Case

Mr. Smith is a 48-year-old man with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and compensated cirrhosis who presented to the emergency department with alcohol withdrawal. He had been consuming one pint of vodka daily for the past three months but tried to quit. The next morning, he felt unwell and came to the hospital. On presentation, he was hemodynamically stable but was disoriented to time and complained of nausea, headache, and tremors. He appeared diaphoretic and had visible tremors in outstretched hands. Initial laboratory investigations showed stage 1 acute kidney injury, but were otherwise unremarkable, with normal transaminases. He received IV hydration and was started on symptom-based benzodiazepine protocol based on Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol (CIWA) scores.

Brief overview of the issue

AUD is prevalent in the U.S. with approximately one-fifth of persons aged 12 or older reporting binge alcohol use in the past month.1 Alcohol is also the most common cause of substance-related emergency department (ED) visits.2 Alcohol acts as a central nervous system depressant by increased release of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) with its action on GABAA receptors and its antagonism at N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.3 Withdrawal symptoms after discontinuation of alcohol use result from a decrease in GABA and an increase in NMDA pathway neurotransmission. Benzodiazepines are the first-line treatment for alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) and are efficacious in reducing the severity of symptoms, delirium tremens, and seizures.4 However, commonly used benzodiazepine-only regimens require close monitoring and frequent redosing. Large cumulative total doses may be required to achieve sufficient symptom control, which increases the risk of adverse effects such as sedation or respiratory depression. Concurrent medical conditions, such as chronic liver disease which may coexist with AUD, may also limit the use of benzodiazepines in certain patients. Additionally, benzodiazepines alone may not adequately treat all symptoms in some episodes of AWS. Therefore, familiarity with other medications as alternative or adjunct therapy for AWS is beneficial for hospitalists.

Overview of the data

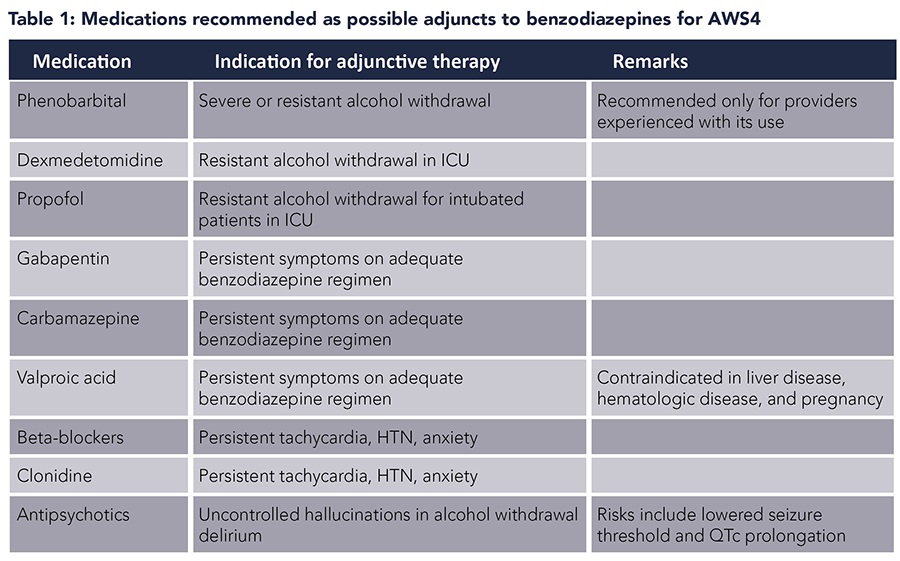

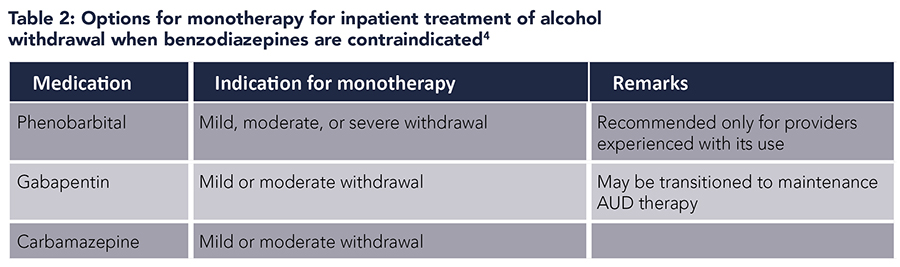

Phenobarbital. Phenobarbital, a barbiturate, acts on GABAA receptors and has been used for the treatment of AWS. Phenobarbital also inhibits NMDA receptors, which may provide additional benefit in AWS. Several studies have reported that phenobarbital is an effective alternative to benzodiazepines in AWS.5-8 In an uncontrolled prospective study of ED patients with AWS, phenobarbital used alone was effective in improving symptoms.5 A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial found no difference in ED length of stay or symptom control with the use of phenobarbital versus benzodiazepines.6 Two studies among hospitalized patients also reported phenobarbital to be an effective alternative to benzodiazepines.7,8

Phenobarbital has also been used as an adjunct to benzodiazepines in AWS. It has been postulated that phenobarbital and benzodiazepines have additive effects on AWS due to differential action on GABAA receptors. While phenobarbital prolongs the duration of chloride channel opening, benzodiazepines increase the frequency of opening. Clinical findings in published literature bear this out. In a retrospective study of ED patients, single-dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-triggered benzodiazepines was associated with a shorter length of stay and no significant difference in the number of adverse events.9 A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in ED patients reported that the use of single-dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-guided benzodiazepines was associated with decreased total benzodiazepine dose and fewer ICU admissions with no significant difference in the number of adverse events.10

A systematic review concluded that barbiturates were safe and effective in the treatment of AWS.11 Combination of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines could be used to decrease ICU admissions and mechanical ventilation. A beneficial role of phenobarbital was also suggested in severe AWS and benzodiazepine-refractory AWS. It is recommended that phenobarbital be used only by providers who have experience with this medication.4

Gabapentin. Limited small-scale studies suggest that gabapentin may be efficacious in the management of mild AWS in ambulatory settings. Gabapentin may have benefits in terms of decreased daytime sedation and decreased alcohol craving.12 However, alcohol withdrawal seizures in patients treated with gabapentin have been reported in several studies.13,14 Therefore, gabapentin monotherapy should not be used in severe AWS or in those with a history of AWS seizures or who are at risk for progression to severe AWS. The use of gabapentin as an adjunct to symptom-triggered lorazepam was also not shown to improve outcomes in one open-label retrospective study.15

Carbamazepine. Studies have demonstrated some efficacy of carbamazepine in the treatment of AWS, with one meta-analysis showing that carbamazepine was superior to benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal symptoms.16 Compared to benzodiazepines, carbamazepine presents less risk of sedation and misuse, and is an option for monotherapy in the ambulatory setting for mild AWS when there is a low risk for the development of severe withdrawal.4 In the inpatient setting, carbamazepine is an option for monotherapy for mild or moderate alcohol withdrawal if benzodiazepines are contraindicated. It can also be used as an adjunctive treatment for persistent symptoms in patients treated with benzodiazepines.4

Dexmedetomidine. Dexmedetomidine is an intravenous central-acting alpha-2 adrenergic agonist which has been suggested as an adjunct to benzodiazepines in AWS in critical care settings. Besides producing light sedation without respiratory depression, dexmedetomidine has anxiolytic and sympatholytic properties that reduce autonomic hyperactivity, qualities that support its use in AWS. In patients with AWS and delirium, the addition of dexmedetomidine to benzodiazepine has been shown to decrease delirium severity.17 It may also reduce total benzodiazepine dose requirements in the short term, though the difference seems to be lost when analyzed over the total duration of hospital stay.18 Dexmedetomidine may also decrease the need for mechanical ventilation and associated complications such as nosocomial infections.19 The effect on length of stay is debatable with some studies reporting shorter ICU and hospital stays, whereas others noted longer hospital stays.19,20 An important consideration would be cost and resource utilization since it can only be used in a critical care setting. With current evidence, the use of dexmedetomidine seems beneficial in a select group of patients in a critical care setting with severe AWS, or in those with delirium, to decrease the need for mechanical ventilation due to high benzodiazepine requirements.

Propofol. Propofol is a dose-dependent sedative-hypnotic with agonism of GABA receptors through a site different from that of benzodiazepines, and inhibition of NMDA subtype of glutamate receptor. Due to its mechanism of action, propofol has been used in AWS in critical care settings as an adjunct to benzodiazepines. In patients with refractory AWS, the addition of propofol is associated with decreased benzodiazepine dose requirement. Studies have reported similar or increased duration of mechanical ventilation, time to resolution of symptoms, and ICU stays with propofol adjunct.21 Thus, propofol may be beneficial as an adjunct in a select group of patients with AWS refractory to benzodiazepines who are in a critical care setting and requiring mechanical ventilation, or if other adjuvant medications are contraindicated. Hypotension, hypertriglyceridemia, and propofol-related infusion syndrome are possible adverse effects of propofol use.

Beta-blockers and clonidine. Beta-blockers and the alpha-2 agonist clonidine may be a reasonable adjunctive treatment for the management of persistent tachycardia and hypertension for patients who are adequately treated with benzodiazepines and who have received adequate fluid and electrolyte replacement.4 These medications may improve anxiety as well. Neither of these medication classes is adequate as monotherapy.

Antipsychotics. Antipsychotics are not recommended as a stand-alone therapy for alcohol withdrawal. Antipsychotics may be reasonable as an adjunctive treatment to benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal delirium with uncontrolled hallucinations and agitation.3 Antipsychotics reduce the seizure threshold and thus must be used with caution and close monitoring in the setting of alcohol withdrawal.

Valproic acid. Valproic acid is not recommended as a monotherapy for alcohol withdrawal due to insufficient evidence.22 It can be used as an adjunctive treatment to benzodiazepines.4 Its use is contraindicated in the setting of liver disease, hematologic disease, and pregnancy.

Baclofen. Baclofen is not recommended for the treatment of AWS.4 A systematic review of randomized controlled trials yielded no conclusions regarding the use of baclofen for AWS.23

Ethanol. The efficacy of ethanol for treating AWS is unknown, and it has recognized adverse effects. Ethanol is not recommended for the treatment of AWS.4

Application of the data to the original case

Based on his CIWA scores, Mr. Smith received 75 mg oral chlordiazepoxide, and subsequently also received 1 mg intravenous (IV) lorazepam. He became somnolent but arousable, though he seemed to be oriented only to self. Due to his cirrhosis and concern for poor clearance of benzodiazepine, the CIWA-based benzodiazepine protocol was discontinued, and he received IV phenobarbital 260 mg followed by IV phenobarbital 130 mg at re-evaluation in one hour. On subsequent evaluations, Mr. Smith’s symptoms improved. The next day he noted the resolution of all symptoms but started to have alcohol cravings and requested medications for craving control to assist with alcohol abstinence. He was provided with a prescription for gabapentin and was discharged with a planned follow-up with a primary care provider. Of note, on his previous admissions for alcohol withdrawal, he had been treated with the CIWA-based benzodiazepine protocol and had a longer length of stay in hospital (three to seven days).

Bottom line

The use of alternative and adjuvant drugs to benzodiazepines may be considered in select patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Quiz:

A 43-year-old female with a past medical history of alcohol use disorder presents to the emergency department with tremors and malaise after discontinuing her usual alcohol intake of eight beers daily. She is diagnosed with alcohol withdrawal syndrome and treated with a symptom-triggered benzodiazepine regimen, thiamine, and intravenous fluids. She develops alcohol withdrawal delirium with significant agitation. What is the best next step in management?

a. Switch to phenobarbital monotherapy

b. Add haloperidol

c. Increase benzodiazepine dosing

d. Add propofol

Answer: C. Increase benzodiazepine dosing. Benzodiazepines are the first-line treatment of alcohol withdrawal delirium. Large doses may be required, and the initial step in management should be to titrate dosing to control symptoms and agitation while closely monitoring for adverse effects such as oversedation. Phenobarbital monotherapy is an alternative to benzodiazepines, but benzodiazepines are the preferred first-line option; in this case, there is no apparent contraindication to continuing benzodiazepine therapy. Phenobarbital could be used as an adjunctive agent if control of symptoms with benzodiazepines is inadequate. Haloperidol is not an option as monotherapy for alcohol withdrawal delirium, but its addition as an adjunctive treatment can be considered for agitation or hallucinations inadequately controlled with benzodiazepines. In this case, ensuring adequate dosing of benzodiazepines would be prudent before adding haloperidol. Haloperidol and other antipsychotics also can lower the seizure threshold and prolong the QTc. Propofol may be required for resistant alcohol withdrawal but would generally require intubation. If this patient were to experience resistant withdrawal on benzodiazepines, propofol might be considered; ensuring adequate benzodiazepine dosing should be done first.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2011MHFDT/2k11MHFR/Web/NSDUHmhfr2011.htm. Published 2012. Accessed February 5, 2021.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.DAWN Alcohol Profile. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/dawn-drug-abuse-warning-network. Published 2020. Accessed February 5, 2021.

- Schuckit MA. Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens). N Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2109-2113.

- The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. J Addict Med. 2020;14(3S Suppl 1):1-72.

- Young GP, et al. Intravenous phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and convulsions. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16(8):847-850.

- Hendey GW, et al. A prospective, randomized, trial of phenobarbital versus benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(4):382-385.

- Tidwell WP, et al. Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome: Phenobarbital vs CIWA-Ar Protocol. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27(6):454-460.

- Hjermø I, et al. Phenobarbital versus diazepam for delirium tremens—a retrospective study. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(8):A4169.

- Ibarra F, Jr. Single dose phenobarbital in addition to symptom-triggered lorazepam in alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(2):178-181.

- Rosenson J, et al. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(3):592-598.e592.

- Mo Y, et al. Barbiturates for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: A systematic review of clinical trials. J Crit Care. 2016;32:101-107.

- Leung JG, et al. The role of gabapentin in the management of alcohol withdrawal and dependence. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(8):897-906.

- Myrick H, et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(9):1582-1588.

- Stock CJ, et al. Gabapentin versus chlordiazepoxide for outpatient alcohol detoxification treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):961-969.

- Andaluz A, et al. Fixed-dose gabapentin augmentation in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a retrospective, open-label study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(1):49-57.

- Minozzi S, et al. Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(3):Cd005064.

- Woods AD, et al. The use of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to benzodiazepine-based therapy to decrease the severity of delirium in alcohol withdrawal in adult intensive care unit patients: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(1):224-252.

- Mueller SW, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose range study of dexmedetomidine as adjunctive therapy for alcohol withdrawal. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1131-1139.

- Ludtke KA, et al. Retrospective review of critically ill patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal: dexmedetomidine versus propofol and/or lorazepam continuous infusions. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(3):208-213.

- Beg M, et al. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome with and without dexmedetomidine. Perm J. 2016;20(2):49-53.

- Brotherton AL, et al. Propofol for treatment of refractory alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(4):433-442.

- Malcolm R, et al. Update on anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Am J Addict. 2001;10(s1):s16-s23.

- Liu J, Wang LN. Baclofen for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8(8):Cd008502.

Dr. Shekhar

Dr. Pal

Dr. McFarland

Dr. McFarland is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine, at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Shekhar is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Pal is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, N.M.