Case: A 26-year-old woman with a history of poorly controlled Crohn’s Disease (CD) presents to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of progressively worsening diarrhea for the past two weeks, having 11 to 14 episodes of bloody stools per day. Due to fears that eating would make her diarrhea worse, she reports little oral intake over the last six days. On admission, her body mass index (BMI) is 17.

Brief overview of the issue

Dr. Feagins

Dr. Vasudevan

Patients with severely active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are commonly admitted to the hospital for disease management. Common symptoms of CD and ulcerative colitis (UC) include diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, which can lead to reduced appetite, difficulty eating, and increased risk for malnutrition. Malnutrition is seen with a greater frequency in CD than in UC, presumably due to CD’s involvement of the small bowel. Estimates of malnutrition vary based on study design, reporting prevalence rates ranging between 10 and 35% in IBD patients.1 Further, a study using national administrative data to evaluate the prevalence of protein energy malnutrition (PEM) found that patients with IBD were more likely to have PEM compared to patients admitted with other diagnoses.2

The mechanisms underlying the development of malnutrition in IBD are multifactorial and include symptoms limiting oral intake (i.e., nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea), enteral loss of protein and electrolytes, interference of absorption of nutrients by certain drugs, sequelae of gut resections, increased metabolic demands from active inflammation, and self-imposed diet restrictions by patients.3

Importantly, malnutrition in the IBD population affects overall patient morbidity as well as inpatient outcomes. Underlying malnutrition in hospitalized IBD patients is associated with increased lengths of stay, increased need for non-elective surgery, increased risk for venous thromboembolism, higher readmission rates post-discharge, and increased mortality.4 Thus, hospitalizations for active IBD flares may serve as valuable opportunities to mitigate these complications through early identification and treatment of nutritional deficiencies, especially as laboratory investigation and nutritional team support are readily available in the inpatient setting.5

Overview of data

Screen for malnutrition

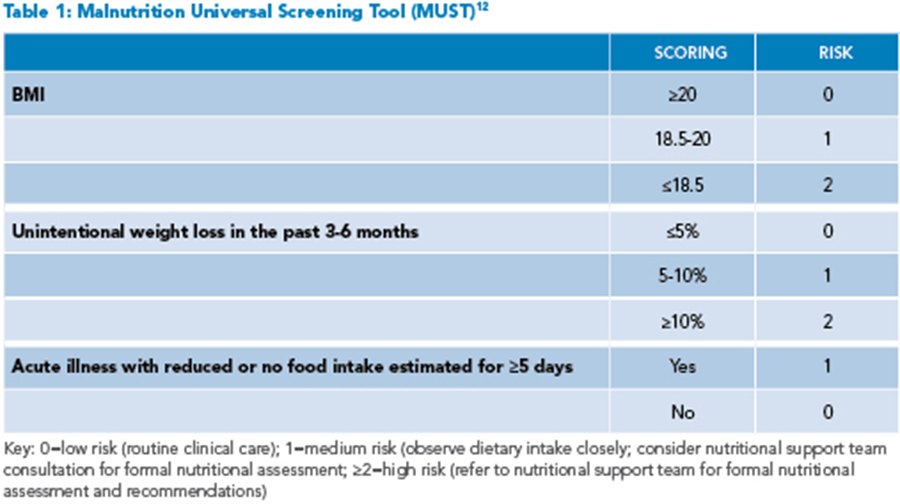

Given the significant risk of nutritional compromise, all patients hospitalized for acute IBD flares should be screened for malnutrition on admission. Several screening tools, including the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) or Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), are short questionnaires easily used in the inpatient setting that assess three to four risk factors to stratify the patient’s risk for malnutrition (See Table 1).6 These screening tools are readily available online and can be completed by the hospitalist or care team. All patients, regardless of BMI, should undergo screening, as patients without low BMIs may also be malnourished.5 For patients identified as medium or high risk for malnutrition, inpatient dietitian support team consultation should be sought for formal nutritional assessment and recommendations.

Albumin is not a reliable marker of nutritional status

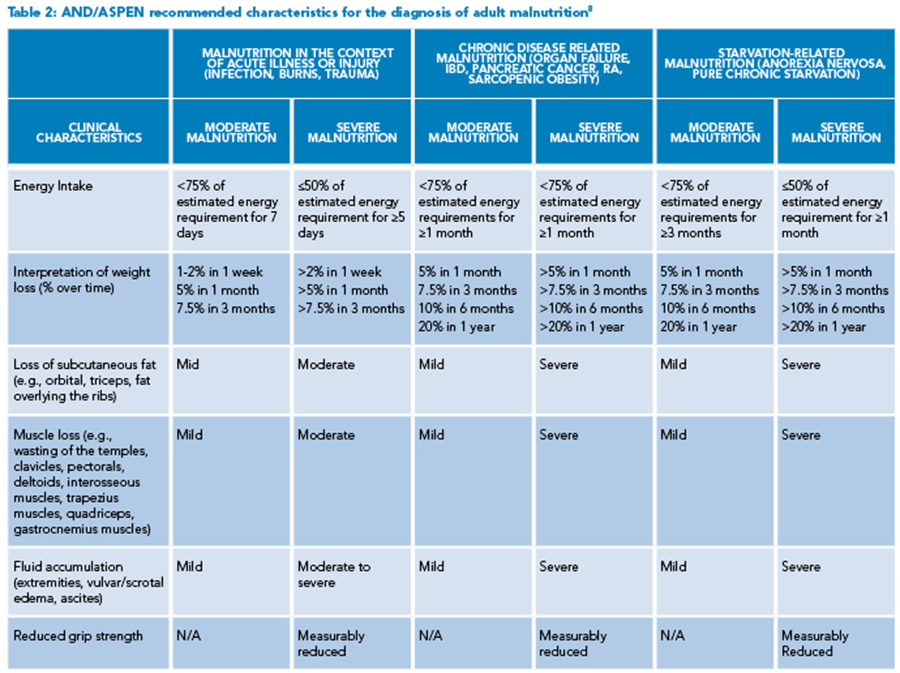

Of note, when identifying patients at risk of malnutrition, albumin and prealbumin are often used as markers for nutritional status; however, both markers are decreased in acute inflammatory states and thus can be misleading.7 More reliable markers include insufficient energy intake, weight loss, loss of subcutaneous fat, muscle loss, fluid accumulation, and reduced functional status as measured by grip strength (See Table 2).8

Most IBD patients should be given a diet

During hospitalization, malnutrition states can be worsened with iatrogenic nil per os (NPO) orders that may further impact undernourished patients. In a retrospective cohort study of 187 patients admitted for acute UC flares, 252 NPO or clear fluid dietary orders were encountered among 142 admissions (75.9%). Among these orders, 112 orders (44%) were not justified or did not offer alternative nutrition sources, such as enteral nutrition (EN) or parenteral nutrition (PN).9 Current guidelines recommend initiating a regular diet as the patient can tolerate, if no contraindications are present, with oral routes of feeding being preferred over EN. Contraindications to initiating a diet include uncontrolled sepsis, patients requiring urgent or emergent surgery (such as small bowel obstruction or abscesses), patients with obstructive symptoms, or fistulas with high output (>500 cc/day). Although there are no current recommendations for use of a specific IBD diet during active flares, the European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recommends increasing protein intake to 1.2 to 1.5 mg/kg/day in adults in patients with active disease, and oral nutritional supplements may be considered for this purpose.4 For patients with symptomatic strictures, low fiber diets or post-stenosis EN can be considered, though evidence to support these diets is weak.

Consider other causes for difficulty eating

If the patient is unable to tolerate a diet despite pharmacologic treatment for an acute IBD flare, the clinician should consider possible contributory organic causes that may be limiting oral intake, which may warrant further evaluation and treatment.10 For example, patients with CD with continued nausea and vomiting despite steroids and antiemetic therapy may require esophagogastroduodenoscopy or abdominal imaging, if not already performed, to evaluate for upper gastrointestinal tract involvement, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or presence of strictures, as well as a careful review of current medications that could be contributing to their symptoms.

Application of data to our case

Using the MUST screening tool, the patient is deemed high risk for malnutrition, and the inpatient dietitian is consulted. On nutritional assessment, she is found to have moderate protein-energy malnutrition based on findings of 5% body weight loss in the last month, evidence of muscle loss, and ongoing symptoms of frequent diarrhea. She is initiated on a regular diet with high calorie/high protein supplements with every meal and close monitoring of her oral intake. Antiemetics are given before meals to reduce nausea and increase the ability to eat. Her diarrhea slowly improves with intravenous corticosteroid treatment and plans are made for starting a new biologic as an outpatient. It was noted that the patient was anemic with Hb <10 g/dL and low iron saturation and ferritin. Intravenous iron supplementation was initiated due to concerns for intolerance to oral iron supplements (as well as concerns of malabsorption with active disease.) She was recommended to follow up with a registered dietitian as a part of her discharge planning to ensure ongoing nutritional support during her treatment.

Bottom line

Data supports screening for malnutrition in all patients hospitalized with IBD and that bowel rest should be avoided in most patients.

Dr. Vasudevan is a hospitalist for the division of hospital medicine and a research associate for the division of gastroenterology and hepatology for the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas. Dr. Feagins is an associate professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School, a board-certified gastroenterologist, and director of the Center of Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Digestive Health, a clinical partnership between Dell Med and Ascension Seton in Austin, Texas.

References

- Liu J, et. al. Prevalence of malnutrition, its risk factors, and the use of nutrition support in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(Suppl 2):S59-S66.

- Nguyen GC, et al. Nationwide prevalence and prognostic significance of clinically diagnosable protein-calorie malnutrition in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(8):1105-11.

- Chiu E, et al. Optimizing inpatient nutrition care of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1581.

- Forbes A, et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(2):321-47.

- Palchaudhuri S, et al. Diet recommendations for hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel disease: better options than nil per os. Crohn’s Colitis 360. 2020;2(4):otaa059. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otaa059.

- Lin A, Micic D. Nutrition considerations in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36(2):298-311.

- Vasudevan J, et al. Optimizing nutrition to enhance the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2022;18(2):95-103.

- White JV, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730-8.

- Gallinger Z, et al. A315 Frequency and predictors of fasting orders in inpatients with ulcerative colitis: the audit of diet orders – ulcerative colitis (ADORE-UC) study. Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. 2018;1(Suppl 1):547-8.

- Hwang C, et al. Development and pilot testing of the inflammatory bowel disease nutrition care pathway. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(12):2645-9.

- Park YE, et al. Is fasting beneficial for hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases? Intest Res. 2020;18(1):85-95.

- Anthony PS. Nutrition screening tools for hospitalized patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(4):373-82.