It is not clear that all of the increase in stroke risk is a direct effect of POAF. Indeed, in a retrospective analysis of almost 3,000 CABG patients, 1.1% suffered a stroke during their hospital stay. Fewer than half of those had a cardiac rhythm other than sinus rhythm. In the 15 stroke patients who developed POAF, nine presented with stroke symptoms prior to the first episode of AF.9 The authors suggest that aggressive anticoagulation for POAF would not have prevented most of these events.

Furthermore, the rate of in-hospital stroke after non-cardiac surgery is probably much lower, though it has not been as well studied. These data raise some questions as to the benefit of anticoagulation in the immediate postoperative period, though it is difficult to draw firm conclusions without randomized data.

What about non-cardiac surgery? There is less evidence available for patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, but the few studies that do exist also point to higher stroke risk in patients with POAF. A large population-based study using ICD codes found that the one-year risk of stroke for patients with POAF after non-cardiac surgery was 1.47% compared to 0.36% in non-cardiac surgery patients without POAF (P<0.001). Based on these data, the long-term stroke risk after POAF in non-cardiac surgery patients is similar to that of medical AF patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2. The authors of this study suggest that transient POAF after non-cardiac surgery may carry a long-term stroke risk similar to any other AF diagnosis.10 However, this study design is subject to significant ascertainment bias (i.e., they may have unintentionally captured some patients with preexisting or prolonged AF), and further research is needed to better delineate this risk.

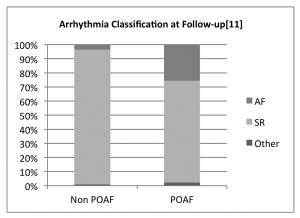

Does increased stroke risk translate into increased mortality? In a retrospective study of 17,000 patients, El-Chami et al found that POAF after CABG was associated with decreased survival after one year (90% versus 96%) and 10 years (55% versus 70%).11 However, those patients who develop POAF may be sicker overall.

Another study showed that death due to stroke occurred in 4.2% of POAF patients compared to 0.2% of non-POAF patients in a five-year period.12 Based on these studies, POAF is likely associated with increased mortality, but there may be other unaccounted variables. Nevertheless, the increased mortality associated with POAF in these populations is similar to that seen for non-surgical population-based studies13 and provides support that those with newly diagnosed AF in the post-surgical setting should at least be followed closely to assess for recurrence.

What is a patient’s risk of developing atrial fibrillation later in life? When we choose to anticoagulate patients with POAF, we then have to determine whether they should be committed to long-term anticoagulation. It is thought that many cases of POAF are transient; however, some patients will go on to have persistent or paroxysmal AF after discharge.

A retrospective study examined 571 patients who underwent CABG, 30% of whom had POAF during the index admission. After five years of follow-up, 25% of those with POAF were diagnosed with paroxysmal or persistent AF after discharge compared to only 3% of patients without POAF. Researchers did this by looking at the most recent ECG, if done in the last year, or by obtaining a new ECG at the five-year point.12 By this method, it is probable that some diagnoses of paroxysmal AF were missed.

In another study of about 300 CABG patients, about 20% of patients with POAF also went on to develop post-discharge AF, defined as symptomatic AF that led to medical evaluation. As in the previous study, it is likely that there were undetected episodes of AF.14 Thus, in cardiothoracic surgery patients, some but not all of whom develop POAF have recurrent or ongoing AF. For this reason, if anticoagulation is started, it may be reasonable to stop anticoagulation after weeks or months if ongoing AF is not apparent.