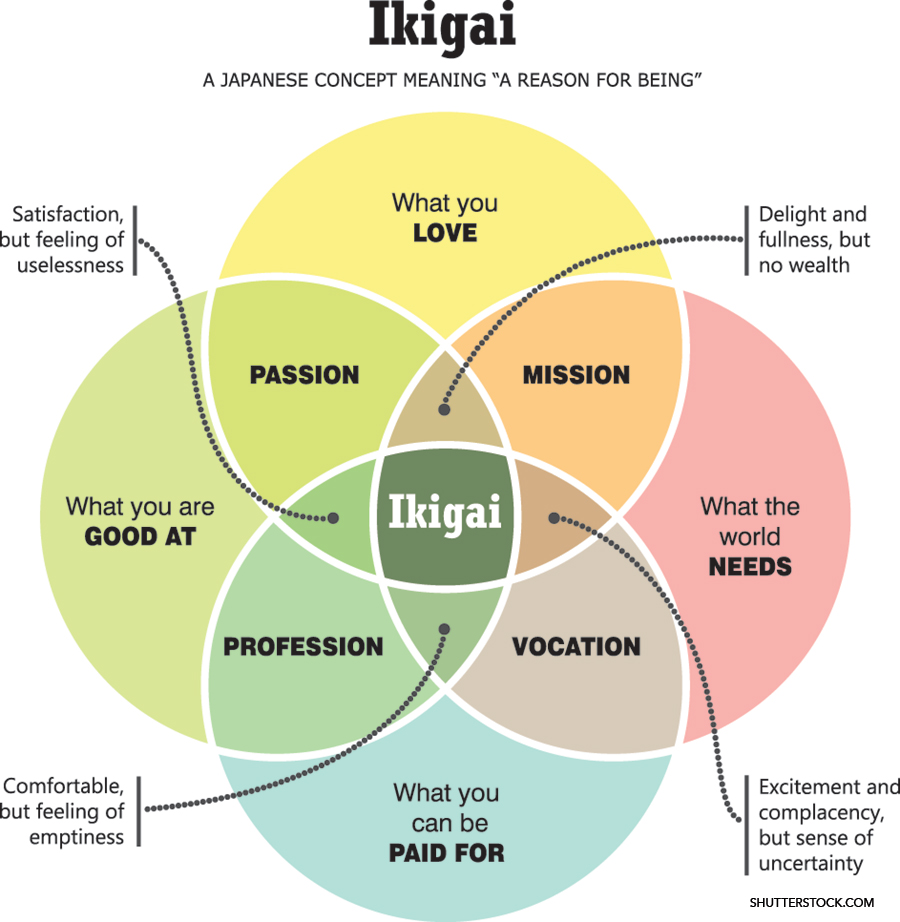

We enter the profession of medicine in the name of patient care. Our desire to better the health of our patients and communities is the tie that binds us together. But in today’s world of medicine, hospitalists are not limited to clinical care alone. We are at the forefront of scientific research, administration, policy, advocacy, quality and safety, medical education, informatics, technology, and more. As Dr. Mark Shapiro, a fellow hospitalist and host of Explore The Space podcast says, we are “pluripotent.” How, then, do we find that “something” in our careers that complements our clinical practice and aligns with our mission? What is our raison d’être and how do we find it? Enter ikigai—a Japanese concept meaning “reason for being.” By asking ourselves and reflecting on four key questions, we can use our answers to find the joy, meaning, purpose, and fulfillment we seek.

What do you love?

Dr. Patel

Dr. Patel

I often think about why I love medicine. For me, that answer is innovation and curiosity. Curiosity may have killed the cat, but it fuels and motivates me every day. I love asking questions, finding answers, and learning how to integrate those answers into solutions. I enjoy asking, “Why?” and seeing what I can do with the answer(s). What better place to be curious than in medical education? I get to learn every day from my patients, my colleagues, and my learners. I get to take that knowledge and reflect on it, disseminate it, and help learners, programs, and systems grow to become the best versions of themselves.

I have used that curiosity to explore curriculum development, global health opportunities, point-of-care ultrasound teaching, and clinical informatics. In all those opportunities, medical education has always been the common thread as a place to foster that inquisitiveness. For me, rather than focusing on a single tangible thing I love, I focus on the concept of curiosity as what I love. That guiding principle helps me decide what areas of interest I choose to explore when opportunities arise. If there is an opportunity for internal learning while allowing me to add external value, I am likely to incorporate it into my non-clinical “something.” As you navigate your journey as a hospitalist, ask yourself what you love to do and how that can be generalized to your non-clinical time.

What are you good at?

Dr. Sansbury

Dr. Sansbury

An important principle in the pursuit of career satisfaction is to identify and cultivate what you are good at. Author James Clear, the habit guru, wrote “What looks like talent is often careful preparation. What looks like skill is often persistent revision.” Many of us have found our careers in hospital medicine after careful identification of what we are good at early on in life—excelling in the classroom, identifying with and relating to others, recognizing problems, solving problems, and sharing stories with learners and patients. These skills, though, have taken years of deliberate practice to hone and perfect.

As an early-career hospitalist, relying on what I already knew I was good at was not enough to ensure I had fulfillment in my day-to-day work. This is where I found academic medicine and all the joys it has brought to my daily routine. I found a deep passion in teaching others, relating to learner-dependent issues, and developing this skill each day to become a better clinician and educator. This opened doors to teaching in our hospital’s simulation and ultrasound lab, which has afforded me additional administrative time and the excitement of learning new skills and sharing them with others.

Start with your skills and strengths. Develop those in a way that gives you joy. If you can identify what you are good at, generalize that to other arenas and practice deliberately—you can ultimately pursue your ikigai.

What does the world need?

Dr. Ganith

Dr. Ganith

As a physician, I always thought my role was to help my patients understand their disease, alleviate pain, end suffering, and extend life. Over the past 10 years, I acquired the sense that my obligation extends further.

One day, I entered the room of my patient with advanced cancer and immediately noticed telescopes of multiple sizes lined alongside his windowsill. My immediate duty was to alleviate his pain and discuss his prognosis. I simultaneously listened to stories about his telescopes. He spoke of each constellation and planet he had seen in his lifetime and how each telescope gave him a different view of our solar system. His words and thoughts spilled out continuously, and in that moment, I knew I had another purpose. We spoke of his prognosis, and I helped him navigate his next steps while engaging him in our conversations by intertwining his intergalactic interests. To him, watching the stars from his hospital room window brought him joy in a sea of sadness. I developed a deeper compassion for his will to live and remained a listening ear, as he had no one else to share with. We prayed together with the chaplain, listened to music with the music therapist, and looked at the planets when I was on call one night. He needed more than just a medical doctor; he needed a human connection.

After those seven days, I imagined another path, one separate from clinical medicine, by which I would continue to serve my patients. I would be a listener and an emotional support. Delivering bad news is never easy, but connecting with each patient’s passion reinvigorated my joy and wellness. I connect patients with resources; I listen when they advocate; I educate; I combat medical misinformation. I am dynamically supporting patients and ensuring they have a feeling of contentment when they are discharged from the hospital. In my pursuit of ikigai, I prioritize their wellness, so that I may prioritize my own.

What can you be compensated for?

Dr. Nelson

Dr. Nelson

Perhaps the most challenging part of ikigai is being compensated for your efforts. As a hospitalist, compensation can take many forms—salary, funding, protected time, and/or additional clinical and administrative resources.

Demonstrating the value and importance of your pursuits, your worth, may be challenging to define. Developing your mission and purpose early in your career and integrating them with your profession and vocation may allow visualization of future payoffs. Proactively seek and apply for opportunities to obtain short-term and eventually long-term compensation.

My ikigai is to educate and mentor. Specifically, I love to teach at the whiteboard and to mentor medical students planning careers in internal medicine and residents planning careers in hospital medicine. In my first two years as an academic hospitalist, I built my whiteboard-teaching skillset by arranging clinical coverage to attend SHM’s Academic Hospitalist Academy, and then by creating a novel chalk talk for each week as an attending. At the same time, I applied and was accepted for a position on SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

These early efforts helped build my reputation as a medical educator and mentor and culminated in a teaching award. In my third year, I applied to and was accepted into the Student Teaching Attending program. This provided me with a stipend to teach medical students in the afternoons—my first compensation. During off weeks, and after hours, I continued to pursue faculty development opportunities to demonstrate my commitment to medical education and trainee mentorship.

In my fourth year, I applied to and was accepted into a medical education fellowship, based on a proposal to implement a whiteboard teaching faculty development curriculum at my institution. This opportunity provided me with 20% full-time equivalent compensation, in the form of both funding and protected time.

Putting in the hard work to develop your mission and passion and to demonstrate its value to key stakeholders at your institution will pave the way for eventual compensation and synthesis of profession and vocation, the remaining cornerstones of ikigai.

Dr. Patel (@buckeye_sanjay) is the associate program director and clerkship site director of internal medicine at Riverside Methodist Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. Dr. Sansbury is the transitional year program director, associate program director of internal medicine, and medical director of the Grand Strand Health Education and Simulation Center at Grand Strand Health, Myrtle Beach, S.C. Dr. Ganith (@RashmiGMD) is an assistant professor of clinical medicine, assistant director of wellness of hospital medicine, and preliminary clinical track director at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio. Dr. Nelson (@RyanENelsonMD) is an instructor of medicine and the associate site director for Core-I Medicine Clerkship at Harvard Medical School/Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

This content is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training Committee, which submits content to The Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early-career hospitalists.