SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee (PMRC) members debut a new column in The Hospitalist—“Demystifying Performance Measures.” This series intends to provide members with a framework for assessing commonly used measures in performance-based compensation programs. In each article, we’ll review one commonly used measure identified by the PMRC. Measure selection is based on group consensus and major measure categories from the biannual State of Hospital Medicine Report. The measures undergo comprehensive review and summary by a subset of members of the PMRC and are then approved for publication by the broader committee. SHM regularly comments on publicly reported measures under consideration or active measures reviewed regularly by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the National Quality Forum.

Measurement programs are the reality of the majority of hospital medicine programs. Providing hospitalists perspectives in measure definitions and measure strengths and limitations equips them to build more meaningful measurement programs and engage in dialogue with executive leaders. We envision this column to empower hospitalists to communicate the “why,” create a respectful and transparent environment for discussion and innovation among all team members, emphasize collaborative improvement, identify tools and resources to aid in improving performance, establish trust in the process, and think critically about the data we review and are held accountable to daily.

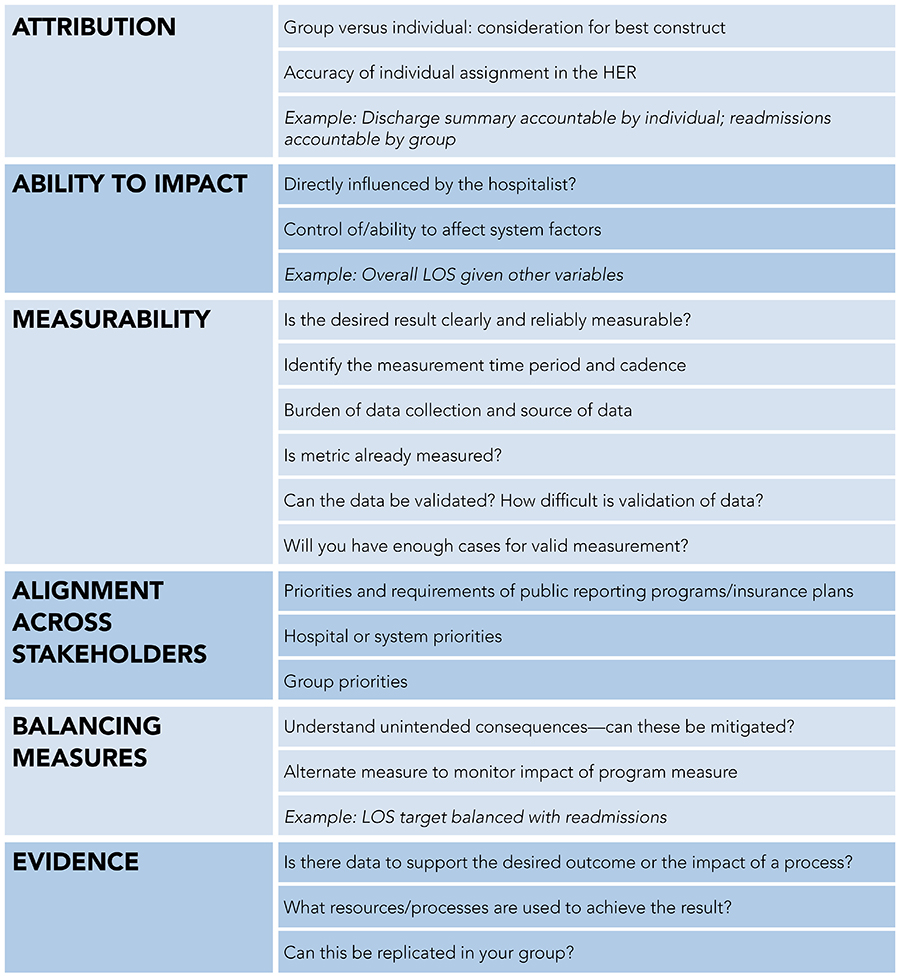

Each measure will be structured under the same review rubric including the following domains, as applicable: Attribution, impact factor, measurability, alignment across stakeholders, balancing measures, and evidence. The graphic below provides more details about the domains.

Each measure will be structured under the same review rubric including the following domains, as applicable: Attribution, impact factor, measurability, alignment across stakeholders, balancing measures, and evidence. The graphic below provides more details about the domains.

Wise performance-measurement strategies focus attention on clinical processes linked to improved care of patients, while also advancing the mission of health systems. Inpatient screening and treatment of substance use disorder is an example that aligns with available evidence and is likely to result in numerous downstream benefits. Characteristics of the best performance measures are those that are patient-centered, have a direct link between measure performance and patient or system outcome, and are clearly attributable to the care provided by the hospitalist. Few measures meet these requirements, so individuals and groups need a measures-based paradigm to best inform practice. Through this discussion, we hope to help foster the development of meaningful measurement programs by hospitalists and institutional leadership.

In this first article we’ll explore the strengths and limitations of discharge before noon (DCBN), a performance metric regularly used to assess hospitalists. DCBN is a common performance metric driven by hospital systems and is an example of a measure where direct attribution and impact by the hospitalist are not clear, and which has limited evidence supporting a positive impact on care.

Case

John Doe is hospitalized for a congestive heart failure (CHF) exacerbation and is now ready for discharge but has multiple needs to achieve best practices for CHF for transitioning to home. The hospitalist has seen him, provided education, and completed the discharge paperwork, medication reconciliation, and signed the discharge order. Before the patient can be discharged, there are many outstanding items:

- Pharmacy confirmation of medication reconciliation and delivery of medications to the patient

- Rehabilitation service’s final recommendations

- CHF education by the interprofessional patient educator

- Insurance authorization and approval for home health services

- Delivery of a rolling walker and home oxygen

- Transportation home

- Final lab results

- Nursing staff to discharge him

Discussion

DCBN is one example of a frequently used measure whose clinical and operational significance can be thoughtfully debated and viewed from various perspectives. Is there a causal link between DCBN and improved patient outcomes? Does it improve hospital or emergency department (ED) overcrowding? At what time threshold should goals be set? Does DCBN matter to patients? Do certain institutional characteristics limit DCBN’s applicability? Various concerns, such as those listed above, reflect the tenuous position DCBN holds within hospital medicine performance-measurement strategies.

DCBN was envisioned as a remedy for ED overcrowding, which has been associated with worse patient outcomes, increased length of stay (LOS), and worse patient and staff experience of care.1 While computer modeling supports a direct cause-and-effect relationship between DCBN and hospital LOS and ED crowding, real-world evidence is mixed.2 One study by Wertheimer et al.1 correlated an 11% to 38% increase in DCBN with a 91-minute earlier average discharge time and the resulting shift in the median arrival time of patients to an inpatient unit from the ED from 5 p.m. to 4 p.m.1 Additional studies have correlated DCBN with increased, unchanged, and decreased LOS.3,4,5 Improvements have been demonstrated in some institutions among surgical but not medical patient populations, and vice versa.5,6

Concerns have been raised about the overreliance on DCBN as a solution to overcrowded hospitals. Hospitalists may be concerned that many requirements for discharge are beyond their control such as having care management support to arrange transportation home and durable medical equipment, available post-discharge follow-up appointments, and resourced discharge pharmacies. Patients may also feel rushed and fear they’re being discharged too soon. Focusing on DCBN as a goal may also seem counterintuitive to efforts to reduce readmissions, and insufficient attention to downstream bottlenecks that are true drivers of excess LOS leaves the impression that hospitalists need to do more. Additionally, there are concerns that adopting DCBN as a metric could lead hospitalists to keep patients who are otherwise ready for discharge in the afternoon until the following morning (although evidence is inconclusive as to whether this occurs). From an educational and professional sustainability perspective, attention to DCBN can result in concerns that safe patient care is not the hospital’s utmost priority.

The DCBN metric is largely dependent on the teamwork of many people, factors, and resources. Some of the team members who contribute to the success of this metric include but are not limited to hospitalists, consultants, nurses, patients and their families, care managers, rehabilitation services, pharmacists, environmental services associates, administrators, third-party transportation providers, post-acute care facilities, laboratory and radiology availability, durable medical equipment supply companies, health insurers, and others. Additionally, the ability of an individual hospitalist to meet this metric will be affected by the number of patients they are caring for and the complexity of the patients on their service. That said, hospitalists can help meet this metric through the time of day they see and evaluate the patient and initiate the discharge process.

DCBN has been a performance measure at one of our institutions for several years. The institutional goal is 50% and average performance has historically been approximately 50-60%. Unfortunately, there is little to no evidence to correlate these results with meaningful decreases in LOS or ED crowding. At another of our hospitals, it is not tracked at all; at a third, only 3.5% of discharge delays were found to be due to the hospitalist’s delay in seeing the patient. A balancing measure for DCBN is LOS.

Conclusion

Akin to the viewpoint offered within Readmission Reduction as a Hospital Quality Measure by Cram et al7 where the authors note that excess attention to readmissions has diminished other quality endeavors, it’s likely the undue attention to DCBN has led to improvements while also taking up bandwidth from other quality and safety endeavors that could have resulted in more meaningful benefits to patients. If we rebalance the emphasis on DCBN to resource development and validating other measures, we may see more widespread benefits to patients, hospitalists, and health care systems.

While DCBN may promote earlier discharges and reduce ED crowding, this connection is tenuous and likely dependent on the extent of adoption and whether additional throughput challenges exist that would minimize the efficacy of DCBN. Before investing in DCBN, hospital medicine groups, and hospital leadership may wish to focus on existing measures that are patient-centered, have a direct link between measure performance and patient or system outcome, and are clearly attributable to the care provided by the hospitalist. Under the right circumstances—such as where hospitals and hospital medicine groups are adequately resourced for patients to have early and safe discharges—DCBN may meet all these needs and could be adopted and monitored for effectiveness. If this metric were to be used to evaluate the performance of hospitalists, it must be individually customized to the institution and practice to better reflect individual hospitalist performance.

References

- Wertheimer B, et al. Discharge before noon: Effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-9.

- Powell ES, et al. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-96.

- James HJ, et al. The association of discharge before noon and length of stay in hospitalized pediatric patients. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):28-32.

- Kirubarajan A, et al. Morning discharges and patient length of stay in inpatient general internal medicine. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(6):333-8.

- Rajkomar A, et al. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-61.

- Rachoin JS, et al. Discharge before noon: is the sun half up or half down? Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):e246-e251.

- Cram P, et al. Readmission reduction as a hospital quality measure: time to move on to more pressing concerns? JAMA. 2022;328(16):1589-90.

Dr. Bartlett

Dr. Hegazy

Dr. Barrett

Dr. Bartlett is the associate vice chair of quality and safety, division director of inpatient operations and flow, and assistant professor at the University of New Mexico Hospital and School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M. Dr. Hegazy is an executive physician and hospital administrator who currently serves as the division chief of hospital medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, N.Y. Dr. Barrett is a rural hospitalist and faculty at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston.

The authors are members of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee, which created this series to explore quality measures common in hospital medicine.

Really informative thread.

I think it’s important to have the evidence supporting/refuting these metrics for developing an effective strategy for inpatient care. Clinical studies and articles like these also help understand complexities of such blanket measures and rather develop institution specific strategies to ultimately improve patient-care outcomes.