Some of the most important lessons I’ve learned in life have come from conversations with my patients. Such was the case with Ms. W a wiry 85-year-old who came in with increasing fatigue and a frightening CT scan.

Some of the most important lessons I’ve learned in life have come from conversations with my patients. Such was the case with Ms. W a wiry 85-year-old who came in with increasing fatigue and a frightening CT scan.

“The results of the blood tests and CT scan have me concerned,” I had told her. “I am worried you might have an immune system cancer, lymphoma.”

Taking her hands and meeting her gaze with what I hoped was a tender smile, I concluded, “This might sound scary, but we have an awesome team to be at your side as we figure this out, and I believe this is something we can beat as a team.”

Surprisingly, she met my smile with one of her own and said, “Oh Jesus, your love and the love of this doctor will heal me. Praise the power of love and praise the power of God!”

“Wow,” I thought, “My love? Not my intent but certainly feels like a healthy response to this bad condition. Maybe I should be thinking more explicitly about love and its role in healthcare”

So, then I had to ask myself what is love anyway, in medicine and in the rest of life. And can it actually heal?

It’s ironic something that seems so fundamental can be enigmatic at the same time. Love is so important yet hard to talk about. I have had to lean on experts to appreciate our misunderstanding of love and verify its importance.

Here are four ways to think about love as a hospitalist:

Love is more and less than you think. When most of us think of love, we first think of romantic passion, finding our “one and only”. Beyond that, we might think of the unconditional lifelong bonds that hold families together.

But could love even be more than that? How do emotion scientists understand this conundrum? Psychologists like Barbara Fredrickson suggest we focus on our body’s, rather than our culture’s, idea of love. She describes love as “micro-moments of warmth and connection you share with another living being.”

More specifically, love is shared a positive emotion with briefly shared biochemistry and behavior—and leads to care for the well-being of the other. What distinguishes love from other positive emotions is the sensory connection to another–voice, sight, or touch–and the coming together of tone of voice, facial expression, or gestures. There is mirrored behavior, warmth, and well-wishing, all happening in a few moments. Think of it as simply friendliness with a little warmth.

Emotions by their nature are fleeting. According to Fredrickson, love only happens with these encounters— but what builds with repeated episodes over time is an ease of reconnecting that promotes trust and enduring commitments. These bonds are what we typically think of as love. These bonds are powerful and essential for human flourishing, but distinct from the fleeting emotion of love.

Love is the warmth we can feel with that person behind the lunch counter, in the hallway with colleagues, and importantly, our patients with whom we share even a short conversation.

Summoning Ms. W when I meet a new a patient, I see it as an opportunity to spread a little love, to express warmth and friendliness which leads us to care about each other, and, critically, we build the trust needed to better guide their care.

In short, love can be low stakes and everywhere—but the most important thing about it is that love can build the bonds that help us on our journeys.

Focusing on our body’s idea of love gives us more opportunities to love. I believe that the more we understand and talk about this broader, friendlier, lighter version of love, the easier it is to disentangle it from the more complicated romantic and familial relationships and bonds we associate with love.

Love is foundational for health. Air, food, water. What’s next? Love. The anthropologist William Goldschmidt says we are born with “affect hunger.” We have a need—a hunger—for positive interpersonal emotions just as we do for more material nutrients.

We know the data on emotionally deprived children: when “foundling” children of past eras were taken and then given adequate food and shelter without emotional nurturance, they died in infancy at 10 times of rate of other kids.

Recently some researchers have focused on the lack of love in later stages of life. Many studies in multiple countries now demonstrate that a lack of social interactions is associated with shortened lifespan. While these studies don’t talk about love, per se, we can imagine that many of these social interactions would meet our definition of love–micro-moments of connection and warmth we share with one another.

Does that make sense biologically? For social creatures like us who have depended on a group for safety, we can experience unwanted isolation as a threat to survival. With time hypervigilance develops that paradoxically makes it harder to have of moments of warmth and connection. As Kathi Heffner and her colleagues have documented, over a 20-year period, isolation, and stress (as manifest in C-reactive protein level) were associated with an increased rate of MI.

Interestingly, when we do connect, we activate the parasympathetic nervous system and as a result, we become more trusting and cooperative. These connections result in our ability to express a more diverse behavioral repertoire. With small positive interactions, bit by bit, we develop the cognitive, behavioral, and social resources we need for a healthy productive life. Barbara Frederickson calls this phenomenon the “broaden-and-build” framework of love—and now a decade of research supports this idea.

We can learn to experience more love. The broaden-and-build theory suggests an upward spiral where a little love provides us, and unconsciously teaches us, to generate more love. Are there ways to jump-start this virtuous spiral?

Clinical trials have demonstrated that a form of mindfulness meditation called loving-kindness meditation increased daily experiences of positive emotions and, in turn, produced increases in a wide range of personal resources such as purpose in life and social support. Depressive symptoms decreased as well.

In many observational studies, daily spiritual practices of many kinds are strongly associated with increased positive emotions.

For those of us disinclined to pick up a formal spiritual practice, I suspect that less formal practices might work. Simply practicing a friendly kindness and seeing all our interactions as an opportunity to bring nourishing moments of love to our lives will likely help us find love more readily.

Healthcare providers should embody and promote love as a healing force and essential for healthy living.

Is it unrealistic to believe that hospitalists can talk about love? Not this lighter, ubiquitous version of love, not when it is essential for the health of our patients. Certainly not when working with students and residents. They should not have to learn for themselves over a 20-year period as I have done. We should teach them it is these “positive micro-moments” that fill our tanks on our busy days and promote the healing of our patients.

For those who are ready, I believe we need to demonstrate love in the way we engage with our staff, colleagues, and patients–bringing a warm, friendliness to our body language, tone of voice, and words. Most of us bring friendliness to our interactions. Yet, I have found that doing this with intentionality – thinking, I am bringing a little love to this interaction – makes it more powerful.

Importantly, by using the word love with others, we can demonstrate we understand its crucial role in health. Fortunately, the term “spread the love” is widely used and gives us the language we need to do this.

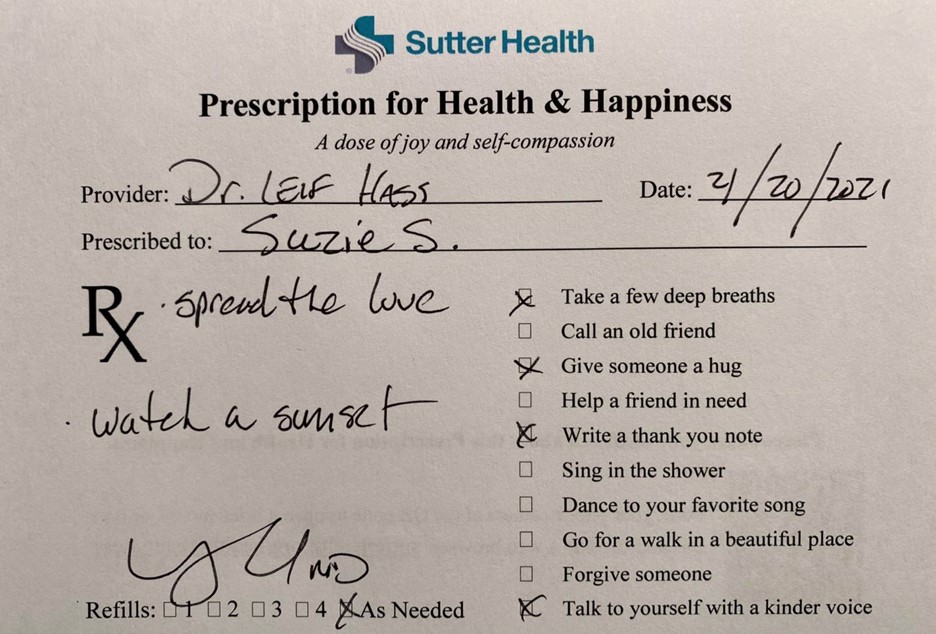

Given the health consequences of lovelessness, it should be best practice for hospitalists to prescribe activities that promote love and connection. When my patients leave the hospital, I routinely give out handwritten “prescriptions for health and happiness” along with prescriptions for statins and diuretics. I prescribe “spread the love” to almost everyone and say that “love makes you live longer and spreading kindness to those around you will do as much for your health as some of the medicines you will be taking.” More concrete prescriptions might involve joining a church choir or volunteering with Meals on Wheels, for those for whom that is possible. One of my heroes, Dr. Naomi Rachel Remen, believes that “service is the best cure for loneliness,” and I agree.

My nursing colleagues are deeply moved to see physicians recognize this important but underappreciated part of their profession. Nursing units can be transformed if we lead by example in our daily interactions and with conversations at huddles on the importance of love in healing and well-being. Patient experience will improve if as a team we recognize the critical role love plays in our lives.

Indeed, I see a focus on love as one of the next steps in the evolution toward a more holistic and patient-centered form of medicine.

In his beautiful song “Jesus, etc.”, Jeff Tweedy of the rock band Wilco says, “Our love is all of God’s money”. The line has been a revelation for me. Put another way, love is our superpower; it is our special gift that allows us to create the relationships that weave the fabric of our society. Without it, robots could be trying to take over our jobs.

Dr. Hass is a hospitalist at Sutter East Bay Medical Group in Oakland, Calif. He is a member of the clinical faculty at the University of California, Berkeley-UC San Francisco joint medical program, and an adviser on health and health care at the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.