As hospitalists, we encounter heart failure (HF) regularly, but we have all seen it documented in a variety of ways (congestive HF (CHF), acute on chronic HF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), etc.). While all these diagnoses possess clinical validity, there’s a very specific way we need to document HF to accurately capture our patients’ severities of illness and risks of mortality while also optimizing our hospitals’ lengths of stay (LOS), quality metrics, and reimbursements. Before delving into the specifics of heart failure documentation, we need to first understand two important concepts in clinical documentation and coding: principal diagnosis and secondary diagnosis(es).

As hospitalists, we encounter heart failure (HF) regularly, but we have all seen it documented in a variety of ways (congestive HF (CHF), acute on chronic HF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), etc.). While all these diagnoses possess clinical validity, there’s a very specific way we need to document HF to accurately capture our patients’ severities of illness and risks of mortality while also optimizing our hospitals’ lengths of stay (LOS), quality metrics, and reimbursements. Before delving into the specifics of heart failure documentation, we need to first understand two important concepts in clinical documentation and coding: principal diagnosis and secondary diagnosis(es).

Principal Dx and secondary Dx

According to the Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (UHDDS) definition,1 the principal diagnosis is “that condition established after study to be chiefly responsible for occasioning the admission of the patient to the hospital for care.” Secondary diagnoses are all additional conditions that affect patient care in terms of requiring any of the following: clinical evaluation, therapeutic treatment, diagnostic procedures, extended LOS, or increased nursing care or monitoring.

Dr. Velasquez

Our clinical documentation improvement and coding partners use the principal and secondary diagnoses from our notes to determine which specific diagnosis-related group (DRG) within a cluster of DRGs a patient belongs to. Each specific DRG has an expected LOS and relative weight (RW). The expected LOS is the average amount of time a patient is expected to require hospital care for a particular diagnosis, and the RW is a surrogate marker for the expected intensity of care and resource utilization for a particular diagnosis. So, a patient assigned to a DRG with a higher LOS and RW is expected to require longer hospitalization and more resource utilization, which translates to a more favorable reimbursement for our hospital system.

Example 1: A 70-year-old patient with diabetes mellitus type II, peripheral vascular disease, and poorly controlled hypertension is admitted to the hospital for dyspnea, moderate left pleural effusions, and hyponatremia with a sodium of 127. The admission history and physical lists dyspnea as the principal diagnosis. A brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) test and echocardiogram are ordered as part of the workup, and the patient is started on a trial of intravenous diuresis. The following day, the BNP results are found to be significantly elevated, and the echocardiogram reveals an ejection fraction of 60% with grade II diastolic dysfunction. The attending physician adds acute diastolic HF as a new diagnosis to their assessment and plan, and the patient is discharged once medically optimized.

In this scenario, even though dyspnea was the main reason the patient presented to the hospital, the underlying etiology of this patient’s signs and symptoms that resulted in their hospital admission was acute diastolic HF. So, acute diastolic HF would be the principal diagnosis, as long as it’s been consistently documented in the attending’s notes.

Example 2: A 65-year-old patient with hypertension, diabetes mellitus type II, and hyperlipidemia presents to the hospital with chest pain and shortness of breath. She’s found to have elevated troponin, ST depressions in the lateral leads on the electrocardiogram, an elevated BNP, mild pulmonary edema on chest X-ray, and oxygen saturation of 87% on room air. She is admitted to the hospital for treatment of a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and heart failure. Her echocardiogram reveals an ejection fraction of 40% with wall motion abnormalities. She undergoes left heart catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention to the left circumflex artery and is diuresed for her first two days of hospitalization. Her cardiac medications are optimized, and she is euvolemic and chest pain-free by the time of discharge.

In this scenario, the principal diagnosis would be the NSTEMI since it was the condition that was primarily responsible for the hospitalization. Acute systolic HF (or acute heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF]) would be a secondary diagnosis because it was evaluated and treated during the hospitalization but was not the chief reason for hospitalization.

HF as a principal diagnosis

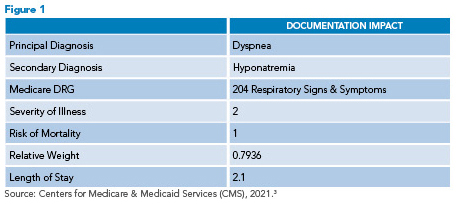

In example 1, the history and physical lists dyspnea as the principal diagnosis. This is understandable, as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms and initial presentation were unclear. Upon further investigation, though, we find that this patient actually has acute diastolic HF, which is the underlying etiology of their dyspnea, pleural effusion, and hyponatremia.2 Appropriately identifying and documenting HF as a principal diagnosis assigns this patient to the most appropriate DRG for quality metrics and reimbursement.2 In Figure 1, we see the expected LOS and RW for this patient if the attending consistently documented dyspnea as the principal diagnosis and never updated their notes to identify that the patient has heart failure.

In example 1, the history and physical lists dyspnea as the principal diagnosis. This is understandable, as the etiology of the patient’s symptoms and initial presentation were unclear. Upon further investigation, though, we find that this patient actually has acute diastolic HF, which is the underlying etiology of their dyspnea, pleural effusion, and hyponatremia.2 Appropriately identifying and documenting HF as a principal diagnosis assigns this patient to the most appropriate DRG for quality metrics and reimbursement.2 In Figure 1, we see the expected LOS and RW for this patient if the attending consistently documented dyspnea as the principal diagnosis and never updated their notes to identify that the patient has heart failure.

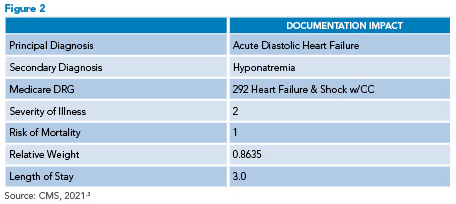

In Figure 2, we see a positive change in LOS and RW when the attending appropriately documents that the patient has acute diastolic heart failure. It’s important to remember that knowing you’re treating a patient for HF without documenting heart failure in your note does not translate to improved metrics. We must document heart failure for our patients to be assigned to the appropriate heart failure DRG.

In Figure 2, we see a positive change in LOS and RW when the attending appropriately documents that the patient has acute diastolic heart failure. It’s important to remember that knowing you’re treating a patient for HF without documenting heart failure in your note does not translate to improved metrics. We must document heart failure for our patients to be assigned to the appropriate heart failure DRG.

HF as a secondary diagnosis

Secondary diagnoses are all conditions outside the principal diagnosis that impact a patient’s care. Secondary diagnoses are just as vital to document as the principal diagnosis because they help our clinical documentation improvement and coding partners assign our patients to the appropriate DRG. HF as a secondary diagnosis is particularly impactful as it often serves as a complication or comorbidity (CC) or a major complication or comorbidity (MCC), which assigns our patients to a DRG with a higher LOS and RW. When documenting HF as a secondary diagnosis, the two most important components to remember to document are the type and acuity of HF.

Type and acuity of HF

The different types of HF to specify in your documentation are systolic HF, diastolic HF, or combined systolic and diastolic HF. Depending on your practice, you may want to document HFrEF or HFpEF, which are also acceptable alternatives.4 For acuity, it’s important to specify whether a patient’s HF is acute, chronic, or acute on chronic. You can also use terms like “decompensated” or “exacerbation” as synonyms for acute.5

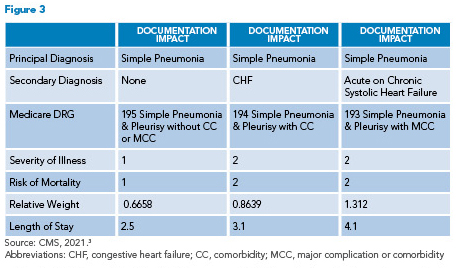

Example 3: An 82-year-old male with systolic HF presented to the hospital with a three-day history of fevers, cough productive of green phlegm, and shortness of breath. He has a left lower lobe opacity on a chest X-ray and is admitted to the hospital for bacterial pneumonia. During exam in the emergency department, he’s also found to be volume overloaded. He is treated for pneumonia, diuresed with intravenous Lasix for two days, and discharged on day three with oral antibiotics and diuretics. In this scenario, pneumonia is the principal diagnosis and HF is a secondary diagnosis, so documenting the type and acuity of HF is key. Figure 3 illustrates the impact of specific HF documentation.

Example 3: An 82-year-old male with systolic HF presented to the hospital with a three-day history of fevers, cough productive of green phlegm, and shortness of breath. He has a left lower lobe opacity on a chest X-ray and is admitted to the hospital for bacterial pneumonia. During exam in the emergency department, he’s also found to be volume overloaded. He is treated for pneumonia, diuresed with intravenous Lasix for two days, and discharged on day three with oral antibiotics and diuretics. In this scenario, pneumonia is the principal diagnosis and HF is a secondary diagnosis, so documenting the type and acuity of HF is key. Figure 3 illustrates the impact of specific HF documentation.

Failure to document CHF as a secondary diagnosis assigns this patient to DRG 195. Documenting CHF assigns them to DRG 194 and documenting acute on chronic systolic HF assigns them to DRG 193. Capturing the type and acuity of HF by documenting acute on chronic systolic HF moves this patient into the highest weighted DRG.

You might be wondering how this affects your daily practice or why you should change your documentation habits. Consider the fact that most C-suite executives are using LOS and case mix index (CMI) as metrics to gauge our efficiency and productivity as a hospitalist group and as independent providers. CMI is simply the sum of all the RWs for all the DRGs our patients fall into divided by the number of patients we treat in a given time period. A higher CMI represents a sicker patient population that uses more resources. Being able to affect LOS and CMI by learning how to document our patient’s diagnoses accurately is one of the most powerful ways we have to represent the stellar care we provide our patients every day.

Key Takeaways

- It’s reasonable to list a diagnosis of dyspnea, pleural effusion, or acute respiratory failure initially while evaluating a patient. However, if the patient is found to have HF as a principal diagnosis, it’s important to document this so that the most appropriate DRG for quality metrics and reimbursement is assigned.

- Even if HF ends up being a secondary diagnosis, it’s still vital to document it since it assigns our patients to the appropriate DRG and can affect expected LOS and RW.

- Acceptable ways of documenting the type of HF include systolic HF, diastolic HF, or combined systolic and diastolic HF. HFrEF or HFpEF are also acceptable alternatives. “CHF” alone is too non-specific.

- For acuity, document whether the HF is acute, chronic, or acute on chronic. Terms like “decompensated” or “exacerbation” can be used as synonyms for acute.

Dr. Velasquez is an assistant professor of medicine in Emory’s division of hospital medicine. He serves as a hospitalist and physician advisor at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Atlanta.

References

- Health information policy council; 1984 revision of the Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set–HHS. Notice. Fed Regist. 1985;50(147):31038-40.

- American Hospital Association. Acute congestive heart failure with diastolic or systolic dysfunction. In: ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic, First Quarter ICD-10 2017. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2017:46.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS-1752-F, Table 5: Hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long term care hospital prospective payment system and policy changes and fiscal year 2022 rates. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/zip/fy2022-ipps-fr-table-5-fy-2022-ms-drgs-relative-weighting-factors-and-geometric-and-arithmetic-mean.zip. Published August 13, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- American Hospital Association. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. In: ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic, First Quarter ICD-10 2016. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2016:10-11.

- Pinson R, Tang C. CDI Pocket Guide. 15th ed. Houston, TX: Pinson & Tang, LLC; 2022.

Enjoyed this article and it provided some great information. I did have a question about the other chronic conditions noted like diabetes in example 2. Will this condition also be coded as a secondary diagnosis?