They’ve been called heroes and godsends and walked out of work to applause from passersby. That respect and admiration was a balm to overworked hospitalists. Now many of the nation’s estimated 50,000 hospitalists would gladly pass on the attention and adoration for a return to normalcy.

Normalcy. Remember that? Twelve-hour days? On-off shifts? Using the bathroom without a mask? Two years into the pandemic, the nation’s hospitalists are tired. Many are burned out. Some have left the profession altogether. Others are no longer alive. This is not another story on the emotional wreckage the pandemic has left in hospitalists’ lives. This is the other kind.

Sure, the anxiety and stress remain, but there is also hope. And family. And compassion, and heaping doses of collegiality. To celebrate National Hospitalist Day, we spoke with six hospitalists in different stages of their careers and lives. All have experienced loss these past two years. Yet all can imagine no other calling they’d want to pursue.

Hotels for the healing

Dr. Ajala

Looking back, there was no way Khaalisha Ajala, MD, MBA, FHM, would have ended up anywhere other than where she is today, which is to say a hospitalist and co-director of the division of hospital medicine’s education council at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. And looking back, there’s nowhere else she’d want to be.

Dr. Ajala remembers tagging along with her mother Brenda Austin, a registered nurse, when she went to work. She loved everything about her mom’s job: parking herself at the nurse’s station and taking it all in—the patients passing by in the hallways, the doctors and nurses darting in and out of rooms to help them.

But it wasn’t until later, during her residency, that Dr. Ajala realized she wanted to work in a hospital. “Clinic is important,” she said, “but I really came alive when I was in the hospital.”

Think about it, she said. For a hospital to operate at its best, everyone’s job is critical. “That’s not just the doctors and nurses,” said Dr. Ajala. “The cafeteria lady, environmental services, records, customer service, doctors, nurses—we’ll have to work together to pull it off and we do, every day.”

Dr. Ajala once had another name for hospitals. “Hotels for healing,” she said. “So many people are working to make the patients comfortable. We have to be like a family to pull that off, to keep everyone’s spirits up, and we do it every day. It’s been a miracle, really.”

Escaping to the court

Dr. Alfandre

First came the bed shortages. Then came the staff shortages. The vaccine shortages soon followed. In the hospitals across New York City where David Alfandre, MD, MSPH is a health care ethicist at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Ethics in Health Care and an associate professor of medicine and population health at the NYU School of Medicine, the last two years have been a blur of shortages.

Months fighting a pandemic without end left Dr. Alfandre exhausted and anxious. His self-prescription? A tennis racket.

“Just being outdoors and seeing people in person was the best,” said Dr. Alfandre, who until last summer had never played the sport. “Public tennis courts are great for social distancing, but they’re also great for helping leave work behind. Seeing people and talking to them face-to-face—not on Zoom—is how I cope.”

Dr. Alfandre suspects he’s not alone. Last year, when the nation finally started to gain an upper hand on COVID-19, and family and other visitors were slowly allowed back into hospitals, he remembered what a powerful tool hospitalists and their patients had in friends and family at the bedside.

“I’d forgotten what it’s like having someone who knows the patient in the same room,” he said. “So many people died alone. Now they’ve got someone by their side, and we’ve got someone who can help us with any medical questions or history. Are you kidding me? That’s a gift. That’s like, ‘Happy Birthday!’”

So far in 2022, it’s a gift without any shortages.

Graces abound

Dr. Barrett

Can there be silver linings to a pandemic? If there are, Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, MACP, SFHM hasn’t come across any yet. But graces, the term a friend of Dr. Barrett’s coined? They’re everywhere.

“The pandemic has helped a lot of people see the importance of hospitalists and our profession,” said Dr. Barrett, a hospitalist in Albuquerque, N.M. “There’s been a long-overdue conversation about professional sustainability. I worry about a lot of people—nurses, physicians assistants, doctors. It’s been rough.”

That assessment could apply to Dr. Barrett at times, but she won’t allow it. Every night she texts a friend in Illinois three good things big or small that happened that day. Dr. Barrett’s graces on a recent Wednesday: A nice walk to work … a meaningful palliative-care conversation with a nurse … a lovely walk home from work.

“Sometimes they are deep,” she said. “Sometimes it’s a good cup of coffee.”

Sure, dinner out with her husband or friends helps, too, but the texts “are like a balm,” said Dr. Barrett. “They keep me going.”

A hospitalist at heart

Dr. Bulger

John Bulger, DO, MBA hasn’t practiced medicine in seven years, but the chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan in Danville, Pa. still has a soft spot for hospitalists—even more during this latest wave of the pandemic.

“This might be the most difficult time to be a part of health care in my 25 years, but it’s the hospitalists who are pulling us through,” he said. “Obviously the clinical competencies are important, but the core competencies? The communication with the patients, the families? Helping with the difficult flow of people through care from admissions, to getting better, to post-acute care, to skilled nursing, and eventually getting them home? The hospitalists have gotten us through this.”

And, Dr. Bulger said, they’re the ones who will get us through 2022. “I think the biggest mistake we made in this pandemic was not relabeling it last summer. We need to start preaching that this is an endemic and no longer a pandemic if for no other reason than for people’s mental health.”

With a readily available vaccine and infection rates dropping over the summer, Dr. Bulger said many people saw a light at the end of the tunnel. “Turns out that light was a train coming at us,” he said.

“This is going to be with us for some time,” Dr. Bulger said. “That’s why I’m proud of all the hospitalists who show up every day and never stop doing their job and caring for others. Some days I wish I were right there with them. I guess I’ll always be a hospitalist at heart.”

A support group at home. Work, too.

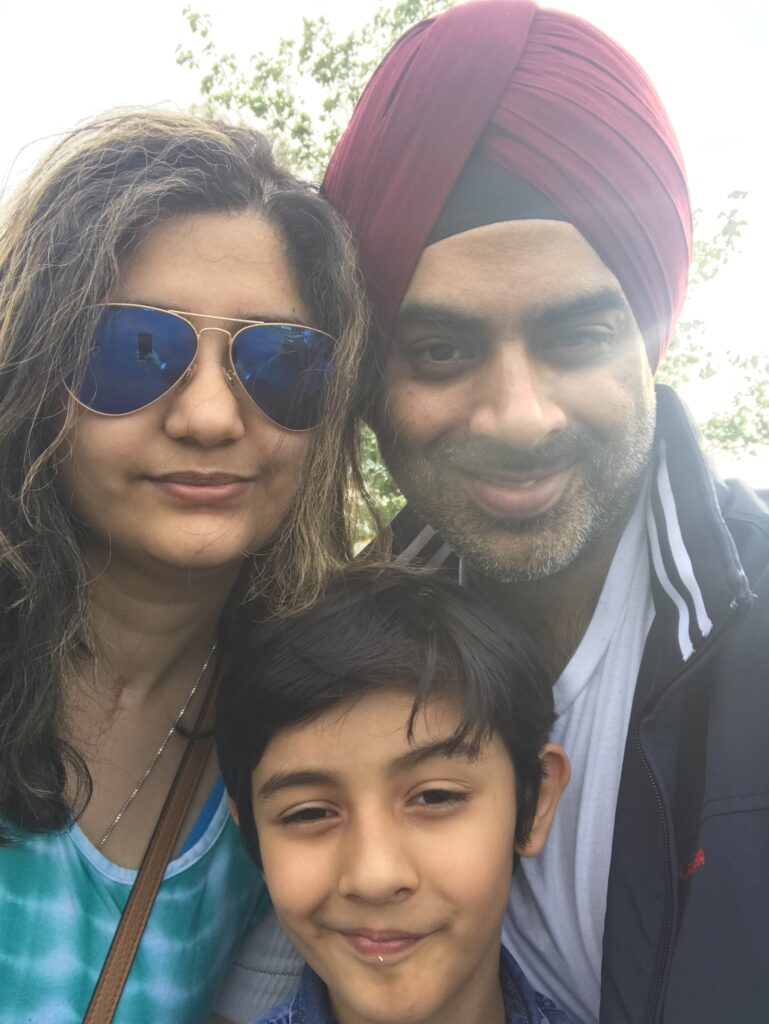

Dr. Gambhir with wife, Ravleen, son, Savir

The hardest part of his job? That’s easy. When the COVID-19 pandemic was at its worst, Harvir Singh Gambhir, MD, FACP, CPL, CPHQ, would pull into his driveway after a long day’s—and frequently night’s—work and not get out of his car. He knew his wife and then-9-year-old son were waiting inside. What he didn’t know was what he might be carrying inside to them.

All he had to go by was an infrared thermometer he used to take his temperature before walking in the front door. “That was my biggest fear,” said Dr. Gambhir, an internist at Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y. “Every night was the same. Every night I worried about what I might bring home to my family.”

The best part of his job? That’s easy, too. Throughout the last year, Dr. Gambhir has been supported emotionally at home, but also professionally at work. Both families have offered heavy doses of whatever he needed that day: advice, empathy, a smile.

“You hear stories, really horrible stories about what other people at hospitals are going through, but it was never that bad for me. I have such a strong team that is there for everyone. Great communication, everyone is willing to help each other. I like to think I’m there for them, too, because their support has made such a difference for me,” he said.

A new beginning

Courtney Edgar-Zarate MD is a mother and an internal medicine/pediatric specialist in Little Rock, Ark. So, it’s safe to say she knows children.

It’s even safe to say she knows her children. It’s also safe to say she knows how the pandemic has affected her work and family. “COVID made me think about what made me happy and what didn’t,” said Dr. Edgar-Zarate. “The past 18 months made me realize I didn’t like my job and what it was doing to my family.”

So she quit.

Well, sort of. Goodbye, Little Rock. The Zarates—Courtney, her physician husband Yuri, and two children—are moving. Hello, Lexington, Ky.

Dr. Edgar-Zarate is going to work part-time at Baptist Health in Lexington. Less money? Absolutely. Less stress? You bet. More time with 10-year-old Leila and 7-year-old Bianca? Most definitely.

Just thinking about that makes Dr. Edgar-Zarate smile, something that’s been missing the past 18 months. Summer’s coming. There are boxes to be packed. “I still get a little tight thinking about it,” she said. “But for our careers, our family, I’m happy. The kids will come around. It’s a new beginning.”

Here’s to new beginnings for Dr. Edgar-Zarate—and all hospitalists.

Robert Bell is a freelance writer in Greensboro, N.C.