Case

A 76-year-old man with a medical history of congestive heart failure (CHF) with left ventricular ejection fraction of 30%, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and recent hospitalization for CHF exacerbation comes to the emergency department (ED) complaining of dyspnea, orthopnea, and progressively worsening edema in the lower extremities. His current medications include furosemide 40 mg PO daily, lisinopril 20 mg PO daily, and Coreg 25 mg PO daily. The patient wants to know what to do to avoid coming to the ED frequently.

Heart failure in the hospital

Dr. Pinzon

There are three important goals to achieve in our patients during hospitalization due to CHF.

The first goal is decongestion, regardless of the ejection fraction (EF). The second goal is the initiation of recommended long-term therapies. In patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced EF, there is a controversy between stepwise treatment versus shotgun treatment. The third goal is the continuity of care once the patient is discharged, with a transition goal of preventing re-congestion regardless of the EF.

The hallmarks of HF hospitalization with any EF are symptoms and signs of congestion; treatment; and response to intravenous (IV) diuretics. The principal symptoms of HF with preserved EF are dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, abdominal discomfort, and edema. The patient can also experience trouble concentrating and exertional fatigue. Most symptoms and hospitalizations are due to congestion. Once the patient is hospitalized, the focus in all HF with any EF is to relieve the congestion with preservation of adequate perfusion and blood pressure. Once the patient is stabilized, the next step is to evaluate for a guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), including a diuretic plan, for long-term disease modification. The use of a diuretic treats most symptoms. The neurohormonal systems are highly activated, which means that neurohormonal antagonists are very effective to decrease hospitalization.

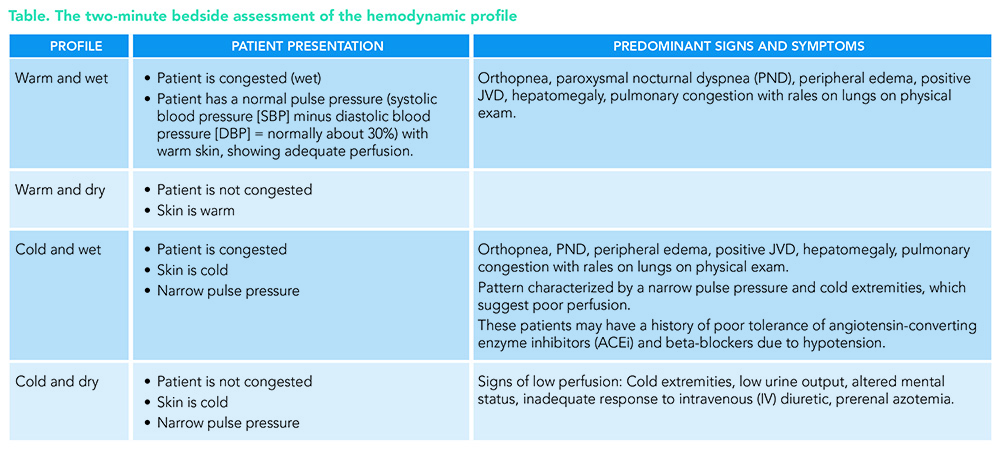

The key is the initial bedside evaluation for hemodynamic profiles, i.e., congestion versus low perfusion, and their combinations: cold and dry, cold and wet, warm and dry, and warm and wet (see Table). The recommendations are to evaluate the severity of the congestion and adequacy of perfusion as well as the common precipitating factors and the overall patient trajectory to guide appropriate therapy.

One important recommendation is to check the blood pressure manually, which will give us an accurate narrow pulse pressure. A proportional pulse pressure <25% of SBP suggests low stroke volume unless the patient is very tachycardic. Beware of overestimation of blood pressure by automated cuffs when the pulse is irregular (patients with atrial fibrillation or frequent premature ventricular contractions). Evidence of low perfusion includes narrow pulse pressure and cool extremities, a patient who seems to be sleepy or obtunded, and labs that can show elevated lactic acid (>2.0 mmol/L) and hyponatremia.

About 85 to 90% of HF hospitalizations are patients with a profile of warm and wet. The predominant symptoms are orthopnea, edema, and jugular vein distention (JVD) on physical exam, showing us the patient is congested (wet), and has a normal pulse pressure (systolic blood pressure minus diastolic blood pressure/systolic blood pressure, normally about 30%) with warm skin, showing an adequately perfused patient (warm).

The degree of congestion for a patient with HF on admission predicts the hospital length of stay but does not predict outcomes such as readmission or death after discharge. The risks of readmission or death after discharge depend on the success of decongestion achieved in the hospital.

Medical treatment

The decongestion strategy includes recommendations for diuretics in hospitalized patients. Patients with HF admitted with evidence of significant fluid overload should be treated promptly with an IV loop diuretic to improve symptoms and reduce mortality.

Therapy with diuretics and other GDMTs should be titrated to resolve clinical evidence of congestion and reduce symptoms and the risk of rehospitalization.

When therapy with diuretics is inadequate to relieve symptoms and signs of congestion, it is reasonable to intensify the diuretic regimen, using either a higher dose of IV loop diuretics or the addition of a second diuretic.

The right dose of the diuretic is the dose that works for the patient. In diuretic-naïve patients, the dose is usually 40 mg IV daily. In patients who are receiving diuretics as outpatients, the starting dose as an inpatient is the total doses of diuretics per day, given IV at least twice per day. If the patient is on a high dose and also metolazone, the metolazone can be added to the loop diuretic during inpatient treatment.

Escalation of the loop diuretic during hospitalization

If the diuretic dose is working but you want more total output, increase the frequency.

If the diuretic dose is not effective double the dose.

If diuretic dose is at >200 mg IV, consider adding metolazone. Another possibility to consider is bolus plus diuretic infusion.

Try to avoid low-dose dopamine or dobutamine, although these can be added if the reversible condition is likely to improve. Dopamine or dobutamine can trigger atrial fibrillation or accelerated rate, ventricular arrhythmia, and ischemia. These medications are not effective in HF with preserved EF, and most importantly, these medications are hard to wean a patient from in advanced HF with low EF.

It is important to remember that any residual congestion increases the risk of readmission, and any degree of residual congestion predicts death. If we have to send patients out wet, we should expect to see them again.1

Not every patient can get dry, especially patients with dominant right ventricular failure, patients with cardiorenal syndrome with very high blood urea nitrogen, patients with edema related to low oncotic pressure or compromised venous and lymphatic drainage, patients with consistently unrecorded high fluid intake or the salt cheater, and those patients who are approaching the end of the journey. For patients requiring diuretic treatment during hospitalization for HF, the discharge regimen should include a plan for adjustment of diuretics to decrease rehospitalizations.

What is new for heart failure in the hospital?

In patients with HF with reduced EF, the current practice is multiple GDMTs for long-term disease modification, including a diuretic plan. After stabilization, the focus is on enhancing the GDMT. Begin with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and/or angiotensin receptor blockers, then beta-blockers. The next step is to add mineralocorticoid antagonists for selected patients with good renal function and potassium excretion. Another addition to the treatment of HF is the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

Practical use of Entresto

Sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) is a combination angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi), the first in its class. It simultaneously inhibits neutral endopeptidase and the renin-angiotensin system. If the patient is taking ACEi, this medication should be stopped for 36 to 48 hours to avoid angioedema. The starting dose is 24/26 mg unless the patient is on a high dose of ACEi or has hypertension. Do not perform more than one upwards titration in the hospital, and most importantly, make sure the patient can afford this medication. There is an unexplained quality of life improvement for some patients, and this could be associated with an effect on endorphin metabolism. The most common side effects are dizziness, unexpected renal dysfunction, and documented 25% incidence of hypotensive events if the baseline SBP is ≤110. ARNi is not a recommended therapy in patients with an SBP <100, HF class IV, and/or advanced HF.2

Recommendations for the use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (RASI: ACEis and ARBs) and ARNi

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in whom ARNi is not feasible, treatment with an ACEi or ARB provides high economic value.

ARNi is recommended for patients with HFrEF and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II to III symptoms, as this medication reduces morbidity and mortality.

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic HFrEF, the use of ACEi is beneficial to reduce morbidity and mortality when the use of ARNi is not feasible.

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic HFrEF, who are intolerant to ACEi because of cough or angioedema, and when the use of ARNi is not feasible, the use of ARB is recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality.

In patients with chronic symptomatic HFrEF NYHA class II or III who tolerate an ACEi or ARB, replacement by an ARNi is recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality further.

ARNi should not be administered concomitantly with ACEi or within 36 hours of the last dose of an ACEi. ARNi and ACEi should not be administered to patients with any history of angioedema.3

Recommendations for the use of SGLT2 inhibitor for heart failure with reduced EF

In patients with symptomatic chronic HFrEF, SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are recommended to reduce hospitalization for HF and cardiovascular mortality, irrespective of the presence of type 2 diabetes.3

New clinical trial for recommendations for the use of ivabradine

Ivabradine is a new therapeutic agent that selectively inhibits the pacemaker current, If, in the sinoatrial node, providing heart rate reduction. Ivabradine can be beneficial to reduce HF hospitalization for patients with symptomatic HF NYHA class II-III, stable chronic HFrEF with a left ventricular EF (LVEF) less than or equal to 35%, who are receiving guideline-directed evaluation and management including a beta-blocker at the maximum tolerated dose, and who are in sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 70 bpm or greater at rest.3,4

Vericiguat is recommended for patients with HF NYHA Class II-IV, LVEF <45%, recent HF hospitalization or IV diuretics, and elevated BNP levels.4,5

Digoxin is a purified glycoside extracted from digitalis lanata and was discovered in 1785 by William Withering. The Digitalis Investigation Group trial6 showed a decrease in hospitalization rate in patients with advanced heart failure. The trial consistently showed an increase in hospitalization rate after digoxin was stopped. Digoxin is the only medication you can use in decompensated HFrEF to decrease heart rate with atrial fibrillation. It is helpful to initiate when weaning from low-dose IV inotropes. Digoxin may support treatment when trying to initiate HF therapies with borderline blood pressure. You should halve the dose when amiodarone is started. Safety levels are 0.07 to 0.10 nanograms/mL.

Integration of care: transitions and team-based approaches

In patients with high-risk HF, particularly those with recurrent hospitalizations for HFrEF, referral to a multidisciplinary HF disease management program is recommended to reduce the risk of hospitalization.

In patients hospitalized with worsening HF, patient-centered discharge instruction with a clear plan for transitional care should be provided before hospital discharge. In patients being discharged after hospitalization for worsening HF, an early follow-up, generally within seven days of hospital discharge, is reasonable to optimize care and reduce rehospitalization.

Re-evaluate long-term treatment and summarize patient and family education. Prescribe activity and exercise, and consider HF exercise rehab referral and a discharge follow-up appointment in 7-14 days. Hand-off goes to outpatient providers, with early follow-up caller and home health visits and triage to return to the ED.

Application of the Data to Our Case

For our patients, the clinician should re-evaluate long-term treatment plans. Lisinopril can be discontinued and Entresto can be added as a new medication, and the provider can consider adding SGLT2 inhibitors to reduce hospitalization and cardiovascular mortality during hospitalization. Clinicians should prescribe activity and exercise and consider HF exercise rehab referral and a discharge follow-up appointment in 7-14 days. During the hand-off, transition patients to their outpatient physicians with early follow-up calls and home health visits, and triage to return to the ED if needed.

Bottom line

Establish a diagnosis of HFrEF, address congestion, and initiate a GDMT: ARNi in NYHA II-III; ACEi or ARB in NYHA II-IV; beta-blocker, MRA, SGLT2i, and diuretics as needed.

Consider additional therapies once GDMT is optimized: Ivabradine for NYHA II-III, HFrEF, NSR with an HR greater than or equal to 70 bpm on maximally tolerated beta-blocker; Vericiguat for NYHA II-IV LVEF <45%, recent HF hospitalization or IV diuretics, elevated BNP levels; digoxin for symptomatic HFrEF; polyunsaturated fatty acids for NYHA II-IV; and potassium binders for patients with HF with hyperkalemia while taking renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.

In heart failure with preserved EF, almost all hospitalizations are also due to congestion, and diuretic therapy for congestion treats most symptoms. Neurohormonal antagonism has minimal impact on symptoms or hospitalization. The recommendation for treatment is diuretics and SGLT2i. ARNi can be used in symptomatic HF with LVEF ±50% (level 2B recommendation).7

Mid-range heart failure patients are considered those who are recovering from HFREF. LVEF is between 41 and 49%. The recommendation for these patients, especially if they have a previous LVEF <40%, is that they should remain on their full regimen, adjusting doses as necessary, to avoid volume depletion, other symptomatic hypotension, or major side effects.

If the patient is at or near target weight before the day of discharge, the focus is on the transition day from IV to PO. Most patients admitted with HF congestion need to go home with diuretics.8 Diuretic prescription at discharge decreases readmissions and mortality.

Key Points for Bedside HF Evaluation

- The two-minute bedside assessment of hemodynamic profile includes right-side signs: orthopnea, elevated jugular vein distention, edema (25%, more often in older patients), pulsatile hepatomegaly, and ascites.

- On physical exam, determine the presence of rales (which are rare in chronic HF), louder S3, increasing mitral and tricuspid regurgitation murmurs, and labs showing elevated BNP/NT-proBNP higher than the patient’s baseline.

- Manually check blood pressure; this gives an accurate narrow pulse pressure. A proportional pulse pressure <25% of systolic blood pressure (SBP) suggests low stroke volume unless the patient is very tachycardic.

- Beware of overestimation of blood pressure by automated cuff when the pulse is irregular (typically in patients with atrial fibrillation or frequent premature ventricular contractions). Evidence indicating low perfusion includes narrow pulse pressure; cool extremities; a patient who seems to be sleepy or obtunded; and labs that show elevated lactic acid >2.0 and hyponatremia.

References

- Ambrosy AP, et al. Clinical course and predictive value of congestion during hospitalization in patients admitted for worsening signs and symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: findings from the EVEREST trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(11):835-43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs444.

- Böhm M, et al. Systolic blood pressure, cardiovascular outcomes and efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: results from PARADIGM-HF. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(15):1132-1143.

- American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, Heart Failure Society of America. Heart Failure Guideline. https://accmedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Heart-Failure-Guideline-PR_FINAL.pdf. Published online Apr 2022. Accessed 5/19/22.

- Swedberg K, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):875-85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1.

- Armstrong PW, et al. Vericiguat in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1883-1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915928.

- The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525-533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801.

- Packer M, et al. Heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: a side-by-side examination of the PARAGON-HF and EMPEROR-Preserved Trials. Circulation. 2021;144:1193-1195 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056657.

- Cox ZL, Stevenson LW. The weight of evidence for diuretics and parachutes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(6):680-683. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.044.

Excellent article on the assessment and management of HF in hospitalized patients.