Case

An 86-year-old female with a history of metastatic pancreatic cancer and diabetes was admitted for chest pain and dyspnea and found to have an acute pulmonary embolism. The hospital course was complicated by gastric outlet obstruction. She continued to decline despite maximal medical intervention and required intravenous hydromorphone every two hours and scheduled intravenous antiemetics every six hours, despite a nasogastric tube to suction. The patient lacked the capacity to make medical decisions, so her son was assigned durable power of attorney. During goals-of-care conversations, the patient’s son felt this ongoing management was inconsistent with the patient’s wishes and agreed with shifting focus to comfort. The hospitalist consulted the inpatient hospice team to assess if the patient was appropriate for general inpatient (GIP) hospice.

Hospitalists and palliative care specialists at our health system regularly provide end-of-life care for patients, including symptom control and management of physical and psychosocial stressors. Patients with a life expectancy of six months or less are eligible to enroll in home hospice care at discharge, benefiting from care by a holistic and specialty-trained interdisciplinary hospice team. Similarly, GIP hospice provides holistic end-of-life care and family support in acute-care hospitals. Patients who are appropriate for GIP hospice services often have a life expectancy of hours to days, require care that cannot be delivered at home, and have symptoms that are difficult to control in any other setting.

GIP hospice is an important option to offer patients and families facing end-of-life decisions. Our practitioners recognize the importance of providing a seamless transition to GIP hospice care so patients and families can receive appropriately specialized support at the end of life.

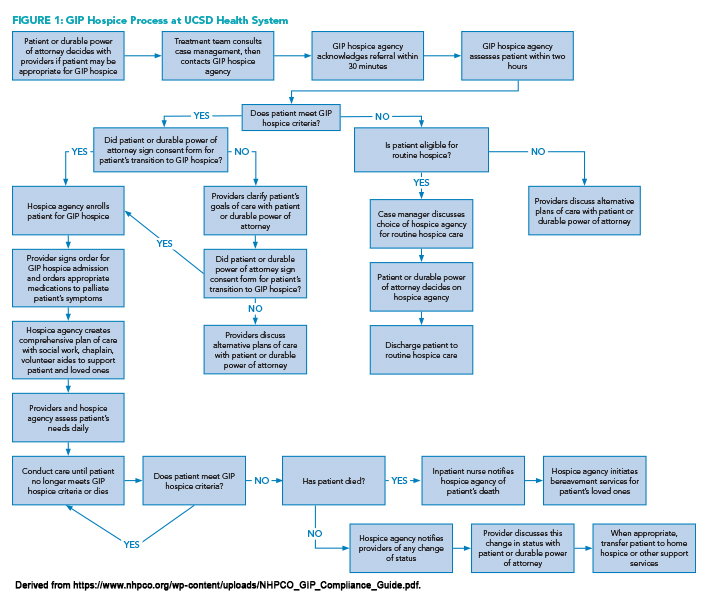

At our hospital, we encourage ongoing goals-of-care discussions throughout a patient’s hospital stay to facilitate understanding of their current condition, options for and risks of possible treatments, discussion of personal goals, and symptom management. Following these discussions, if the patient, or their agent under a durable power of attorney, should express interest in learning more about hospice, the treating provider can order an inpatient case management consultation to review available hospice resources, determine if hospice services can be provided in the home, or if hospice services would be provided more appropriately in the hospital under GIP hospice level of care (see Figure 1).

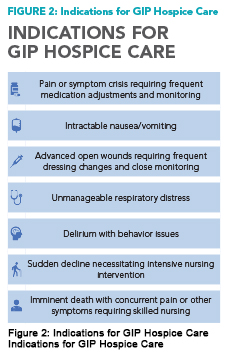

After the patient is evaluated by a registered nurse hospice liaison (RNHL) and is determined to meet eligibility criteria for GIP hospice level of care (see Figure 2), the RNHL requests signed consent from the patient or durable power of attorney to provide inpatient hospice services. The treating physician then completes a GIP hospice order set to address commonly encountered symptoms and to flag the patient as having GIP hospice status. The RNHL will then work closely with the patient’s treatment team to ensure the plan stays focused on patient comfort and end-of-life goals.

After the patient is evaluated by a registered nurse hospice liaison (RNHL) and is determined to meet eligibility criteria for GIP hospice level of care (see Figure 2), the RNHL requests signed consent from the patient or durable power of attorney to provide inpatient hospice services. The treating physician then completes a GIP hospice order set to address commonly encountered symptoms and to flag the patient as having GIP hospice status. The RNHL will then work closely with the patient’s treatment team to ensure the plan stays focused on patient comfort and end-of-life goals.

Under GIP hospice care, patients are continually evaluated for changes in their clinical condition and symptoms. Patients who become clinically stable or no longer require close adjustment of their symptom management plan may be transferred home or to a lower level-of-care facility while continuing to benefit from hospice services.

Whether or not patients decide to enroll in GIP hospice, symptoms are assessed and palliated via specific order sets that include medications for symptom management, non-medical comfort interventions, and assistance from palliative psychiatrists, social workers, case managers, and clergy. Additionally, these order sets remind providers to address symptoms common in patients at the end of life, including pain, delirium, respiratory distress, nausea, and complex wound care, and to discontinue unnecessary labs, artificial nutrition, vital signs, and cardiac monitoring, and equipment such as defibrillators and pacemakers.

Setting up a GIP hospice program

Creating our GIP hospice program began with partnering with a hospice agency known for its ethical process, quality of care, and established leadership. At the same time, our hospital also agreed to provide ongoing support for a palliative-medicine fellowship that includes a hospice experience.

The hospice agency assigns RNHLs and social workers to our medical center seven days a week to work alongside clinical teams and to ensure appropriate and timely referrals. Hospice RNHLs can access the electronic health record (EHR) and can contact frontline providers using EHR-based secure messaging.

Ongoing training for physicians, residents, advanced practice providers, nurses, and medical students across multiple service lines allows maintenance of this knowledge and provides an opportunity for feedback. This successful collaborative effort has been sustained for six years.

Outcomes and future directions

Our 86-year-old female with metastatic pancreatic cancer transitioned to GIP hospice. She was moved to a private room once one was available, transitioned to a hydromorphone drip, and was visited by the chaplain. Per family request, all labs were discontinued, cardiac monitoring was stopped, and vital sign measurements were minimized. She passed comfortably three days later.

Since the integration of GIP hospice into our health system six years ago, we have noted several positive results, including:

A 30% increase in placement of appropriate patients into GIP hospice from 2021 to 2022, followed by a further 10.5% increase in appropriate GIP placements from 2022 to 2023.

Earlier and more regular discussions on goals of care and advance care planning during each patient-care journey. Our hospital added an “advance care planning” note type in our EHR.

A reduction in length of stay from time of hospice consult to discharge home.

Future directions for our hospice collaboration include continuing education about GIP hospice to all clinical specialties in our health system, a proposal to lease hospice beds from a local skilled nursing facility for patients stable for hospital discharge but unable to go home, and development of a rapid escalation pathway for liaisons and clinicians to respond to sudden clinical changes in GIP hospice patients.

Bottom line

Creating a GIP hospice workflow with an ethical, collaborative, and trustworthy partner hospice agency has allowed our health system to manage terminally ill patients proactively and reduce associated costs (e.g., re-hospitalizations and emergency department use), while also providing patients with a higher quality of life and a greater sense of dignity at the end of life.

Key Points

- Hospice emphasizes quality, not quantity, of life in patients whose life expectancy is six months or less.

- GIP hospice is appropriate for patients who have a life expectancy of hours to days with care that cannot be delivered at home.

- Creation of an inpatient, comfort-care, order set can help providers determine appropriate treatment options as well as interventions which may be appropriate to stop.

Dr. Frederick

Ms. Smith

Ms. McSpadden

Dr. Childers

Dr. Huang

Dr. Ally

Ms. Akhondzadeh

Ms. Dolopo-Simon

Dr. Clay

Dr. Frederick was a clinical associate professor of medicine, physician advisor, and hospitalist at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Health in San Diego and is now the physician advisor medical director at Stanford Health Care in Palo Alto, Calif. Ms. Smith is the director of post-acute care at UCSD Health in San Diego. Ms. McSpadden is the president and chief executive officer of The Elizabeth Hospice in Escondido, Calif. Dr. Childers is a clinical associate professor of medicine, physician advisor, and hospitalist at UCSD Health in San Diego. Dr. Huang is a clinical professor of medicine, physician advisor, and hospitalist at UCSD Health in San Diego. Dr. Ally is a clinical associate professor of medicine, physician advisor, and hospitalist at UCSD Health in San Diego. Ms. Akhondzadeh is a clinical quality improvement specialist in quality and patient safety at UCSD Health in San Diego. Ms. Dolopo-Simon is the director of the clinical documentation improvement program at UCSD Health in San Diego. Dr. Clay is a health sciences clinical professor of medicine and associate chief medical officer at UCSD Health in San Diego.

Quiz

Which of the following symptoms may be managed by GIP hospice?

A. Uncontrolled pain

B. Delirium

C. Respiratory distress

D. Intractable nausea

E. Complex wound care

F. All of the above

Correct option: F—all of the above. Indications for GIP hospice can include any, or a combination, of these symptoms in patients whose life expectancy is hours to days and whose care cannot be delivered in a setting other than an inpatient setting.

Transition to GIP hospice requires consent by the patient or their agent under a durable power of attorney.

A. True

B. False

Correct option: A—true. If a patient meets the criteria for GIP hospice care and the patient or their durable power of attorney agent agree to transition care to GIP hospice care, then the registered nurse hospice liaison requests a signed consent from the patient or their durable power of attorney agent to provide inpatient hospice services.

Great read! I found it interesting that implementation of a GIP hospice program at UCSD resulted in reduction of LOS from time of hospice consult to discharge home. I imagine this is largely driven by integration of RNHL’s into the care team and timely management of EOL symptoms.