Case

A 23-year-old male with opioid use disorder (OUD) with intravenous use is hospitalized with a fever and several weeks of back pain. He is diagnosed with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and osteomyelitis of the cervical spine. He desires medication treatment for OUD (MOUD) but is afraid of inadequate pain management while hospitalized. During previous admissions, untreated pain and withdrawal led to in-hospital substance use.

Brief overview of issue

The opioid epidemic is increasing hospitalizations and inpatient mortality related to OUD.1 Patients with injection use can experience painful, life- or limb-threatening, infectious complications. They may delay seeking medical attention due to fear of undertreated pain and withdrawal.2 Pain management in patients with untreated OUD can be challenging given their opioid tolerance. They may need opioids many times daily to avoid withdrawal and therefore can experience significant withdrawal while waiting several hours in an emergency department (ED). Simply treating withdrawal may not meet the opioid deficit to adequately address pain. Approaches to pain management need adjustments for patients with OUD. Inadequately treated pain can increase the risk of return to use and patient-directed discharge. Opioid tolerance can decrease quickly due to the under-dosing of opioids during hospitalization, and coupled with the increasing prevalence of nonpharmaceutical synthetic fentanyl in the illicit opioid supply, can lead to a fatal overdose for patients with return to use.2 In-hospital substance use occurs in about 40% of patients with OUD, not on MOUD,3 often straining an already tenuous patient-provider relationship, and can lead to stigmatization of patients by medical staff.2 In-hospital substance use may trigger an early administrative or patient-directed discharge before adequate treatment initiation and stabilization of both the OUD and the injection-related infection, increasing risks for mortality and readmission.1 Addressing acute pain and OUD upon presentation to the hospital is critical to engage patients in care, building trust, and facilitating the completion of inpatient medical treatment for admitting diagnoses that are often due to the underlying addiction.

Overview of data

Initial pain and withdrawal management

Physicians might hesitate to start high-dose full agonists out of fear of causing sedation or overdose or due to the misperception that giving opioids will exacerbate the OUD. Acute life- and limb-threatening conditions might take priority over discussions about MOUD. The increase in nonpharmaceutical fentanyl in the illicit opioid supply is another complicating factor, and patients may be unaware of its presence. Nonpharmaceutical fentanyl is significantly more potent than heroin and has lipophilic properties, potentially complicating traditional buprenorphine initiation, especially without an approved point-of-care test assay to detect the presence of fentanyl (or any of its analogues). Buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal can occur if it is started too soon after the use of full agonists.4 If there is significant risk of precipitated withdrawal, short-acting full agonists like hydromorphone or oxycodone can be administered until a treatment plan for OUD is developed in collaboration with the patient. The benefits of engaging the patient in care and avoiding precipitated withdrawal significantly outweigh the risks of administering short-term full agonists for a patient with OUD in the hospital.2 Once pain is controlled, FDA-approved MOUD should be further discussed. Buprenorphine and methadone are safe and effective treatments for OUD that decrease cravings, mitigate withdrawal, and decrease mortality. While they provide analgesia, there are challenges to managing acute pain for patients on MOUD. A third MOUD, naltrexone, does not suppress withdrawal or provide analgesia, nor have the same mortality reduction as the other MOUDs. Patients on MOUD can receive multimodal pain control with non-opioids like acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, topical medications, and other agents when appropriate. A brief description of the three MOUDs and strategies for acute moderate to severe pain control are discussed next.

Methadone

Methadone is a full mu opioid receptor agonist and will not precipitate withdrawal if started while patients are on other full agonists. It is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor agonist and inhibitor of hERG current, which is associated with prolonged QTc by way of delayed cardiac repolarization.5,6 In the acute care setting, QTc monitoring is warranted given the prevalence of acute illness, electrolyte disturbances, and other concurrent QTc prolonging medications. These elements and methadone’s active metabolites often limit methadone titration, and the clinical adage “start low and go slow” should be applied to avoid oversedation and iatrogenic overdose.7 A typical methadone starting dose is 10 to 30 mg with no more than 40 mg on the first day while monitoring for sedation. As pain and withdrawal are adequately treated, other full agonists are tapered. In addition, clinicians should be aware of the limitations surrounding methadone as a treatment for OUD: it can only be administered by an accredited Opioid Treatment Program (OTP) after hospital discharge. Referring relationships with OTPs for continuity of care are helpful. If a patient already on methadone has acute pain in the hospital, methadone can be continued. The outpatient daily methadone dose can be split into every-eight-hour dosing while inpatient because analgesic effects typically last approximately four to eight hours.8 If needed, other short-acting full agonists can be added while monitoring for sedation. Higher doses of opioids may need to be used as such patients are not opioid naïve.9

Buprenorphine

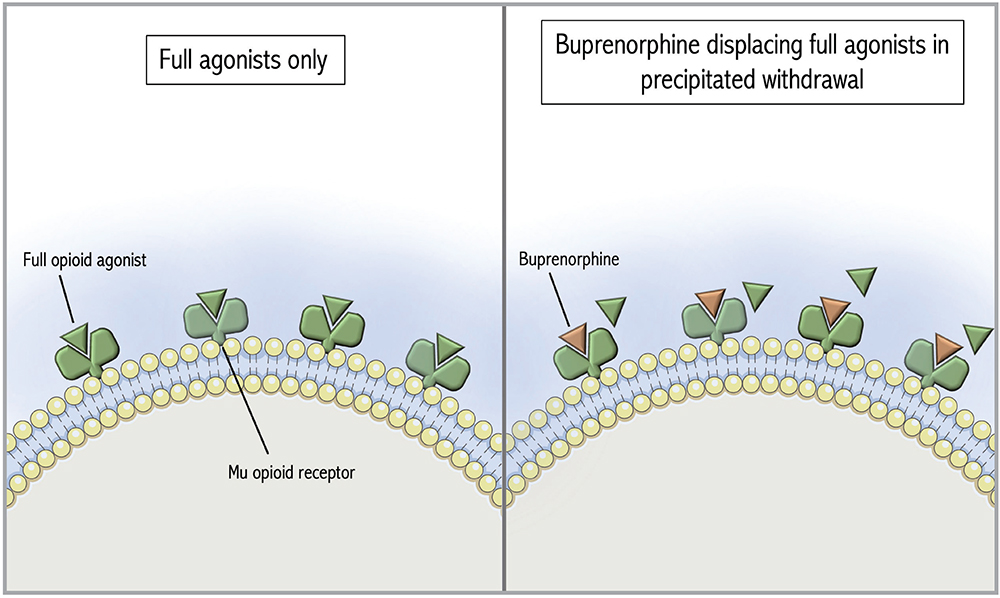

Figure 1: Mu opioid receptors occupied by full opioid agonists followed by precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine. The Figure was adapted from De Aquino and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license.11

Buprenorphine is a partial mu opioid receptor agonist with high receptor affinity that can displace full opioid agonists, potentially precipitating withdrawal (Figure 1).4 To avoid that, standard buprenorphine initiation protocols recommend patients abstain from short-acting opioids for 8 to 12 hours prior to initiation (longer if transitioning from methadone) and be in mild to moderate opioid withdrawal. If patients cannot tolerate the required period of opioid abstinence due to acute pain or withdrawal symptoms, micro-induction protocols have been developed to allow continued full agonist administration during buprenorphine initiation. In contrast to a traditional initiation, a micro-induction gradually introduces buprenorphine while the full opioid agonist is still present (Figure 2). Slow increases in buprenorphine gradually displace full agonists without causing precipitated withdrawal.10

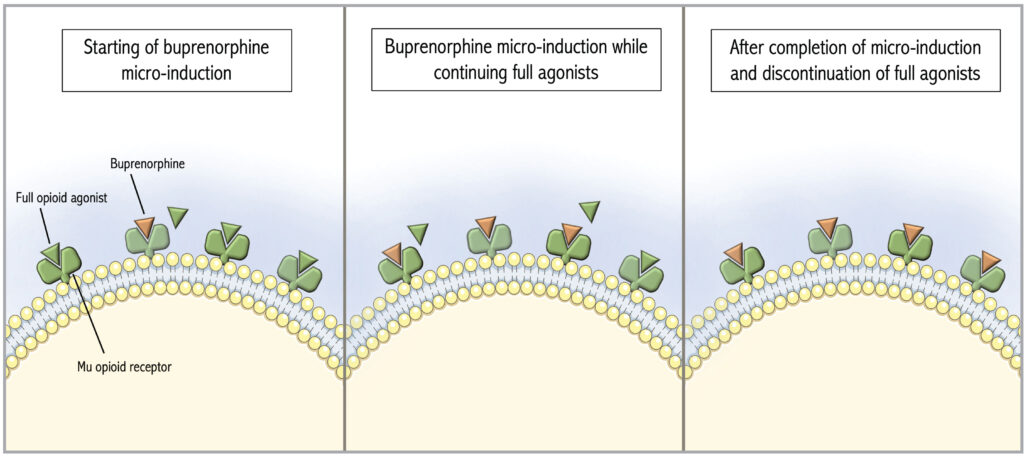

Figure 2: Activity at the Mu opioid receptor during buprenorphine micro-induction. The Figure was adapted from De Aquino and partly generated using Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license.11

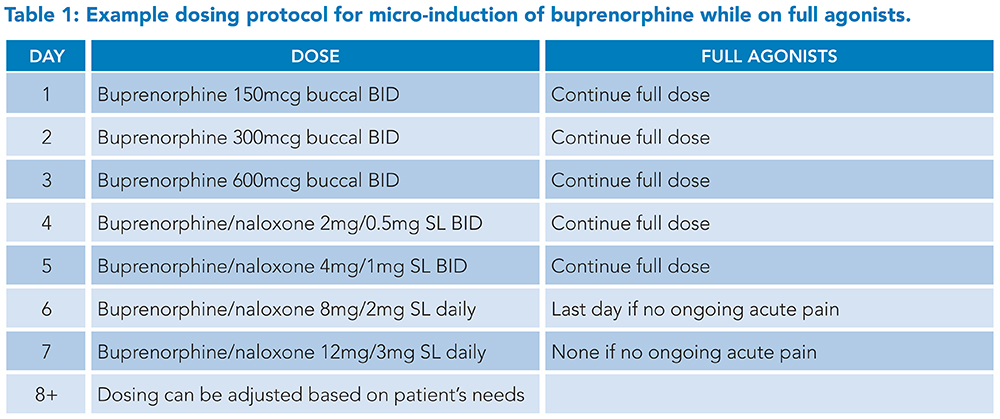

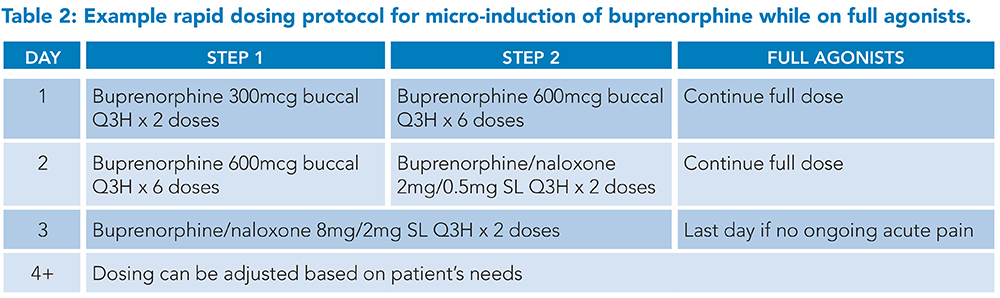

Buprenorphine buccal or transdermal patch formulations in microgram dosages are typically used for micro-induction, or the buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual films are cut into quarter or eighth pieces if allowed by hospital pharmacy policy.10 Full agonists are continued throughout the titration protocol to avoid an opioid deficit as buprenorphine doses are too small to treat withdrawal adequately. Once the low-dose protocol has been completed and acute pain has improved, full agonists can be stopped without tapering as the theory is that the patient’s receptors are now occupied by the partial agonist. Most micro-induction protocols take one week, though this is an active area of clinical research and shorter protocols are available. Examples of a week-long and a three-day protocol are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Sample protocols developed by Dr. Laura Fanucchi and the University of Kentucky Addiction Consult and Education Service and adapted from Weimer (2020) and Wong (2021).10,12

Abbreviations: BID: twice daily, SL: sublingual

Sample protocols developed by Dr. Laura Fanucchi and the University of Kentucky Addiction Consult and Education Service and adapted from Weimer (2020) and Wong (2021).10,12

Abbreviations: SL: sublingual, Q3H: every three hours

If a patient already on buprenorphine is experiencing acute pain, buprenorphine can be continued if possible, including throughout the perioperative period. Patients who are continued on buprenorphine have decreased postoperative surgical opioid requirements as well as decreased risk of withdrawal and return to use.13,14 Buprenorphine can be split for acute pain into every-six-hour dosing to maximize analgesic effect,14 and additional full agonists can provide additional analgesic effect, though opioid-tolerant dosing may be needed. This strategy also applies to patients who are on monthly injectable subcutaneous buprenorphine.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist, indicated for OUD relapse prevention. The monthly intramuscular injection is the preferred formulation due to adherence concerns. It can precipitate withdrawal, so patients should not be physically dependent when injectable naltrexone is started. This usually requires no full or partial agonists for at least 7 to 10 days, a high-risk time for overdose.15 If patients are within four weeks of receiving the injection, pain control with opioid agonists can be challenging. Analgesic modalities such as regional blocks, ketamine, and closely monitored high doses of high-affinity, high-potency opioids like hydromorphone or fentanyl can be considered to override the mu-receptor blockade.15

In-hospital use: A cardinal symptom of inadequate pain control

In-hospital illicit substance use is common2 and a symptom of a chronic medical disease (i.e., substance use disorder). Hospitalizations are stressful and can trigger drug cravings and use to relieve distress. Opioid use could also be a clue to untreated pain, withdrawal, or intense cravings. Harm reduction, instead of punishment, is more therapeutic. Patients often internalize stigma from others, which has been associated with return to use and decreased engagement with treatment.16

Application of data to the case

The patient’s initial pain and withdrawal were treated with oral oxycodone and intravenous hydromorphone. He had an episode of in-hospital illicit opioid use and was approached with a non-judgmental attitude by providers who recognize OUD as a chronic medical disease, and after discussion with the patient, concluded that the in-hospital use reflected inadequately treated OUD. There was renewed discussion about MOUD options to avoid in-hospital overdose and/or administrative discharge. A plan was made to initiate buprenorphine/naloxone using a micro-induction protocol so that full agonist opioid analgesics could continue until the acute pain subsided. There were more frequent assessments of opioid cravings, pain, and withdrawal, and close monitoring for sedation. As the acute pain from the vertebral osteomyelitis improved, a strong therapeutic alliance with the patient developed, and a dose of buprenorphine/naloxone 16 mg/4 mg was achieved over three days, without precipitating withdrawal. The patient’s pain was greatly improved, and full agonists were discontinued. Since the buprenorphine remained bound to the mu receptor, he did not experience withdrawal when the full agonists were stopped. Outpatient addiction medicine follow-up was arranged for continuation of sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone treatment.

Bottom line

Tailored strategies allow for initiation and management of medications for OUD for hospitalized patients with acute pain.

Quiz

Patients with OUD require tailored approaches to pain management when hospitalized.

1. A patient with OUD is admitted to the hospital. Their primary concern is worry and fear about experiencing opioid withdrawal. Their total clinical opioid withdrawal score (COWS) is 15, they are irritable, and they do not want to discuss MOUD options at this time. What is a good initial step to foster the therapeutic physician-patient relationship?

A. Do not offer opioids. The patient has an opioid use disorder and you do not want to make that worse.

B. Give the patient full opioid agonists. Frequently reassess for symptom control and sedation and talk about MOUD options when the patient is in less distress.

C. Offer comfort medications to treat the withdrawal such as loperamide for diarrhea and clonidine for elevated COWS.

D. No need to engage the patient in care. You suspect that they are about to leave as a patient-directed discharge, and it is unlikely anything you do will change that.

Explanation: The correct answer is B. This will control the patient’s withdrawal symptoms and allow a comfortable discussion about initiation of MOUD. This option offers the benefit of engaging the patient in care. Every hospitalization is an opportunity for patients with OUD to be engaged in their care and given an opportunity to start a mortality-reducing MOUD. While C is a common approach, comfort medications alone are unlikely to adequately relieve the patient’s withdrawal, craving, and pain. Comfort medications will not maintain opioid tolerance and will not protect against opioid overdose should the patient return to illicit use, which is common in patients with OUD who are not receiving a standard-of-care, MOUD treatment.

2. A patient with OUD is admitted to the hospital with a broken femur. The patient has been on MOUD with buprenorphine/naloxone, taking it once daily for several months. He reports that it has helped diminish his cravings for opioids, he no longer experiences opioid withdrawal and he has stopped using illicit opioids. A screening urine drug test is positive for buprenorphine, and he reports severe leg pain. How can you provide adequate pain control?

A. Stop buprenorphine/naloxone and start hydromorphone patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) immediately.

B. Continue buprenorphine/naloxone once daily without adding other medications for pain control.

C. Switch the patient to methadone starting at 60 mg daily because there is no way he can have adequate pain control while on a partial agonist like buprenorphine and he has tolerance so will need at least 60 mg methadone.

D. Continue buprenorphine/naloxone, but split it into twice or three times daily dosing and add short-acting full agonists.

Explanation: Correct answer is D. The patient is on buprenorphine/naloxone outpatient, which is consistent with his urine drug test. He reports this MOUD is helping him so the buprenorphine should be continued, if possible, to avoid destabilizing his OUD and requiring re-initiation on buprenorphine. His current dose is unlikely to relieve the acute pain he is experiencing now. Buprenorphine/naloxone can be split twice or three times daily dosing to maximize the analgesic effect and full agonists can be added and titrated as needed. Methadone dosing needs to start low and go slow even in those who are opioid tolerant to avoid iatrogenic overdose.

3. A patient with OUD is admitted to the hospital with a broken femur and severe leg pain. The patient is on MOUD with methadone. How can you provide adequate pain control?

A. Continue methadone and add short-acting full agonists.

B. Stop methadone and start a hydromorphone PCA.

C. Continue methadone without adding other medications for pain control.

D. Switch the patient to buprenorphine/naloxone.

Explanation: Correct answer is A. The patient is on methadone as an outpatient. Confirm the outpatient dose with the licensed opioid treatment program (OTP) and let the OTP know the patient is hospitalized so the patient is not considered non-adherent at the OTP, which can affect their OTP Phase status (affects the number of take-home doses and frequency of OTP visits). Continue the patient’s methadone dose during the hospitalization to avoid causing a further opioid deficit. Methadone can be split into twice or three times daily dosing to capitalize on its analgesic properties. Methadone should not be rapidly increased for acute pain as it has a long half-life and active metabolites and can cause clinically significant QTc prolongation, particularly if there are electrolyte abnormalities or other predisposing factors (not uncommon in acutely ill hospitalized patients). Short-acting agonists can be added on top of methadone to allow for pain control while closely monitoring for sedation. Buprenorphine/naloxone is contra-indicated while patients are receiving methadone because this would precipitate withdrawal.

4. A patient with OUD is hospitalized for cellulitis and an abscess secondary to injection use. They are started on hydromorphone PCA for pain control. The patient is interested in MOUD with buprenorphine but does not think that they can tolerate the pain and required a short period of mild withdrawal to start sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone. What is the next appropriate step?

A. Discontinue the PCA and wait until the patient is in mild to moderate withdrawal to start buprenorphine.

B. Offer the patient a naloxone challenge.

C. Discuss a buprenorphine micro-induction approach with the patient.

Explanation: Correct answer is C. We should involve patients in medical decision making and we have an opportunity to tailor care to the patient here by offering a tailored approach. Forcing the patient to stop the PCA for a traditional buprenorphine induction is not likely to be successful as the patient already states they cannot tolerate withdrawal. A naloxone challenge will precipitate withdrawal.

5. A patient with OUD is hospitalized for injection-related aortic valve endocarditis. The patient is not offered pain medication and is not offered MOUD. Later, the nursing staff finds injection paraphernalia and a white substance in the patient’s bed. The patient is medically stable and alert and oriented. How should you approach this patient?

A. This patient violated hospital rules by using illicit substances in the hospital. They should be administratively discharged and given a list of OUD treatment providers that they can contact.

B. This patient has a chronic medical disease that was not being treated. Go speak to the patient with a non-judgmental attitude, express concern about their health, and compassion with regards to struggling with an OUD. Discuss options with them for treating pain and withdrawal symptoms with MOUD.

C. Give the patient intravenous naloxone to avoid an overdose in the hospital. This should also precipitate withdrawal and teach the patient that it doesn’t pay to be an addict.

D. Have the patient sign a behavioral contract to not use illicit substances in the hospital again. Explain that they will be automatically discharged if they use again.

Explanation: The correct answer is B. OUD is a chronic medical disease and the patient’s potential substance use is a sign of inadequately treated OUD and pain. Inquire with a non-judgmental attitude about the patient’s current level of pain, withdrawal, and opioid cravings. C is incorrect. The patient is medically stable and there is no evidence of an opioid overdose. Naloxone will precipitate withdrawal and punishment is not an effective treatment for pain or OUD. D is incorrect because behavioral contracts can further internalize stigma, and there is no evidence that behavioral contracts improve outcomes. The patient should not be administratively discharged for in-hospital use because this behavior is a consequence of inadequate treatment of OUD and pain associated with the aortic valve endocarditis. Both are serious and life-threatening illnesses. Cessation of treatment for aortic valve endocarditis could have fatal consequences for this patient and failure to provide MOUD may also be fatal. The standard of care for treating OUD in the hospital is to offer MOUD.

Dr. South

Dr. Fields

Dr. Lofwall

Dr. Fanucchi

Dr. South is an assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, the Bell Alcohol and Addictions Scholar 2022, and works as an academic hospitalist and attending physician on the addiction consult and education service at the college of medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky. Dr. Fields is an assistant professor, department of internal medicine, and works as a hospitalist and attending on the addiction medicine and education service at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky. Dr. Lofwall is a professor of behavioral science and psychiatry, Bell Alcohol and Addictions Chair, college of medicine, University of Kentucky, and the medical director, First Bridge and Straus Clinics, Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky. Dr. Fanucchi is an associate professor, division of infectious diseases and center on drug and alcohol research, college of medicine, University of Kentucky, and the director of the Addiction Consult and Education Service, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.

Additional Reading:

Fiellin D, et al. Providers clinical support system SUD 101 core curriculum. https://pcssnow.org/education-training/sud-core-curriculum/. Accessed October 2, 2022.

Haber LA, et al. Things we do for no reason: Discontinuing buprenorphine when treating acute pain. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):633-5. doi:10.12788/jhm.3265

References

- Singh JA, Cleveland JD. National U.S. time-trends in opioid use disorder hospitalizations and associated healthcare utilization and mortality. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229174.

- Thakrar AP. Short-acting opioids for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(3):247-8. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.8111.

- Fanucchi LC, et al. In-hospital illicit drug use, substance use disorders, and acceptance of residential treatment in a prospective pilot needs assessment of hospitalized adults with severe infections from injecting drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:64-9. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.011.

- Linker A, et al. Treatment of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. The Hospitalist. 2021;25(12):2-5. https://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/249902/neurology/treatment-opioid-use-disorder-hospitalized-patients. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- Zünkler BJ, Wos-Maganga M. Comparison of the effects of methadone and heroin on human ether-à-go-go-related gene channels. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2010;10(3):161-5. doi:10.1007/s12012-010-9074-y.

- Tran PN, et al. Mechanisms of QT prolongation by buprenorphine cannot be explained by direct hERG channel block. PLoS One. 2020;15(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241362.

- Medications for opioid use disorder. Treatment improvement protocol (TIP) series 63 publication number PEP21-02-01-002. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/tip-63-medications-opioid-use-disorder. Updated 2021. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- Methadone full prescribing information. FDA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/090707orig1s003lbl.pdf. Updated April 2014. Accessed October 2, 2022.

- Agin-Liebes G, et al. Methadone maintenance patients lack analgesic response to a cumulative intravenous dose of 32 mg of hydromorphone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;226. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108869.

- Weimer MB, et al. Hospital-based buprenorphine micro-dose initiation. J Addict Med. 2021;15(3).255-7. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000745.

- De Aquino JP, et al The pharmacology of buprenorphine microinduction for opioid use disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2021;41(5):425-436. doi:10.1007/s40261-021-01032-7.

- Wong JSH, et al. Comparing rapid micro-induction and standard induction of buprenorphine/naloxone for treatment of opioid use disorder: protocol for an open-label, parallel-group, superiority, randomized controlled trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13722-021-00220-2.

- Schuster B, et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of buprenorphine in the perioperative setting: A retrospective study. Cureus. 2022;14(3):e23385. doi:10.7759/cureus.23385.

- Fernando RJ, et al. Buprenorphine and cardiac surgery: Navigating the challenges of pain management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(9):3701-8.

- Ward EN, et al. Opioid use disorders: Perioperative management of a special population. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(2):539-47.

- Tsai AC, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002969.