a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) from three months prior, which was complicated by an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Evaluation in the emergency department revealed a left femoral neck fracture. She was admitted to the care of the orthopedic trauma team and the geriatric medicine team was consulted for medical co-management.

Brief overview of the issue

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, where extracellular amyloid beta plaques deposit in the tissues between nerve cells, CAA is defined by amyloid beta plaques collected within the media and adventitia of small- and medium-sized blood vessels of the brain.1

Hereditary CAA is rare and occurs most commonly in the younger population whereas sporadic CAA has greater prevalence and severity with increasing age.2 While a definite diagnosis of CAA can only be established postmortem via a pathologic exam showing amyloid deposition, a probable diagnosis is often made in living patients and may be supported by MRI imaging.

Characteristic findings can include multiple acute hemorrhagic cerebral lesions or chronic changes including microbleeds with hemosiderin deposition, white matter changes, and “microinfarctions.” 3 With CAA comes a greatly increased risk of ICH which can be problematic for patients at risk of falls or those indicated for anticoagulation therapies.

Overview of the data

CAA carries a high risk of spontaneous intraparenchymal bleeding and its prevalence increases with age in the elderly population.2 The proportion of spontaneous hemorrhages attributed to CAA in elderly patients ranges from 10% to 20% in the autopsy series and up to 34% in the clinical series.4,5 In individuals affected by CAA, prior ICH has been associated with a 10-fold increased risk of recurrent ICH compared to those without.6

Warfarin has been found to increase the risk of ICH by seven to 10 times.7,8 Furthermore, it increases the severity of bleeding, accounting for approximately 60% of associated mortality.9 Aspirin has also been shown to increase the risk of intracerebral bleeding.10 No study has reported the effect of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) on CAA specifically.

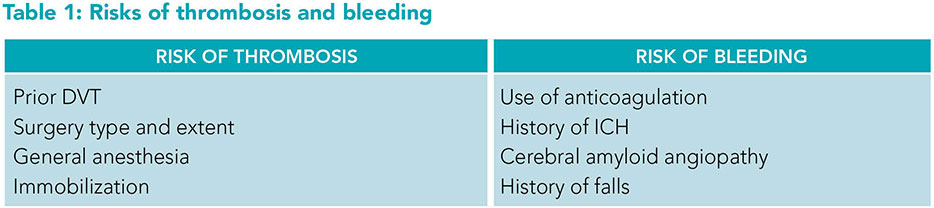

While our patient had an increased bleeding risk from CAA, this was complicated by her acute long bone fracture with conflicting risks of its own. There is a high risk of DVT associated with long bone fractures,11 as well as with surgical procedures and general anesthesia.12,13 Poor mobility after falls, especially in the setting of fracture, adds to the risk of developing DVT.14 Another notable risk in this patient is her advanced age and history of frequent falls. Orthopedic hip surgery has a known increased risk of VTE events which can be reduced by up to 60% with thromboprophylaxis.15 The American College of Chest Physicians recommends routine use of DVT prophylaxis for at least 10 to 14 days minimum and extending up to 35 days.15

While our patient had an increased bleeding risk from CAA, this was complicated by her acute long bone fracture with conflicting risks of its own. There is a high risk of DVT associated with long bone fractures,11 as well as with surgical procedures and general anesthesia.12,13 Poor mobility after falls, especially in the setting of fracture, adds to the risk of developing DVT.14 Another notable risk in this patient is her advanced age and history of frequent falls. Orthopedic hip surgery has a known increased risk of VTE events which can be reduced by up to 60% with thromboprophylaxis.15 The American College of Chest Physicians recommends routine use of DVT prophylaxis for at least 10 to 14 days minimum and extending up to 35 days.15

See Table 1 for a comparison of factors increasing bleeding risk versus thrombosis risk.

Application to case

We evaluated this patient for preoperative risk prior to anticipated orthopedic surgery. Given that she was ambulatory at baseline and had no identified risk factors on the Revised Cardiac Risk Index she did not require further preoperative diagnostic assessment.16 Apixaban was held upon admission, and on hospital day number one, she successfully underwent closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of the femoral neck.

Following surgery, a discussion of the risks and benefits regarding anticoagulation occurred in a patient-centered manner with an interdisciplinary team that included the patient, family, the orthopedic team, and geriatric medicine team. An ultrasound of the lower extremities was repeated during this hospitalization to evaluate for any residual clot burden, which was negative. The ultrasound result, in addition to her CAA history and orthopedic surgery, were all significant factors in this discussion.

A patient-centered plan was made with a decision to stop anticoagulation altogether and indefinitely. As recommended by physical therapy, she was encouraged to ambulate daily with assistance and to use anti-embolism stockings and sequential compression devices for non-pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis.

Bottom line

CAA dramatically increases the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and requires extreme caution when considering anticoagulation therapies.

Key Points

- CAA dramatically increases the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and requires extreme caution when considering anticoagulation therapies.

- A patient-centered and multidisciplinary approach to management is required when considering the competing risks of bleeding versus thrombosis in patients with CAA.

- Characteristic MRI findings of CAA can include multiple acute hemorrhagic cerebral lesions or chronic changes including microbleeds with hemosiderin deposition, white matter changes, and “microinfarctions.”

Additional Reading

- Corovic A, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy associated with inflammation: A systematic review of clinical and imaging features and outcome. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(3):257-267.

- Graff-Radford J, Rabinstein AA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy criteria: the next generation. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(8):674-6.

- Samarasekera N, et al. The association between cerebral amyloid angiopathy and intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(3):275-81.

Quiz:

Identifying CAA

1. You receive the pathology report after an examination of the brain of an 89-year-old patient who passed away from ICH secondary to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Which of the following characteristic findings would you expect the pathologist to have found in your patient with cerebral amyloid angiopathy?

A. Amyloid beta plaque deposition in tissues between nerve cells

B. Tau fibrillary tangles on brain imaging

C. Amyloid beta plaque deposition within blood vessels of the brain

D. Multifocal white matter lesions representing demyelinating plaques

Answer: C. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is notable for amyloid-beta plaque deposition within the media and adventitia of the small and medium-sized blood vessels of the brain. This is distinguishable from Alzheimer’s disease, where hallmarks include the presence of extracellular amyloid beta plaques deposited in the tissues between nerve cells and tau fibrillary tangles. The last answer choice is often found in multiple sclerosis patients upon neuroimaging such as FLAIR MRI.

Effect of cerebral amyloid angiography on bleeding risk

2. One of your patients has CAA. They don’t know much about CAA and are wondering what some of the major risks of this disease are. You tell them:

A. CAA has an increased risk of ICH

B. CAA has an increased risk of pulmonary fibrosis

C. CAA carries no increased risk; reassure the patient their condition will not affect their health

D. CAA has an increased risk of peripheral neuropathy

Answer: A. In individuals affected by CAA, prior ICH has been associated with a 10-fold increased risk of recurrent ICH compared to those without. There is a high stroke risk for those with CAA and it should be one of the major concerns when treating a patient with CAA. The rest of the answer choices are incorrect–there are no known associations of CAA with lung hypoplasia or peripheral neuropathy.

Managing CAA with comorbidities

3. A 73-year-old patient is recovering from a spontaneous lobar hemorrhage and was subsequently found to have CAA by MRI. Her past medical history includes atrial fibrillation which is currently being managed with warfarin. You discuss with the patient that:

A. She should maintain her current warfarin therapy

B. She should be switched from warfarin to a DOAC for easier management

C. She may be a candidate for a left atrial appendage closure procedure and taken off anticoagulant therapy

D. Both B and C are suitable options after having a patient-centered discussion of the risks and benefits of both options

Answer: D. Warfarin confers the highest risk of ICH in CAA patients making DOACs the more preferable choice for anticoagulation. In addition, given this patient’s history of spontaneous bleeding, the provider may deem her unsuitable for any future anticoagulant treatment and recommend a left atrial appendage closure to prevent the risk of clotting due to her atrial fibrillation. In all cases of CAA, a patient-centered discussion should be held to identify the most appropriate course of treatment.

Best approach to DVT prophylaxis

4. An 87-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department by her son after falling at home and reportedly not being able to ambulate. There is no history of head trauma. Her past medical history includes ICH secondary to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Physical examination shows moderate tenderness to the left hip and a limited range of motion. X-ray reveals an intertrochanteric hip fracture. The patient decides to undergo open reduction internal fixation of the hip. What is the best approach to DVT prophylaxis for this patient?

A. Start the patient on low molecular weight heparin prior to surgery and continue its use up to 35 days post-surgery

B. Discuss with the patient and her health care team the risks and benefits of starting anticoagulation prophylaxis prior to commencing surgery

C. Continue with surgery without initiating prophylactic medication

D. Start the patient on rivaroxaban prior to surgery and discontinue immediately post-surgery

Answer: B. While the American College of Chest Physicians recommends the use of DVT prophylaxis for at least 10 to 14 days minimum and up to 35 days post-surgery, the patient has a history of CAA which confers a risk of suffering another ICH. The best approach would be to discuss with both the patient and her health care team the risks and benefits of DVT prophylaxis in order to come up with a shared final decision.

Dr. Nepaul

Ms. Guo

Ms. Fierro

Mr. McCrae

Dr. Mujahid

Dr. Neupane

Dr. Nepaul is a geriatric medicine fellow at the Warren Alpert Medical School, division of geriatric and palliative medicine, at Brown University in Providence, R.I. Janet Guo, BS, Cassandra Fierro, BS, and Brian McCrae, BS are medical students at the Warren Alpert Medicine School of Brown University in Providence, R.I. Dr. Mujahid is co-director of the geriatric fracture program at Rhode Island Hospital, medical director for the transitional care unit at Steere House Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, and associate professor of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, R.I. Dr. Neupane is a geriatrician at Rhode Island Hospital and Miriam Hospital, an assistant professor in the division of geriatrics and palliative medicine, and the geriatric medicine fellowship associate program director at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, R.I.

References

- Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(6):871-80.

- Biffi A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol. 2011;7(1):1-9.

- Charidimou A, et al. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(2):124-37.

- Jellinger KA. Alzheimer disease and cerebrovascular pathology: an update. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2002;109(5-6):813-36.

- Greenberg SM. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. New York: Harcourt Inc;2004;693–697.

- Biffi A, et al. Aspirin and recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2010;75(8):693-8.

- Franke CL, et al. Intracerebral hematomas during anticoagulant treatment. Stroke. 1990;21(5):726-30.

- Rosand J, et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004;26;164(8):880-4.

- Rosand J, et al. Warfarin-associated hemorrhage and cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a genetic and pathologic study. Neurology. 2000;55(7):947-51.

- Huang W, et al. Frequency of intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose aspirin in individuals without symptomatic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(8):906-914.

- Mioc M, et al. Deep vein thrombosis following the treatment of lower limb pathologic bone fractures – a comparative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):213.

- Heit JA, et al. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(1):452-63.

- Gordon RJ, Lombard FW. Perioperative venous thromboembolism: a review. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(2):403-12.

- Weill-Engerer S, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in inpatients aged 65 and older: a case-control multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1299-304.

- Falck-Ytter Y, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S-e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404.

- Fleisher LA, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(24):2215-45.