Case

A 50-year-old male with a medical history of severe alcohol use disorder and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and dry cough. Initial venous blood gases showed a pH of 7.06, anion gap of 41, and lactate of 5.19 mmol/L. After fluid resuscitation, glycemic control, and standard thiamine replacement, the patient’s lactate remained elevated.

Overview

Elevated lactate is a common finding in hospitalized patients.1

Elevated lactate is a common finding in hospitalized patients.1

Hyperlactatemia is defined as a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L. Lactic acidosis is elevated lactate in the setting of pH under 7.35.2 The differential diagnosis for elevated lactate is exceedingly broad and thus finding a definitive diagnosis can be difficult, especially in patients with complex medical histories. Generally, high lactate levels can be grouped into two categories: hypoxia, and underlying disease (which can include sepsis, malignancy, thiamine deficiency, liver failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and alcoholic ketoacidosis). Toxicities from a variety of substances and inborn errors of metabolism should also be considered.1 In this case, the patient presented with lactic acidosis secondary to a variety of potential causes.

While the underlying cause of lactic acidosis affects the prognosis greatly, elevated lactate levels are associated with a poor prognosis. In one study, an initial lactate of 4 mmol/L or higher was associated with a 28% in-hospital mortality rate.3 There is no specific timeframe or percentage decrease for normalizing lactate, but decreasing lactate concentrations are associated with improved mortality.2 The definitive treatment for lactic acidosis is resolving the underlying cause. Volume resuscitation and adequate oxygenation are also important.1

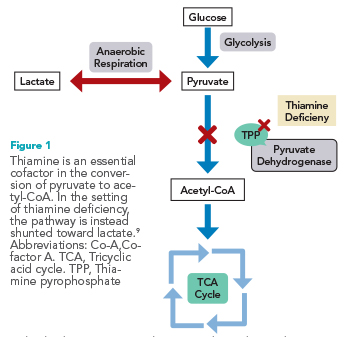

One cause of elevated lactate is thiamine deficiency. Thiamine is an essential cofactor in the tricyclic acid (TCA) cycle, aiding in the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl CoA as thiamine pyrophosphate.4 In the setting of thiamine deficiency, cells are unable to enter the TCA cycle and thus are shunted toward anaerobic metabolism, which produces excess lactate.2 In the U.S., thiamine deficiency is primarily caused by chronic alcohol use or chronic illness. There are several mechanisms by which chronic alcohol use leads to thiamine deficiency, including inadequate nutritional uptake and impaired absorption of thiamine within the small intestine.5,6 Unfortunately, there is no definitive diagnosis of thiamine deficiency and laboratory testing of thiamine levels is not widely available.7 Treatment of thiamine deficiency involves supplementation. Typically, 100 mg is considered a standard treatment dose, however, in the setting of persistent hyperlactatemia, high-dose thiamine (250 to 500 mg) may be appropriate.8

Back to the case

In the setting of multifactorial acidosis, it can be difficult to differentiate the main drivers of elevated lactate. In this case, the patient’s fluid resuscitation, glycemic correction, and bicarbonate administration were not sufficient to lower the patient’s lactate level. The patient’s alcohol abuse disorder led him to be chronically thiamine deficient. His thiamine deficiency hindered metabolism through the TCA cycle (See Figure) leading to regular production of lactate, perpetuating hyperlactatemia and an acidotic state. While the patient was treated with a standard dose of thiamine 100 mg on admission, this proved insufficient to fulfill this patient’s metabolic needs. High-dose thiamine, while not indicated in every patient with chronic alcohol use, should be considered as a treatment for persistent hyperlactatemia.8 After a 500-mg dose of thiamine, the patient’s lactate began to trend downward, with the hyperlactatemia eventually resolving.

Bottom line

Thiamine deficiency can cause production of lactate by shunting glycolysis away from aerobic metabolism. In some situations, high-dose thiamine replacement is necessary to normalize lactate levels.

Key Points

- Elevated lactate is associated with a higher mortality rate in hospitalized patients. Potential underlying causes of hyperlactatemia are numerous and can be difficult to determine in complex

medical cases. - Thiamine is necessary for aerobic metabolism of cells. In the setting of thiamine deficiency, cells undergo anaerobic metabolism which produces excess lactate.

- In the setting of a severe alcohol use disorder, high-dose thiamine (500 mg daily) can help normalize lactate levels if standard thiamine dosing is not sufficient.

Quiz

A 76-year-old female with alcohol use disorder is admitted to the hospital for urosepsis with symptoms of confusion. Labs demonstrate positive urine cultures, lactate of 4.1 mmol/L, and venous blood gases showing pH of 7.35, PaCO2 of 39 mm Hg, and HCO- of 24 mEq/L. In

addition to appropriate antibiotics and alcohol withdrawal protocol, what additional therapies should be started?

a. Haloperidol

b. 100 mg thiamine orally daily

c. 500 mg thiamine, high-dose protocol three times daily

d. Sodium bicarbonate

Correct option: B. While high-dose thiamine may be indicated for persistently elevated lactate levels, a standard dose of thiamine (100 mg daily) is recommended for a starting dose. Haloperidol and other antipsychotics may be indicated in the setting of agitation and aggression

but are not used as first-line therapy for confusion or delirium. Sodium bicarbonate may be indicated in the setting of severe acidosis but is not necessary in this case, as the pH is within normal limits.

Dr. Skarda

Ms. Meirhoff

Dr. Skarda is a hospitalist and primary internist at HealthPartners and Regions Hospital in Saint Paul, Minn. She is also an associate program director for the University of Minnesota Internal Residency Program and chair of credentialing at Regions Hospital.

Lillian Meierhoff is a 4th-year medical student at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. She is hoping to match into emergency medicine this spring

References

- Masharani U. Lactic acidosis. In: Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, McQuaid KR, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2023. McGraw Hill; 2023. Available at: https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3212§ionid=269151066. Accessed January 6, 2023.

- Wardi G, et al. Demystifying lactate in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(2):287-98.

- Shapiro NI, et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(5):524-8.

- Bubber P, et al. Tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes following thiamine deficiency. Neurochem Int. 2004;45(7):1021-8.

- Sanvisens A, et al. Folate deficiency in patients seeking treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:417-22.

- Hoyumpa AM. Mechanisms of thiamin deficiency in chronic alcoholism. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33(12):2750-61.

- Lykstad J, Sharma S. Biochemistry, water soluble vitamins. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Published January, 2022. Updated March 9, 2022. Accessed January 6, 2023.

- So YT. Wernicke encephalopathy. Up To Date. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/wernicke-encephalopathy. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2023.

- Thota V, et al. Treatment of refractory lactic acidosis with thiamine administration in a non-alcoholic patient. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16267. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16267.