Advocating for immigration reform

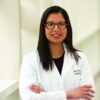

A lack of transparency and information in the beginning of the pandemic significantly contributed to anxiety, said Anuradha Amara, MD, MBBS, a hospitalist in Wilmington, Del. She felt that what was on the news and what was actually going on in the hospitals were quite different. Colleagues were getting sick, there wasn’t enough personal protective equipment, and planning went out the window. “It’s like a meteor hitting a place and then we start dealing with the aftermath, but we weren’t ready before,” Dr. Amara said. “We didn’t have a plan for a pandemic.”

Then there was the concern of either her or her husband, a cardiologist, getting sick and potentially losing their jobs and immigration status. “How am I going to go back to my country if I had to? What will happen to my family if I die? If I go on the ventilator? Those are the insecurities we found additional to the pandemic challenges we had,” Dr. Amara said.

Not being able to go see their family in India or have them come visit was difficult – “it was pretty bad up there,” said Dr. Amara. Fortunately, her family members in India remained safe, but there’s a very real uneasiness about returning should an emergency arise. “Should I go back and then take the risk of losing my job and losing my position and my kids are here, they’re going to school here. How do you decide that?” she asked.

One of the worst effects of her visa restrictions was not being able to help in New York when hospitals were so short-staffed, and the morgues were overflowing. “New York is 3 hours away from where I live, but I was in chains. I couldn’t help them because of these visa restrictions,” Dr. Amara said. During the emergency, the state allowed physicians from other states to practice without being licensed in New York, but immigrant physicians were not included. “Even if we wanted to, we couldn’t volunteer,” said Dr. Amara. “I have family in New York, and I was really worried. Out of compassion I wanted to help, but I couldn’t do anything.”

Before the pandemic, Dr. Amara joined in advocacy efforts for immigrant physicians through Physicians for American Healthcare Access (PAHA). “In uncertain times, like COVID, it gets worse that you’re challenged with everything on top of your health, your family, and you have to be worried about deportation,” she said. “We need to strengthen legislation. Nobody should suffer with immigration processes during an active pandemic or otherwise.”

In the United States, 28% of physicians are immigrants. Dr. Amara pointed out that these physicians go through years of expensive training with extensive background checks at every level, yet they’re classified as second preference (EB-2) workers. She believes that physicians as a group should be excluded from this category and allowed to automatically become citizens after 5 years of living in the United States and working in an underserved area.

There have been an estimated 15,000 unused green cards since 2005. And if Congress went back to 1992, there could be more than 220,000 previously unused green cards recaptured. These unused green cards are the basis behind bills H.R.2255 and S.1024, the Healthcare Workforce Resiliency Act, which has been championed by SHM and PAHA. “It will allow the frontline physicians, 15,000 of them, and 25,000 nurses, to obtain their permanent residency,” said Dr. Amara. “These are people who already applied for their permanent residencies and they’re still waiting.”

SHM has consistently advocated for the Act since it was first introduced, written multiple letters on the issue, and supported it both on and off Capitol Hill. The society says the legislation would be an “important first step toward addressing a critical shortage” in the U.S. health care system by “recognizing the vital role immigrant physicians and nurses are playing in the fight against COVID-19.”

Currently, SHM has a live action alert open for the reintroduced bill, and encourages members to contact their legislators and urge them to support the reintroduction of the Act by cosponsoring and working to pass the legislation

Dr. Amara encourages physicians to start engaging in advocacy efforts early. Though she didn’t begin participating until late in her career, she said being aware of and part of policies that affect medicine is important. If more physicians get involved, “there are so many things we can take care of,” said Dr. Amara. “The medical profession doesn’t have to be so difficult and so busy. There are ways we can make it better and I believe that. And obviously I’ll continue to work and advocate for the entire medical profession, their problems, their health and well-being, to prevent burnout.”

© Frontline Medical Communications 2018-2021. Reprinted with permission, all rights reserved.